A cratered, rusty-red wasteland littered with rocks that’s arid, bitterly cold and devoid of plant life.

That’s an accurate working description of Mars. But also this remote Canadian island, 1,000 miles south of the Earth’s North Pole.

Devon Island is the world’s largest uninhabited island and part of the Canadian High Arctic Archipelago, Nunavut. To the Inuit of Nunavut it is known as Taallujutit Qikiktagna – Jaw Bone Island.

To a small cabal of scientists, it’s Mars on Earth.

For two months during the height of summer when the ground is snow-free, researchers and their associates head to the Haughton-Mars Project Base Camp on the island to conduct research into how human explorers might live and work on other planets. Despite it being summer, temperatures rarely rise higher than eight degrees C with the average annual temperature a bone-biting minus 16 C.

Devon Island (above) is the world’s largest uninhabited island and part of the Canadian High Arctic Archipelago

Scientists use Devon Island – dubbed Mars on Earth – to research how humans might colonise other planets. The epicentre of their work is one of the highest-latitude ‘impact structures’ on Earth: Haughton Crater. Above is a Nasa rover exploring the crater’s other-worldly terrain

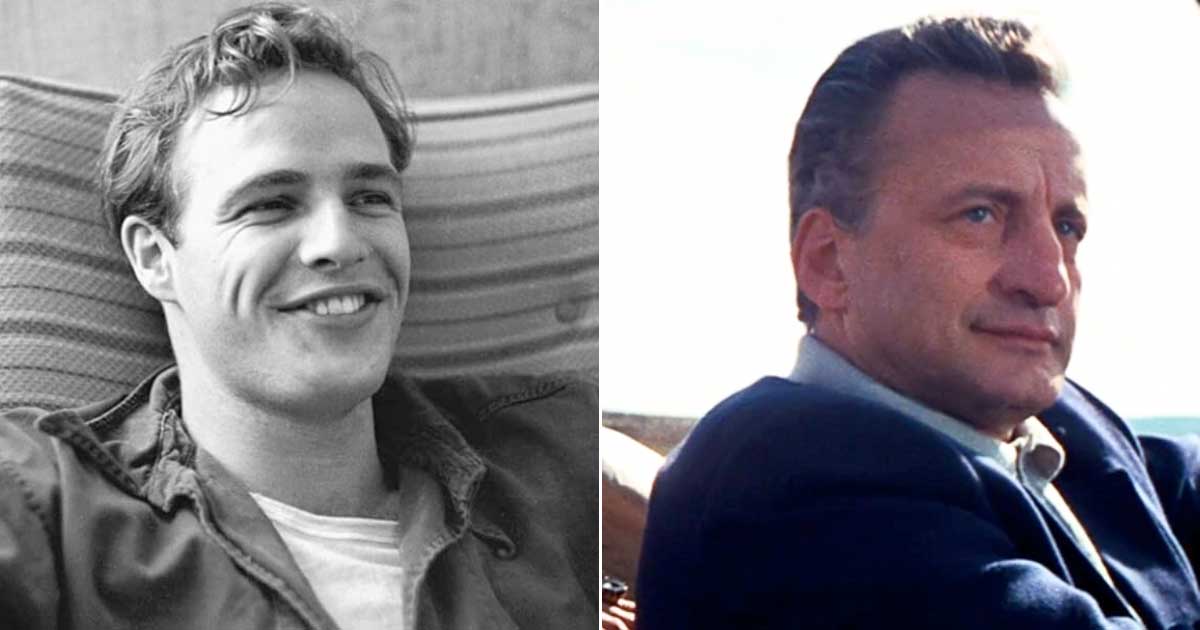

An image acquired by the Nasa Terra satellite on June 28, 2001, showing Devon Island from above

A rover and the Haughton Mars Research Project base camp at Haughton Crater

An aerial shot of the Haughton Impact Crater, which measures 14 miles in diameter

The epicentre of their work is one of the highest-latitude ‘impact structures’ on Earth: Haughton Crater. It was formed around 23million years ago, when an asteroid or comet collided with the planet, and is around 14 miles (22km) wide.

Whatever the projectile was that struck Devon Island, it was about 0.6 miles (one kilometre) in diameter and hurtling at cosmic speeds. It delivered a pulse of energy equivalent to 100million kilotonnes of TNT on collision. The impact obliterated almost all life for several hundred miles around, and flattened the landscape.

After the dust settled, what was left was a smouldering hole, which became the Haughton Crater.

It ripples with canyons, valleys, and gullies. This ‘patterned ground’ is covered in ice that routinely thaws and refreezes.

The ground in the crater has suffered very little erosion due to the lack of rainfall – much like the surface of the Moon.

These factors make the crater an ideal practice ground for emulating an interplanetary expedition.

Recent images from Mars beamed back to Earth by the Perseverance rover in March 2024, show a marked likeness to Devon Island’s lifeless landscape.

Every summer, the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) – a collaboration between Nasa, the Seti Institute, and the Mars Institute – takes advantage of the otherworldly topography to conduct their experiments.

Their base camp sits at the edge of the Haughton Impact Centre. All supplies must be flown in.

Geologists and biologists investigate this ‘polar desert’ (an expanse that is very cold and very dry) – to see how the rocks and microbial life forms may compare to what we know about the Moon, Mars, and other planetary bodies.

Astronautical explorers and engineers develop exploration technologies.

For example, Mars has a thin atmosphere and – as one might expect – no dedicated runways for flight vehicles to land. A thin atmosphere makes it difficult for space craft to get ‘lift’, while rough, rolling geology makes it difficult for them to land.

Consequently, HMP has been working on remote control vertical take-off and landing vehicles (VTOL) – light aircraft that can take off in adverse atmospheres and land on rocky ground. The alien terrain and wicked winds buffeting the crater make it ideal for testing these aircraft.

Other space tech they’ve tested includes robotic rovers, drills, life support systems, plant growth systems, and concept spacesuits.

The latter is particularly crucial.

One of the critical elements that will facilitate humans walking on Mars is a spacesuit designed to deal with its brutal environs: the thin atmosphere is a fug of carbon dioxide, nitrogen and argon gases. Arnold Schwarzenegger asphyxiating when exposed to the planet’s atmosphere at the end of 1990’s Total Recall is surprisingly accurate.

Additionally, the oxidised dust particles that give the planet its characteristic russet hue frequently kick up into violent dust storms.

A spacesuit would have to be able to withstand these violent elements if people were to survive on the surface of Mars. Hence – extensive spacesuit testing at the Haughton Crater.

A researcher conducting a drill in the Haughton Crater, Devon Island. Nasa technicians simulate potential mission emergencies at the desolate location

Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station. The habitat is utilised by scientists and researchers on an ad hoc basis

Devon Island is also home to the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station, which also serves as a Mars analogue. Initiated by the Mars Society, a non-profit volunteer organisation, the habitat is now utilised by scientists and researchers on an ad hoc basis – many of whom work for Nasa or similar international space programs.

Prior research conducted at FMARS includes testing ‘Low Level Laser Light Therapy’ – used to keep astronauts flexible and limber when exposed to cold temperatures for long periods of time. Despite glowing red, Mars is unimaginably cold – minus 60 degrees celsius on average, up to minus 160C at the planet’s polar caps.

FMARS also practices ‘Crew Safety in Simulated Emergency Situations’.

A polar bear hunting narwhal and beluga whales on the coastline of Devon Island

Breathtaking: The northeast coast of Devon Island is an area riddled with glaciers and fjords

From Greenland it is possible to sail to Devon Island following the path of the fabled Northwest Passage

In these, Nasa technicians simulate potential mission emergencies, such as toxic chemical leaks, EVA suit leaks, power failures, habitat depressurisation, habitat fires, power failures, or medical emergencies, to develop contingencies to deal with them.

In a documentary about the Devon Island projects called ‘Passage to Mars’, the scientists noted that if their experiences on the island are anything to go by, ‘only the most rugged explorers will thrive on the Red Planet’.

Can I visit?

Tourists do venture to Devon Island.

From Greenland it is possible to sail there following the path of the fabled Northwest Passage, a trek many a European explorer took in the 19th century in the hopes of finding a direct route to mainland China (they failed).

However, rather than heading to the crater, travellers tend to head to the Truelove Lowlands area, on the northeast coast, an area riddled with glaciers and fjords, breathtaking icy landscapes that are quite unlike Mars.

Comparatively warm (two to eight degrees Celsius in summer), with some vegetation, this area sees grazing musk-oxen, waterfowl and roaming lemmings.

In the coastal seas surrounding the island, you can spy narwhal and beluga whales.

It’s not Life On Mars, but these magnificent creatures are other-worldly in their own right.