Denver sound artist Jim Green, whose best-known public art includes a playful installation under a block of Denver’s Curtis Street and the train calls at Denver International Airport, died on Wednesday in Florida at age 75.

Green was a prolific and highly collaborative artist, friends and colleagues said, pushing the boundaries of art with playful, subversive pieces that surprised and delighted anyone who encountered them.

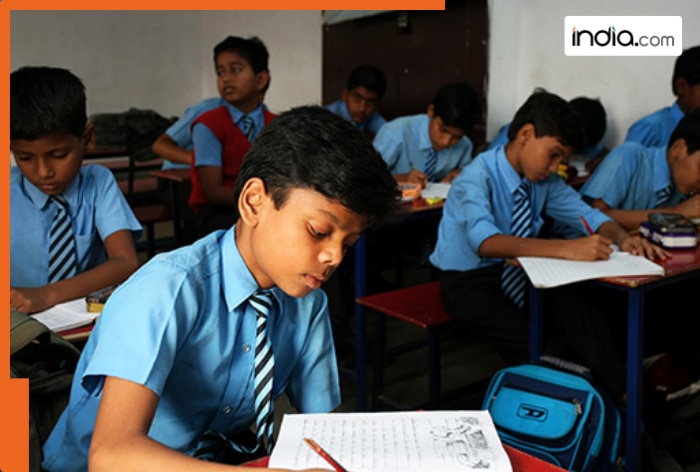

Hyoung Chang, The Denver Post

Travelers who ride the train at Denver International Airport — and that’s most of them — have for decades heard artist Jim Green’s work “Train Call,” which features playful sounds and recognizable voices. Pictured here on Sept. 29, 2020.

“It’s a big loss for the art world, and personally,” said Rudi Cerri, program manager with Denver Arts & Venues, which curates the city’s public art collection. “His ‘Soundwalk’ piece on Curtis Street is probably my favorite piece in the entire collection.”

“Soundwalk,” which was installed in 1992, consists of speakers hidden under a half dozen metal grates along the sidewalk in the 1500 block of Curtis. It plays anywhere between 40 and 100 sound clips per hour, ranging from rumbling and gurgling water to farm animals, motorcycles and trains. It’s become such a downtown fixture over the decades that it’s had to be upgraded from cassette to MiniDisc and now, a hard drive containing the sounds. Cerri expects it will be there another 50 years or so.

“Green was probably the first to record creative messages for public transportation, including the greetings on the train at Denver International Airport, rapid transit in Salt Lake City, and in Fort Collins,” said friend and veteran public art curator Kathryn Charles. “Jim instructed us to ‘Hold on, the train is departing’ using the voices of Alan Roach, Reynelda Muse, Peyton Manning, and Lindsey Vonn. His chimes between messages were homemade from various plumbing pipes, and early synthesizers.”

That piece, entitled “Train Call,” has been heard by tens of millions of people over the years — even if many may not have realized it was a public artwork.

“He has a piece in the Colorado Convention Center called ‘Laughing Escalator’ and it’s always startling to hear at first as you’re going down it,” Cerri said. “He always had a knack for making his work funny but also with a little edge to it, like the laughter is slightly mocking you. … It takes you out of thinking about the airport or your convention or whatever and puts you in the moment.”

Even with an edge, Green was practically the “Mr. Rogers of the art world,” Charles said, with a pacifist outlook on life and a love of long conversations over tea. In his life and in his work, he prompted big and unexpected reactions from the public, and relished talking with people about how it made them feel.

Green also created the sounds and, often, the technology that underpinned talking vestibules and kiosks in public spaces across the country, including one at City Park near the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial. His ‘Talking Trash Cans’ in front of the Arvada Center welcomed visitors with greetings of positive affirmation, including “I like your shoes” and “You look great today!,” according to Charles.

“‘The Red Phone,’ installed at Redline (Contemporary Art Center), made a direct connection with Green who was willing to talk to his audience one at a time, live,” said Charles, adding that she’d never before heard of an artist connecting a public artwork directly to his cell phone.

Green, born in Minneapolis in 1948, obtained his master’s degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and lived in Denver until about a decade ago, when he was moved to Florida to be closer to his sister for medical care, she said. He was “a keen observer of human nature peculiarity,” Charles wrote in a statement provided to The Denver Post. “His early recordings and research lead him to travel the country one summer to document the sounds of amusement parks and state fairs. He amassed a catalog of recordings of people working in sideshows, their shticks, and their stories.”

“When he tried out for choir in school they told him he was a better listener than singer,” Charles said with a chuckle. “That might have been his biggest strength.”

“I take what’s in the environment already and change it just a little,” he told The Denver Post in 2005. “It breaks down some of the feelings of separation in public spaces.”

Green’s death was confirmed to The Denver Post by his sister, Mary Strouse. He had no spouse or children. He had been diagnosed with posterior cortical atrophy, a syndrome that causes brain cells to die over time.

Get more Colorado news by signing up for our daily Your Morning Dozen email newsletter.