Three years later Hulls threw herself into researching Chinese history, interviewing family members, learning Mandarin and travelling to Hong Kong and Shanghai to retrace her grandmother and mother’s steps.

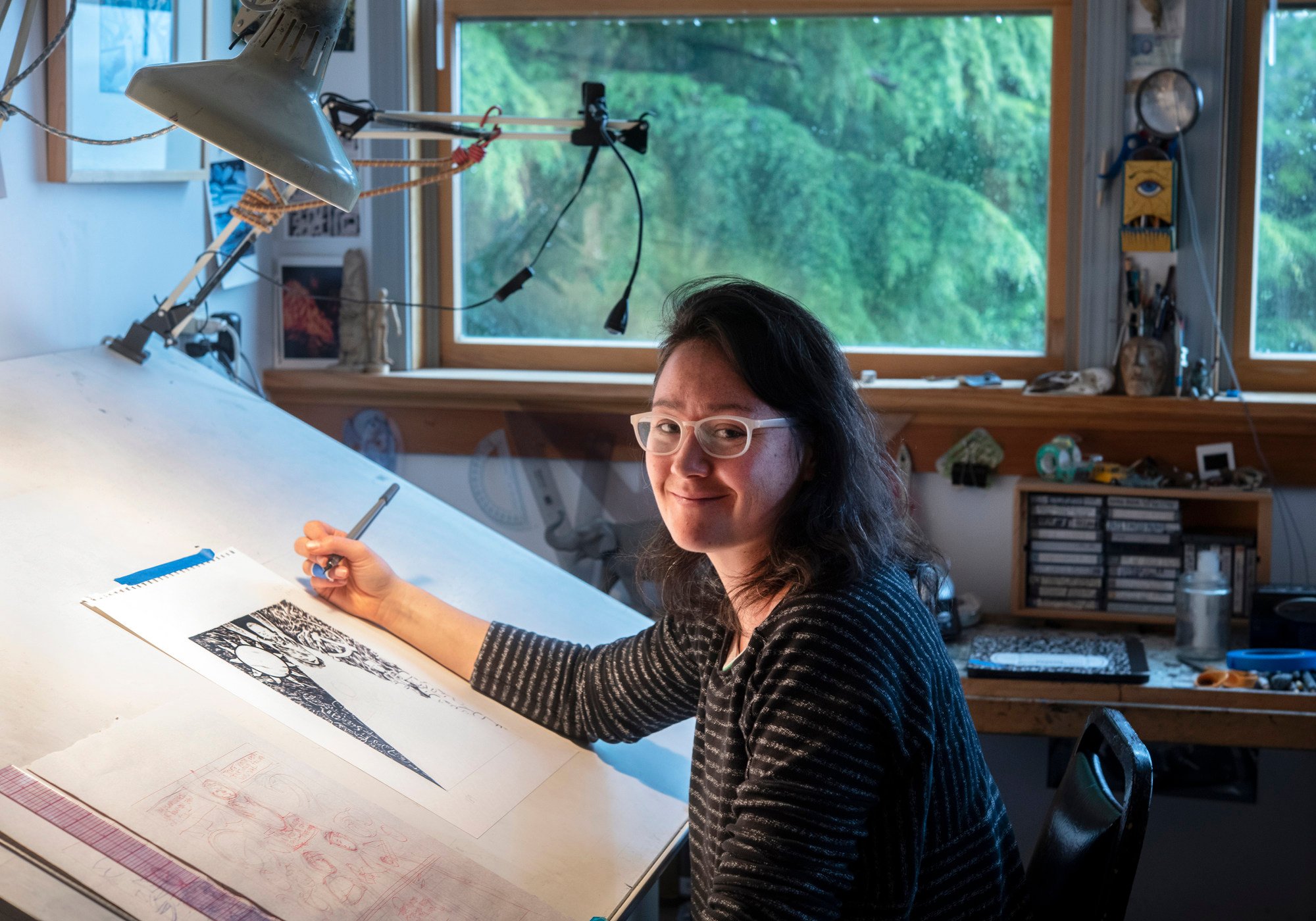

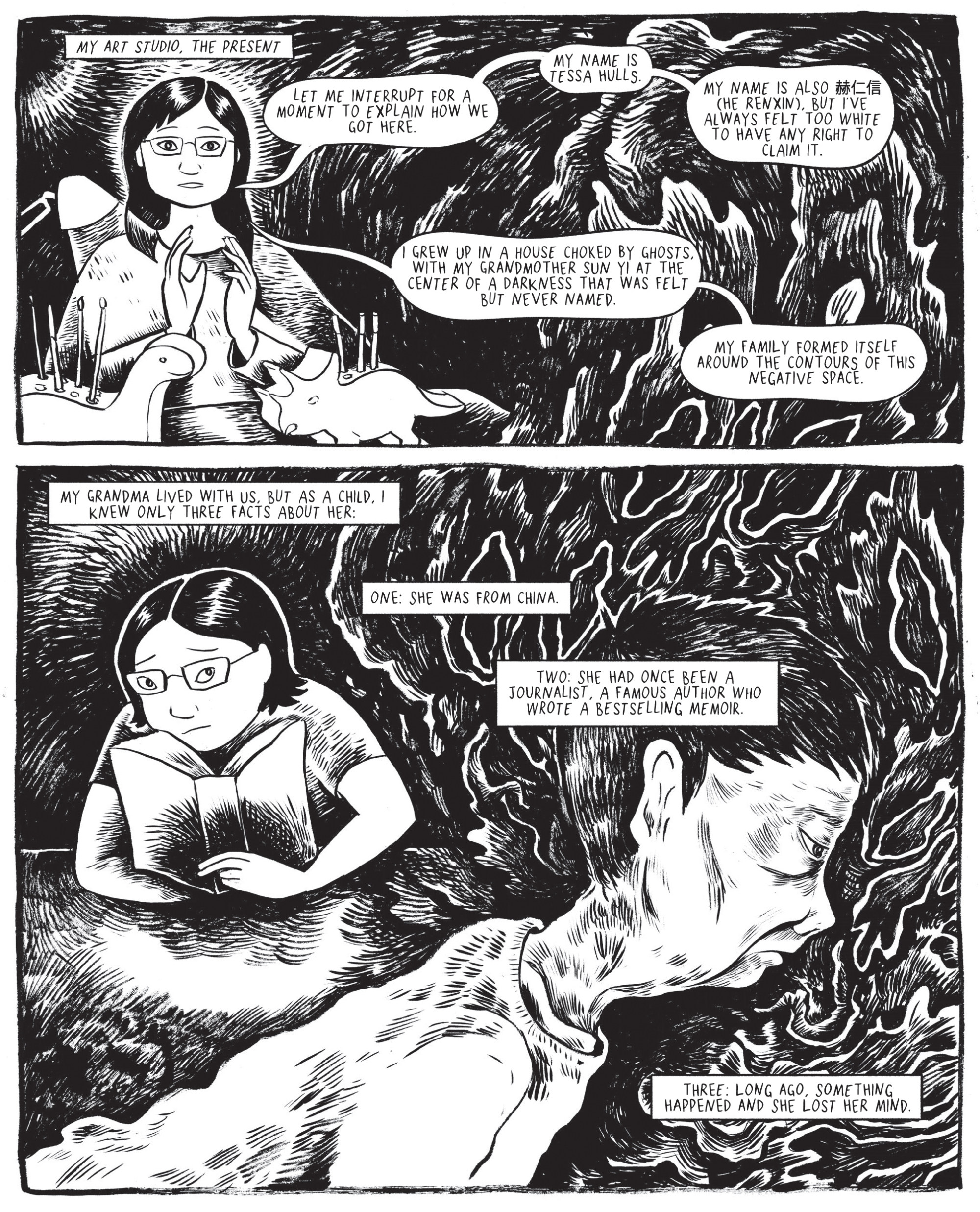

Hulls’ first graphic memoir, Feeding Ghosts, the fruit of seven years’ work, was published by Macmillan this March. It is raw, intense and honest.

Drawing and writing out stories of intergenerational trauma from 1920s China to 1950s Hong Kong, to the present-day United States gave Hulls a much more nuanced understanding not only of her grandmother and mother, but also herself.

“The epic scale is definitely something that people are commenting on, and the way in which it braids a lot of very complicated threads,” says Hulls, 39.

“The fact that people are recognising the complexity and the relationship between the microcosm of my family and the broader Chinese and Hong Kong history, it’s making me feel like I did what I set out to do.”

The mysterious Chinese beauty caught smuggling drugs to the US

The mysterious Chinese beauty caught smuggling drugs to the US

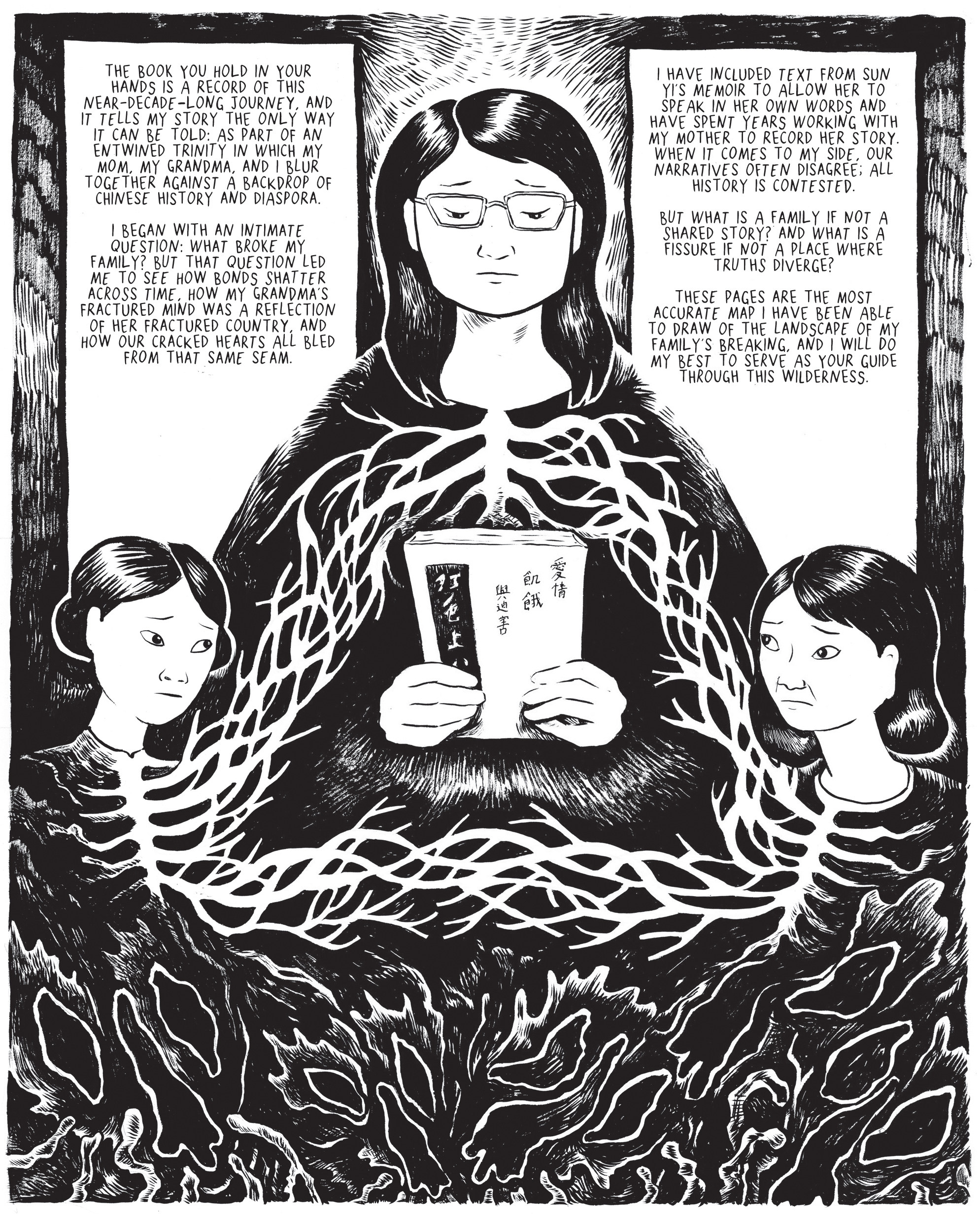

She presents the lives of Sun and Rose in their own voices as much as possible, while Hulls, one-quarter Chinese, tries to figure out not only her family story but also how modern Chinese history played a role in shaping her grandmother’s and mother’s lives.

What she could not put into words Hulls put into black-and-white drawings – at times detailed sketches such as the serenity of a Chinese garden in Suzhou or an amusing sketch of an Airbnb room in Shanghai where a toilet and shower are cordoned off by a clear shower curtain. Others show Hulls depicting herself talking directly to the reader.

For her, the graphic novel format was the best way to present the multi-generational story in its various layers.

“If I had done it as a written book, it probably still would have been 400 pages, but it would have been so dense and unapproachable,” she says. “I knew that by adding the imagery, that was the way that I would be able to temper the weight of the history and offer viewers a way in.”

Feeding Ghosts is divided into nine sections, three for each woman’s generation, interspersed with present-day reflections.

It starts with Sun, who worked for a Nationalist newspaper in Shanghai in the late 1940s. As the Communists approached the city, many fled to Taiwan, Hong Kong or further, but Sun stayed behind, naive but determined to report on history unfolding.

Her life was further complicated by a dalliance with a Swiss diplomat, which resulted in the birth of Rose, Hulls’ mother, in 1950. Through her research, Hulls was able to discover more about her grandfather, and she includes this unexpected information in her book.

For her relationship with the diplomat and her criticisms of the Communists, Sun was politically persecuted for seven years, detained for days at a time and forced to undergo thought reform by writing numerous “confessions”.

Through making this book, I really understood that both my mom and my grandma had really valid things to fear

Tessa Hulls

In 1957, Sun and Rose escaped Shanghai and fled to Hong Kong by boat.

Arriving in the then British colony should have been a relief from the relentless Communist re-education but instead it was the beginning of Sun’s mental breakdown, which led to Rose living a dual life, managing her mother’s mental illness while navigating her own young life.

For Hulls, being in Hong Kong and mainland China for the first time was a revelation in understanding her mother and grandmother.

“I feel like my time in Hong Kong on that first trip I was just starting to grasp how much larger the story would have to be.”

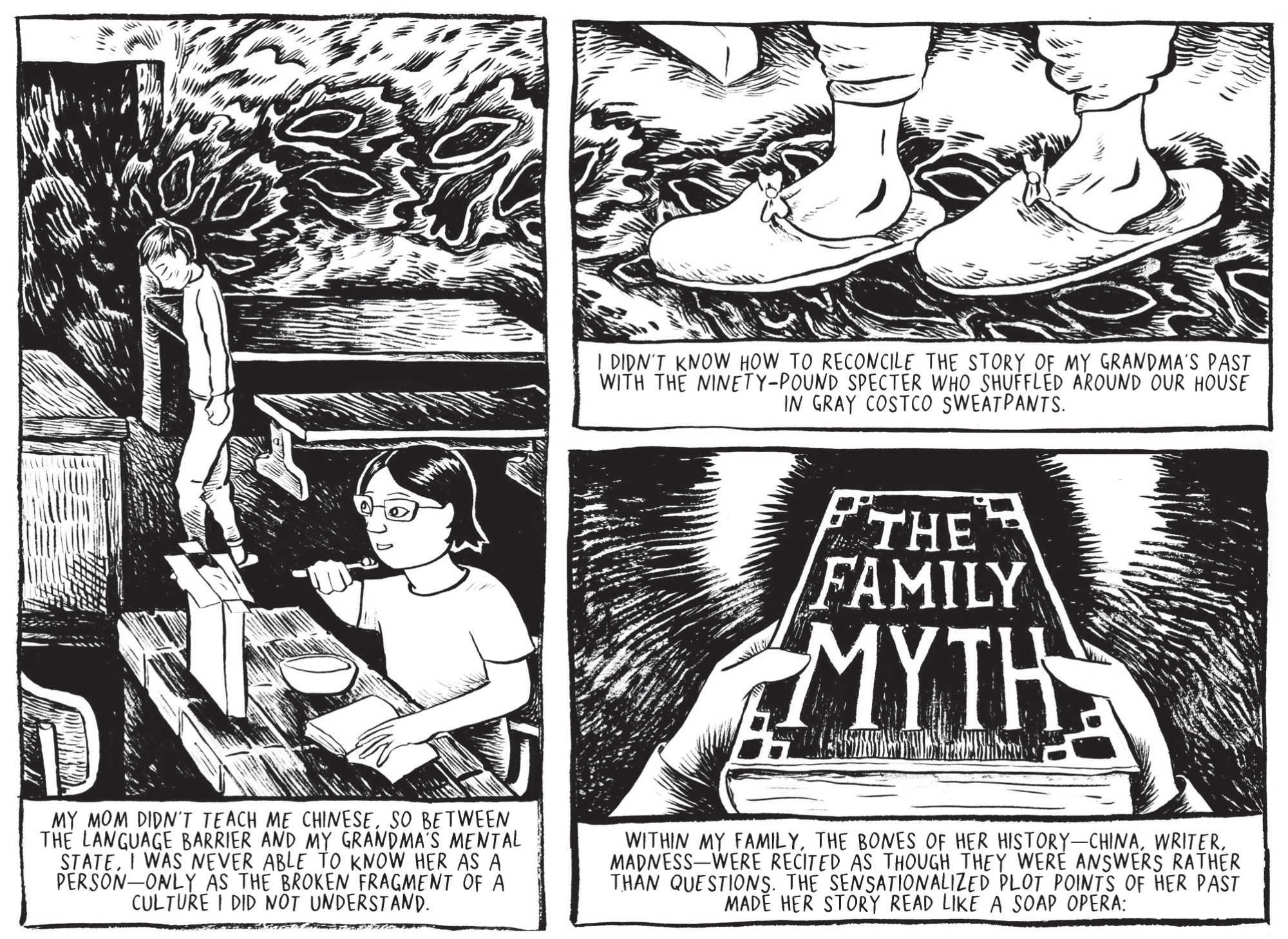

With mother and daughter having escaped the Communist revolution, people outside China clamoured for information about life behind the bamboo curtain, and Sun’s 1958 memoir, Eight Years in Red Shanghai: Love, Starvation, Persecution, became an instant bestseller, which gave her the financial means to enrol Rose in the prestigious Diocesan Girls’ School (DGS), in Jordan, Kowloon.

“I did not appreciate just how British my mother’s upbringing was until seeing DGS,” says Hulls. “It completely blew my mind. And I was like, ‘OK, I’m going to have to have a very good long think about this,’ because this casts so much of my understanding of my family, childhood and culture in such a different light.”

In particular, her mother growing up in Hong Kong enlightened Hulls about the city’s unique East-meets-West culture.

“I think my mom, being Eurasian, she flip-flops so easily between talking about Chinese culture and British culture,” says Hulls. “When she wanted to make a point that was Chinese, then she would speak from this fully Chinese place. And then when she wanted to make a point that was British, she would speak from this fully British place.

“I really did not understand the complexities of what it had meant for my mother to essentially be raised as an orphan by a colonial boarding school.”

Hulls points out in the book that Eurasians had their place in Hong Kong society, devoting several pages to the history of Eurasians in the city, and that Diocesan Girls’ School started as an Eurasian orphanage and school before becoming one of the city’s elite educational institutions.

While Hulls visited the school and met some of her mother’s classmates, she also went to Castle Peak Hospital, where Sun was admitted after her mental breakdown following the publication of her memoir.

In an exhibition at the psychiatric institution, Hulls was able to see various versions of straitjackets, electroshock machines and insulin shock therapy to induce comas, which could have been used on her grandmother.

A lot of people who go through their parents having dementia wish that they had done more to try and record the stories when they were still there

Tessa Hulls

Although mental illness was a taboo subject at the time, Hulls says Sun was far from the only mainland Chinese refugee to have suffered a mental breakdown.

“With my grandmother there [in Castle Peak], it was pretty much out of sight, out of mind. You just put them away, you don’t talk about it,” she says. “There’s no discussion of the fact that so much of Hong Kong’s population were traumatised refugees.

“That’s where everyone went, after all of these big things happened on the mainland [the Sino-Japanese war, Chinese Revolution, Great Leap Forward], you would get these mass influxes of tens or hundreds of thousands of people. And then no one would talk about the fact that they’re carrying all of these really heavy experiences into this place that now is completely overburdened, trying to care for their physical needs while ignoring that they’re bringing psychological needs in, too.

“That’s the thing for my mom, because she was so profoundly isolated, she really didn’t understand the necessity of human ties on a lot of different levels,” she says.

“After I was in Hong Kong with her, we went to DGS together. I talked to some of her old classmates, then I started really understanding what her life was like. It made so much more sense to me that, of course she didn’t understand human connection, because it was something that she’d never really had access to.”

These issues set the tone for the latter sections of Feeding Ghosts, as a young Rose goes to the US in 1970, eventually marries and gives birth to Hulls and her older brother, and brings Sun to northern California.

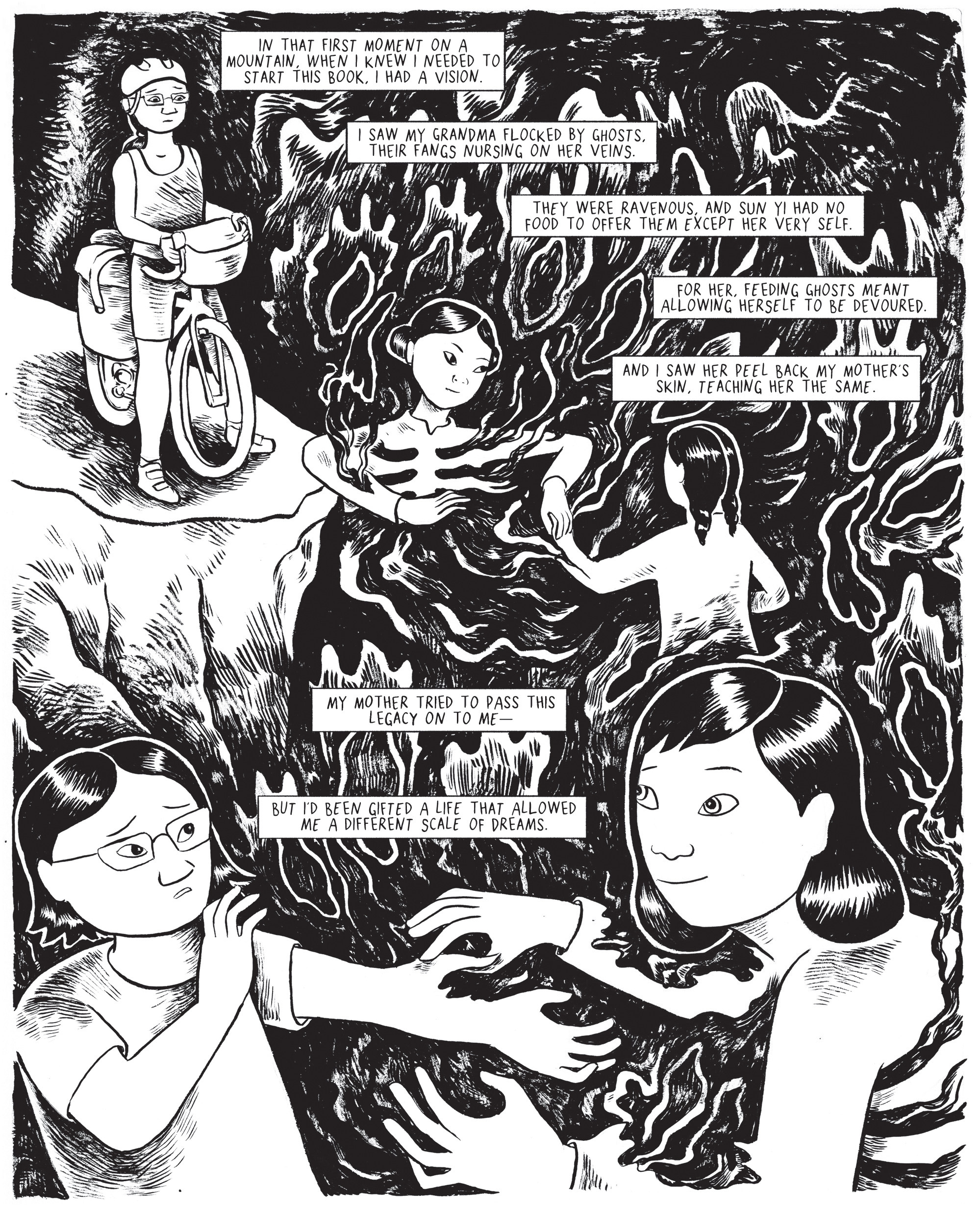

The author recounts growing up and trying to figure out her identity, having had little exposure to Chinese culture. It was when she was in her thirties that Hulls became determined to understand her grandmother’s life in Shanghai by reading up on Chinese history and learning Mandarin to write her memoir.

She takes readers who may not know anything about Chinese culture and history with her on her journey of discovery, interspersing quotes from books such as The Rape of Nanking (1991) by Iris Chang, Frank Dikotter’s The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957 (2013) and Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine (2008) by Yang Jisheng.

“I had to sort of lead with my own ignorance because I’m not an authority on these things,” says Hulls, “and I think it’s kind of a more realistic or honest approach to say that when somebody is diving into history, we’re always choosing one particular thread.

“And I think it’s better to just acknowledge that we’re speaking from a really specific perspective.”

After she had her grandmother’s memoir translated, Hulls was able to extract information on places Sun went, including the address in Shanghai where she rented a room, and discovered the home, in the French Concession, was still standing.

Not only that, but when Hulls and Rose knocked on the door, the occupant remembered Sun had lived there with a child.

“I found myself thinking, ‘Wow, my grandmother is a very heavy-handed ghost,’” says Hulls. “Like, she really wants the dots of the story to connect because I never expected to be able to find that house and then to be invited inside.”

Once they entered, Hulls watched her mother intently and felt it was like being in a time machine.

“I watched all of her emotional walls break down, and she’s somebody who’s so fiercely composed and so tightly held,” says Hulls. “And when we stepped into that house, it was like all of those complex webs that she maintains, she couldn’t do it within that space, because it just brought her back to the reality of this having been the last place she was allowed to be a child.”

In her own childhood, Hulls began demonstrating artistic and literary tendencies, finding refuge in reading and drawing, but her mother was terrified Hulls would follow the same fate as Sun and develop a mental illness from her creative ability.

Rose’s immediate reflex was to become an overprotective mother, which caused Hulls to rebel, leave the city behind and live like a cowboy, a vivid freedom motif that runs through the memoir.

“I understand it, and that’s kind of the full circle place that I arrived at,” says Hulls. “Through making this book, I really understood that both my mom and my grandma had really valid things to fear, and understanding where that began was really what allowed me to have compassion and sort of see why things went the way that they did.

“With some of the more emotional sections of the book, there were pages that did spark really hard and fruitful conversations between me and my mom, allowing both of us to talk about things in our past that had really been painful.”

Despite their reconciliation, history is repeating itself – during the book editing process, Rose was diagnosed with dementia.

“She’s read a lot of the book but she’s never sat down and read it continuously,” says Hulls. “She wants to read it but I’m apprehensive because, obviously, it’s something where there’s a lot of complex threads.

“And I think if you look at the big picture, you can see that there’s a lot of compassion, and I’m telling it from a place of love. But if you can’t keep your eye on the prize, there’s a lot of places where it could be painful if she can’t track what’s going on.”

Hulls says many of her friends are in the same predicament with their parents and so she does not feel alone.

“A lot of people who go through their parents having dementia wish that they had done more to try and record the stories when they were still there,” she says. “I will have no regrets about not having tried to write down my mother’s story.

“So in a way, it feels like this book is a testament to having done everything we could to understand one another while that was still possible.”