“The problem of officials acting arbitrarily or lacking the willingness, courage or ability to deliver must be addressed … We will improve reform incentives and better guide public opinion … to foster a favourable environment for reform,” the resolution read.

Interviews with civil servants have revealed a widespread fear of making mistakes in their work and a lack of flexibility, worsened by tightening oversight by the party’s formidable disciplinary bodies.

Experts also argue that further centralisation and micromanagement stifle innovation and creativity, resulting in a prevailing atmosphere of passivity and conformity.

They say it ultimately undermines the very objectives the leadership seeks to promote: for officials to get things done.

“Since the anti-corruption campaign kicked off in 2013, the stick has grown much larger, and the carrot hasn’t changed, so naturally we see less innovation and experimentation,” said David Janoff Bulman, an assistant professor of China studies and international affairs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Tighter control, fewer risks

As the central government has tightened its grip, many civil servants appear less likely to take risks and are more inclined to wait only for explicit instructions, observers say.

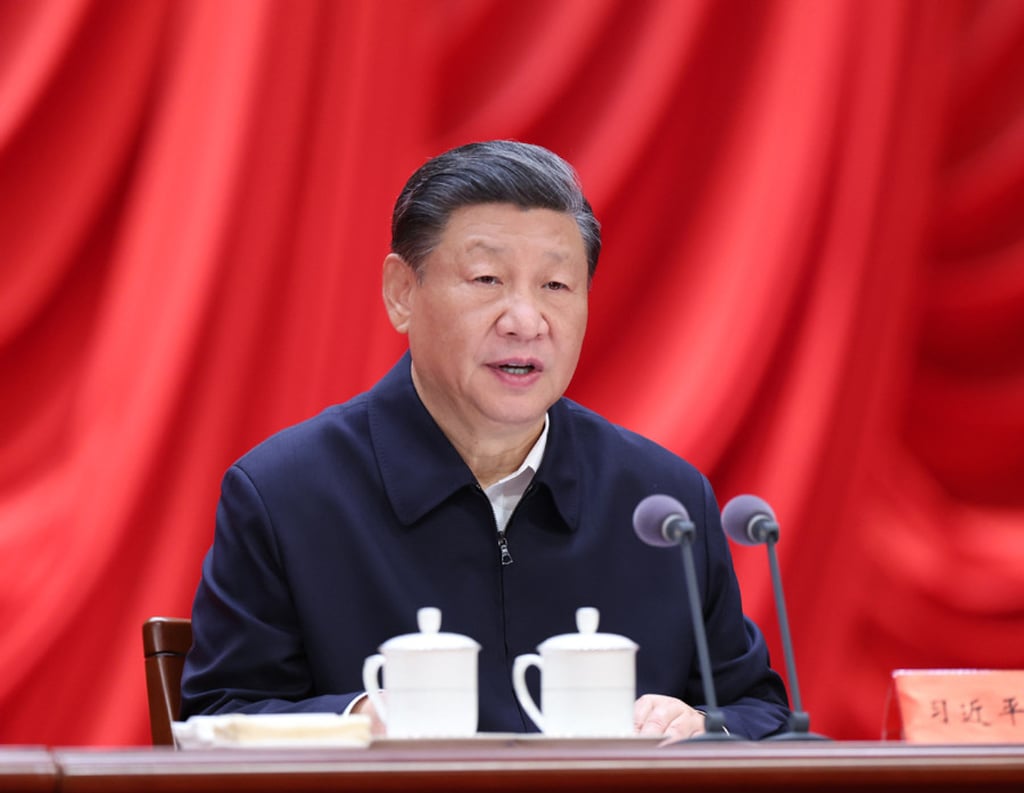

In the past five years, nearly every major policy announcement – ranging from the national security law in Hong Kong, China’s Covid-19 response and its post-pandemic economic recovery – has been described by Beijing as being the result of Xi’s “personal leadership”.

“This shift towards micromanagement limits the operational space of local officials, resulting in the rise of ‘lying flat’ cadres,” said Shan Wei, a senior fellow on Chinese politics at the National University of Singapore.

“Xi seeks a cohesive system united in heart and mind, where officials strictly follow his directives, just as the brain controls the arms.”

Experts say officials have also been deterred from pursuing innovative policies because of Xi’s extensive anti-corruption drive, which has brought down numerous high-profile figures in campaigns such as the “accountability review of 20 years” that delved back two decades for signs of wrongdoing.

By September 2022, the campaign had investigated 789 cases involving 1,163 people, according to Inner Mongolia’s commission for disciplinary inspection. Some 942 people were disciplined.

Bruce J. Dickson, professor of political science and international affairs from George Washington University, said: “Rather than risk making a mistake and be investigated [by the CCDI] – for instance by seeking new foreign investment or offering greater support to the private sector relative to [state-owned enterprises], both of which were rewarded with promotions in the past but often tainted by bribes and illegal land grabs – local officials seem more likely to play it safe.”

Adjusted measures

Early in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, leaders in Beijing acknowledged it was not sustainable to punish all officials who had done something wrong with the same harsh measures.

Graft fighters have since sought to differentiate the wrongdoings of officials and issue a proportional response after senior officials were demoted or even resigned after being found to have transgressed.

In one high-profile example in the past year, former foreign minister Qin Gang lost all his official titles with his resignation but did not receive further punitive action, and there has been no official announcement of a probe regarding him.

Similar measures were reinstated in last month’s third plenum as Beijing seeks to reduce punishment and inspire vigour among officials.

“We will apply the ‘three distinctions’ to encourage officials to forge ahead in a pioneering spirit and demonstrate enterprise in their work,” the post-plenum readout said.

The “three distinctions” is Beijing’s push to differentiate between errors due to inexperience, particularly in new projects, and intentional rule violations for personal gain.

The resolution said the party would better exercise “four forms” of discipline inspection, which classify punitive measures by severity, ranging from criticism and light penalties to heavy penalties and prosecution.

In recent years, graft fighters have already tried to lighten punishment and publicised instances they consider to be good demonstrations of leniency to wrongdoers.

In Hubei province in central China, two officials faced scrutiny in 2018 for bypassing procurement procedures because of urgent circumstances.

In one of the instances, an official from a river management bureau expedited dam repairs before the flood season, prioritising public safety without personal gain, according to articles published by Hubei’s provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection.

Similarly, a district government official initiated a local infrastructure project using a lottery to select contractors instead of proper bidding, motivated by the need to accelerate the project for the benefit of the community, the disciplinary committee said.

Despite not adhering to regulations, both decisions were collectively supported and justified as necessary actions.

In Huaiji county in southern Guangdong province, the discipline inspection commission has established a follow-up education programme for officials who have been disciplined.

From 2022 to October 2023, some 13 out of 168 tracked individuals received promotions after showing good performance post-discipline.

The adjusted punitive measures “indeed suggested that a more relaxed atmosphere can diminish the sense of risk”, said Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago.

But some officials might feel that minor penalties remained significant enough to curb their ambitions, he warned.

“For example, for a competent official who desires to obtain a vice-ministerial position … a minor reduction in punishment isn’t enough to make it worthwhile [to innovate and make mistakes], as he may feel that such a penalty still poses serious consequences, albeit slightly less severe than before.”

Two public servants from the southern city of Guangzhou interviewed by the South China Morning Post echoed the view, saying the effects of the “three distinctions” and “four forms” were barely felt.

One official from the Guangzhou Municipal Commission of Planning and Natural Resources said she hoped more detailed measures would roll out, because “nowadays the competition is fierce, everyone is afraid of taking responsibility” and no one dares make any bold moves.

Fewer carrots

Bulman argued that the party must change how cadres are managed to incentivise them.

“To really create a new generation of innovative and bold county leaders, the party would really need to change the cadre management system to allow new incentives (monetary or downward-accountability based),” he said. “Simply telling cadres to be bold is not going to cut it.”

He added that current promotion reasoning was not quite adequate.

The “central control” logic involving appointing provincial officials after local leaders were ousted for corruption created a risk-averse atmosphere, he said.

And the “career development” logic under Xi emphasised promoting officials with diverse experiences, leading to frequent short-term appointments that discouraged innovation in favour of avoiding failure, he said.

Lastly, the “development or diffusion” logic pertains to officials who demonstrate capability in one area and are then moved to implement reforms or new policies elsewhere.

“These correspond to the third plenum language goals, but the frequency of this type of rotation is more in doubt,” he said.

Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said an effective incentive pay system could only work when: first, the task is clearly defined; second, the employee’s output is measurable; and third, the result could be directly linked to an employee’s input.

In China, however, “many tasks for the civil servants are not clearly defined,” he said.

Wu said that theoretically, civil servants should have their own job description and simply focus on their own responsibilities, but during Xi’s tenure, there was an increasing number of top-down directives – to the extent of being alarming.

“He tends to assign tasks, and expects everyone to carry them out. But these tasks are not clearly defined. Additionally, getting too many tasks has made it difficult for the staff to understand which tasks are actually important.”

Shan Wei pointed to the example of Chongqing under Chen Miner who was party chief there from 2017 to 2022, where officials were told the improvement of the business environment was “Project No 1”.

Shan observed significant enhancements in the attitude and efficiency of local government service windows handling public affairs. The party chief held officials accountable for inadequate citizen assistance and mobilised resources to support the initiative, leading to marked improvements in service quality.

Slow growth

Financial constraints have also prevented officials from pursuing new initiatives, observers say.

In southeastern Fujian, the education bureau in Changting county aims to “resolutely eliminate” the “personal use of public resources” – such as using office supplies to print test papers for employees’ children.

Victor Shih, a specialist in Chinese elite politics and finance at the University of California San Diego, said: “Most local governments today don’t have a lot of money due to debt. So if local officials want to launch an initiative, they will need to collaborate with private entrepreneurs. However, given the intensity of the anti-corruption drive, most will hesitate.”

Yang said existing strict guidelines to cut back extravagance might limit innovation, especially in less developed regions where local government funding had become constrained.

Vague incentives

But, like everything else in China’s massive state system, the rewards are pretty-much determined by one’s level, and the lower rank civil servants were not likely to receive high honours, she said.

With the incentive mechanism in place, those who work harder and do better should get better performance evaluation said Gloria, who is in her late 20s and requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue.

But she found the criteria were often vague, and her fellow cadres’ performance largely depended on the supervisors’ judgment.

Despite receiving a bonus of 1,500 yuan (US$210) amid a heavy workload and long hours, Gloria said, “there are no extra pay incentives for overtime, and I feel my work is underappreciated”.

Her performance is assessed based on services for foreign personnel and enterprises, such as explaining consular protection knowledge and Apec business travel cards.

“The mechanism is somewhat effective, but in practice it depends on the leader’s selection and employment criteria,” she said. “There is no quantitative standard, and there probably won’t be one, as it’s difficult to quantify.”