What he dreamed of was a simple, casual place that would break down the haute cuisine dessert experience and make it accessible for all. At the time he had no idea how difficult that would prove to be.

Getting Coda, which he opened in 2016 in Berlin’s now-trendy Neukölln district, to the point of success it is now at took much trial and error – plus, ironically, a Michelin star, with many of the fine-dining trappings that tend to go with one.

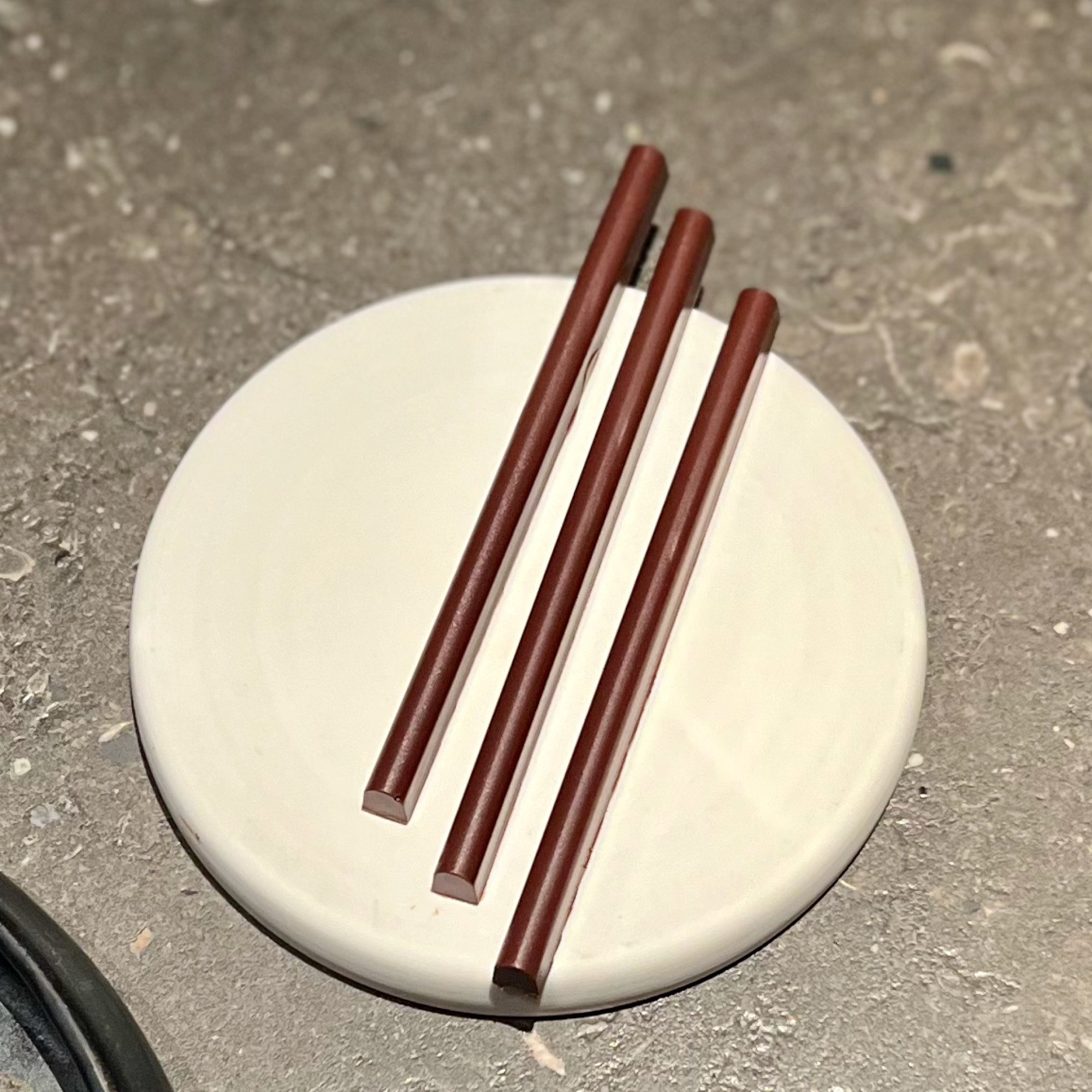

He serves a fine-dining dinner menu of 15 courses that may include a gummy bear made of dehydrated red and yellow beet, or a squiggly strip of beechwood-smoked and caramelised crispy pork skin that has been rolled in dried sauerkraut powder and topped with blobs of pear purée and Sicilian pine nuts.

Coda, meaning “finale” or “concluding remark”, explores what happens when the conclusion to dinner becomes the meal. It is not a dessert bar – this is one of the descriptions that Frank threw out.

Only two or three of his dishes would be considered dessert at a traditional Western restaurant. He applies pastry techniques to savoury ingredients, and gives sweetness a dash of salt; almost all of his dishes have noticeable umami elements.

While French tradition dictates that savoury courses come first, sweets at the end, Frank – who has done stints at three-Michelin-star Georges Blanc in Vonnas, France, and Akelarre in San Sebastian, Spain, as well as Nihonryori RyuGin in Tokyo and Kikunoi in Kyoto, Japan – looks primarily to Asia to see how sweet and savoury can work together both in individual dishes and through a multi-course menu.

“Dessert has to be seen in context. Traditional French food has no sweet components – maybe with foie gras there’s a sweet fruit accompaniment – but otherwise it’s savoury,” he says as we bite into a Gouda-stuffed brioche made of rice flour and drizzled with turnip caramel at Coda.

“But influence from Asia, and to a lesser extent South America and perhaps countries such as Spain, where, say, a starter is as sweet as a dessert, or fruits are used throughout the menu, means that dessert can’t be too sweet or it would be overpowering.”

While he turns French menu tradition back to front, he respects culinary convention when it comes to complexity – although giving it his trademark unexpected twist.

Recognising that savoury dishes have the potential for greater depth and layers of flavour, he borrows an approach from grande cuisine kitchens: Frank swaps the saucier station, which reigns supreme in classic cooking, with his bar – seven of the 15 dishes are served with an accompanying beverage, with or without alcohol.

When Coda first opened, Frank offered à la carte alongside two-course, three-course and five-course menus. This attracted a variety of diners, including those who “shared one dessert, had a glass of tap water and stayed for two hours”, and those who combined three-course and five-course menus to each have eight courses.

It was successful, but too difficult to plan ahead with what would be required each night.

He changed the format to two sittings: 6pm, when he served six courses, and 10pm, when diners could order à la carte or three- or four-course menus.

The first sitting was unpopular – “no one could understand that they must now eat six courses, and we even had a reservation for six people who ordered only one set and had one dish each,” he says.

Berlin, city of night owls, ensured the second sitting was packed, but unfortunately this still did not equate to success. Frank had promoted Coda as a place for dessert, so diners would go for a lavish dinner elsewhere and only “come to ours full and drunk”.

He realised he needed to communicate that Coda equals dinner. He also needed somebody else to put Coda in a category that diners could understand – after two years of experimentation, he realised he needed the Michelin magic.

“I didn’t want to change our concept or change our food, but I did want to make it work. I decided to offer just set menus, and realised I needed a star,” he says.

He brought in proper napkins and a more comprehensive wine menu. But he knew that what Michelin truly values is consistency and quality of produce.

Few pastry kitchens are known for using top-quality, natural ingredients, even in three-Michelin-star establishments, he says. Industrially processed chocolate, frozen fruit purées, chemical food colouring, stabilisers and highly processed white sugar remain common.

For cooking, haute cuisine requires high-quality dairy products but pastry kitchens regularly use UHT cream to get a consistent result.

Frank thus banned refined white sugar, extracting sweetness instead from ingredients such as corn, beetroot, carrots and fermented rice, and upped his use of organic and sustainable products.

“We took the same approach as in regular kitchens – if you cook potatoes, you go to the farmer to find the best potato, you peel and cook it how you want it,” he says. “We did the same with cacao, sourcing it carefully, processing it ourselves and making our own chocolate.”

He kept two sittings, offering an eight-course menu from 6pm to 7pm, thereafter a three- or four-, and, later, a five-course menu.

What’s key is to have a good team who love their work

In 2019, he got his Michelin star. A year later, just before the Covid-19 lockdowns began, he earned a second, an accolade he says was completely unexpected.

“I was shocked, and nervous due to the extra pressure. It was never part of the plan. We had no service team, no restaurant manager, no somm or bartender – my business partner [Oliver Bischoff] and I did service,” he says.

“I’m surprised Michelin were so open to giving us the first and then the second star.”

He was already raising prices and shifting the format of the restaurant every six months or so, but with the second star came new considerations. Diners began to question why there were no chocolates at the end of the meal and where the staff were to pull out their chair for them.

With extra staff required to offer a higher level of service, he raised prices comparable to other two-Michelin-star restaurants.

“I realised that Michelin stars only work at a certain price,” he says. “A restaurant needs to be expensive so people see the value, which is a shame as we always wanted to be affordable.”

“A lot of restaurants here are conservative and a pastry chef doing something so unusual, in a restaurant with no sign outside and covered in graffiti, and earning two stars for it, made them question their own style,” he says.

In 2022, he changed from two sittings totalling 50 covers to the one sitting of 15 courses and 25 covers that he serves today.

Does this next evolution suggest he is gunning for a third star? The extra recognition is unimportant, he says.

“What’s key is to have a good team who love their work,” he says. “We don’t have a sponsor, so we have to earn what we pay our staff, and I’m proud that we’re sustainable in this way. All our staff check in and out so there’s no overtime.

“It’s rare for a three-star restaurant, especially in Germany, to earn enough to pay their staff fairly.”