In Chinese culture, 60 years is known as jiazi, representing the full alignment cycle between heaven and earth.

The commemoration of Deng’s 120th birthday on August 22 comes at a most intriguing time. After four decades of spectacular growth thanks to Deng’s reforms, the world is again “standing at a crossroads of history”, as his modern-day successor Xi Jinping put it.

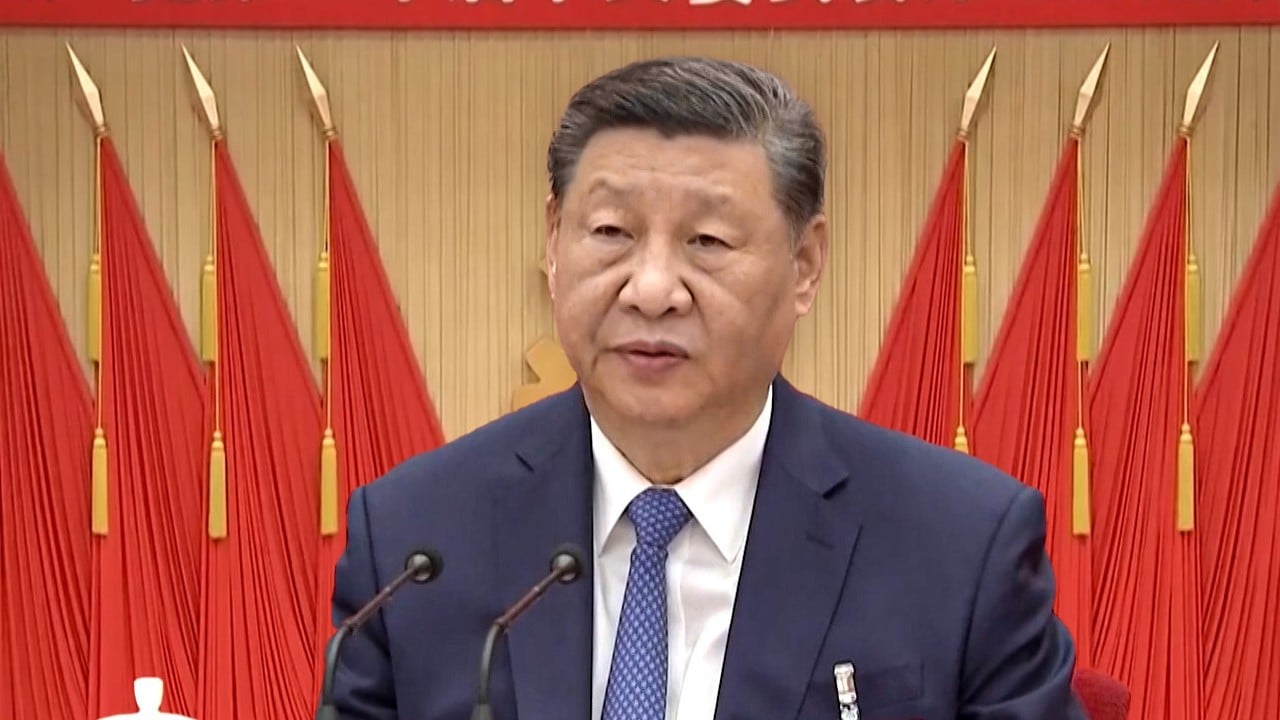

Comparisons between the two men are almost inevitable. Xi, said to be the most powerful Chinese leader since Deng, is often depicted in Western narratives as the “dismantler” of Deng’s reforms – an assertion that Beijing would angrily dismiss as a smear.

Xi, according to various official reports and his own speeches, regards himself as Deng’s true heir and the one to see through the great mission that Deng started – the rejuvenation of China as a great civilisation.

Although the two leaders differed in their strategies and approaches, closer examination reveals many core similarities.

Each of them faced critical moments that would decide the Communist Party’s very survival and reacted by breaking with the conventions and paths set by their predecessors.

Both Deng and Xi embarked on a zealous mission to restore China to its position as a great world power, and they shared a conviction that the Communist Party is indispensable to achieving that goal.

Deng was the first to warn that China must chart its own reform path and not blindly copy the Western model. He sneered at Mikhail Gorbachev’s “perestroika” reforms in the Soviet Union, even as they were widely praised in the West.

“My father thinks Gorbachev is an idiot,” Deng’s younger son, Deng Zhifang, once told a friend.

By dismantling the Communist Party’s power structure, “he [Gorbachev] will lose the power to fix the problems before people kick him out”, the younger Deng recalled his father predicting, ahead of the Soviet Union’s eventual collapse in 1991.

Deng Yuwen, former deputy chief editor of the Central Party School’s Study Times, also called Deng “a diehard communist”.

“He did not want anyone using his reform initiative to damage the party’s rule. He laid down the ‘Four Cardinal Principles’ to safeguard that.”

The cardinal principles required Chinese leaders to adhere to the socialist path, the people’s democratic dictatorship, the party’s leadership, and Mao Zedong’s Thought and Marxism-Leninism principles – the same message that Xi likes to stress.

“The most distinct feature of Comrade Deng’s thoughts and practices is [they start] from reality, from the general trend of the world and from the situation and conditions of China,” said Xi, in a 2014 speech to mark the 110th anniversary of his predecessor’s birth.

“A developing country like China would not rise if its people had no national dignity or the country lost its independence,” Xi said. “We should not belittle ourselves, forget our heritage or betray the motherland.”

Xi upheld Deng’s Four Principles and answered with his own “Four Convictions” – officially translated as the Four Confidences.

These demand that the party’s 99 million members demonstrate full faith in China’s path, its unique political theories and system, and its rich history and culture. The language and terminology used may differ, but the two men spoke with one voice.

Consensus, centralisation

However, each of them inherited a China facing drastically different challenges and conditions, and each responded with a unique approach.

Deng realised that his first task was to pull the party out of a quagmire of ideological infighting and shift the focus to economic growth. He opted for collective leadership – a consensus-building mechanism that gave the different factions seats at the table.

Meetings should be small and short … If you don’t have anything to say, save your breath … the only reason to have meetings is to solve problems

Many of the unwritten rules in Chinese politics were formed in the years that followed, including the customary retirement age of 68 for senior leaders and the immunity from prosecution for former top leaders.

These rules provided basic power-sharing and a mutual protection framework that made it possible for the factions to work together.

It was a design born out of pragmatism. Deng and his colleagues realised that factional and ideological differences would lead to little actual result and must be set aside.

If they could not reunite their divided party and refocus minds on economic development, the party’s very survival – along with the People’s Republic of China – would be in doubt.

While Deng was the unquestioned leader, he had the support of other party elders, such as Chen Yun – like Deng, a founding father of the People’s Republic – and other peers. In his book, Vogel called Deng China’s “general manager”.

Deng’s emphasis on pragmatism is best reflected in his speech at the closing of the fifth plenum of the 11th party congress.

“Meetings should be small and short. They should not be held at all unless the participants have prepared … If you don’t have anything to say, save your breath … the only reason to have meetings is to solve problems,” he said.

“There should be collective leadership in settling major issues. But when it comes to particular jobs or tasks, individual responsibility must be clearly defined, and each person should be held responsible.”

The principle of collective leadership was designed to revitalise the party, as well as to prevent any faction from total domination.

While it proved useful, its shortcomings gradually become apparent. The striving for superficial unity eventually led to extreme caution, inertia and a breakdown of party discipline.

Later party chiefs would increasingly struggle to assemble a support team of their own choosing or to carry out reform programmes that would upset entrenched interest groups.

This was most apparent under former president Hu Jintao, who expanded the powerful Politburo Standing Committee’s membership to nine to accommodate conflicting factional demands.

The decision-making body was half-jokingly referred to as the “nine dragons ruling the rainfall”, in reference to an idiom observing that when power is shared, no one is powerful enough to effect a downpour.

With no strong leadership at the top and responsibility spread across the team, party discipline broke down, breeding rampant corruption as well as abuses of power and even insubordination.

Xi responded to the crisis by launching the largest anti-corruption campaign in the party’s history and a drive to recentralise power. In the process, the unwritten rules – such as the exemption from prosecution of former top leaders – were shattered.

While the two leaders opted for opposing strategies, both Deng and Xi were aiming for the same goal – to refocus the party’s minds on the common goal of national rejuvenation.

And Xi, like Deng, is also known for his dislike of “empty talk”, often urging the party’s cadres to “roll up their sleeves and work harder”.

Xi’s move to recentralise power was based on his view that the party was in danger of losing its cohesion and being hijacked by powerful interest groups, in a repeat of Gorbachev’s Soviet Union.

Such concerns have deep roots in Chinese governing philosophy. Han Fei – whose teachings of 2,200 years ago formed the foundation of the Qin empire – said “the key to governing [a vast empire] with pressing issues on all fronts is a strong core”.

Xi cited this quote in a keynote speech to the Politburo Standing Committee on January 15, 2018 – two months before the National People’s Congress approved the amendment to the constitution removing presidential term limits.

Legacy and challenges

Deng’s reforms transformed China in just 30 years – half a jiazi, before heaven and earth could complete one full cycle of alignment – from one of the poorest countries to the world’s second-largest economy.

“If there is one leader to whom most Chinese people express gratitude for improvements in their daily lives, it is Deng Xiaoping,” Vogel wrote.

“Did any other leader in the 20th century do more to improve the lives of so many? Did any other 20th-century leader have such a large and lasting influence on world history?”

Yet the Chinese leader’s unparalleled success also created a host of problems. Towards the end of Vogel’s book – written in 2011, just a year before Xi’s ascension to power – the Harvard professor listed five challenges for Deng’s successors.

They were: to contain corruption; provide universal social security; preserve the environment; maintain the party’s legitimacy to rule; and to redefine and manage the boundaries of freedom. All have been top of the agenda under Xi.

“Things have changed so much … but China still follows the route set by Deng, aiming to achieve rejuvenation by the construction of a unique China, no matter how the party’s narrative put it,” said Victor Gao, a former foreign ministry official and a translator for Deng in the 1980s.

According to Gao, vice-president of the Beijing-based think tank Centre for China and Globalisation, Deng’s “vision and thinking remain relevant today” as the country “faces many challenges on how to open up to the world”.

“It calls for an outstanding leader who can see the big picture clearly and work from the right direction, just like Deng did,” he said.

Additional reporting by Sylvie Zhuang

)