A retired boomer receiving $1,662 in Social Security has moved in with roommates to help cover her medical expenses, stating that it’s the only way she can maintain a comfortable lifestyle.

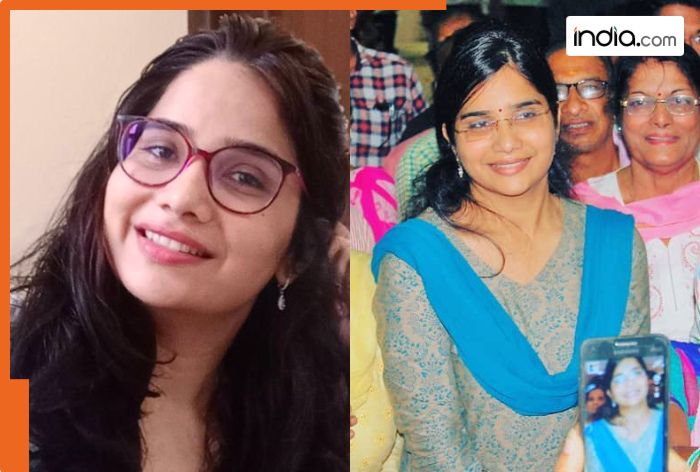

Marion, a 70-year-old single mother who raised two sons in Washington, often worked two jobs to provide for her family. Following a series of surgeries that left her unable to work, she decided to try a cost-saving strategy: living with roommates.

According to Business Insider, Marion decided to sell most of her possessions and leave her friends behind to move in with her sister and her sister’s partner in rural Ohio.

The high cost of living in Washington forced her to relocate, and she now pays approximately $500 in rent in Ohio, enabling her to save money and better afford her many medical bills. Even in a small town with only one stoplight, making ends meet on a $1,662 Social Security income is difficult.

“I now have roommates for the first time in my life, but it’s a way to live comfortably,” Marion told BI. “You got to do what you got to do.”

A Lifetime Of Moves And Rising Costs

Marion’s father was in the military, and her family moved around the country as a child. She was born in Germany and moved to Massachusetts, Florida, Michigan, and Texas. “We were never wealthy; we were your typical middle-class family,” Marion said.

Marion became pregnant at 17 and raised her child as a single mother. She later married a man who was not her child’s father and moved to Washington to be closer to his family. The couple had a child together, but they divorced four years later.

Marion raised her children north of Seattle while working as a cocktail waitress and taking on side jobs, which provided enough income to support her family. She spent 13 years at one chain restaurant and then transitioned to another chain for 18 years, working in managerial positions that offered higher pay.

“It was hard to raise your kids working that much and making sure that they were on the straight and narrow and not getting in trouble,” Marion said, noting she often made sacrifices so her children could live comfortably and get an education. “Sometimes I look back, and I don’t even know how I did it.”

Marion recalled owning a car that would fill up with smoke when it started, but she couldn’t afford to replace it. Desperate to provide a Christmas gift for her son, she once borrowed $50 from her boss, which took her three months to repay.

More than two decades ago, Marion retired early from her job due to extensive medical issues, including neck and back surgeries that left her unable to work the 50 to 60 hours a week her job required.

Marion relied on Social Security Disability Insurance payments to survive, but they were far less than her previous salary. Earning only about $1,200 a month, she struggled to make ends meet. Marion eventually filed for bankruptcy and lost her condo, after which she moved in with her mother for a decade until her mother’s death.

Marion was forced to cash out her 401(k) early due to the limitations of receiving SSDI benefits, and she spent a significant portion of her savings on dental work. In contrast, a 66-year-old retired teacher relies on a modest $1,601 monthly from Social Security to make ends meet. Despite having a 401(k), she hesitates to withdraw from it, fearing that she might deplete her savings too quickly.

Marion’s sons helped her pay some bills during difficult times, as her work hours were limited. She also earned additional income by selling painted bottles at a local art museum, bringing in approximately $100 monthly.

“I learned to adjust bit by bit. I learned where to cut corners, where to buy food cheap,” Marion said. “I would clean houses under the table. A few times a year, I would get an extra $200, $300, $500.”

During the first two years of the pandemic, government assistance and a temporary pause on rent increases allowed Marion to live frugally but comfortably. She initially paid $675 monthly in rent but saw it increase to $900.

However, last year, her rent jumped to $1,150 for a 600-square-foot one-bedroom apartment, a cost she knew she couldn’t afford on her $1,662 net Social Security income. When she applied for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, she was only eligible for $23 monthly.

“When you take $1,150 away from $1,662, that does not leave a lot for food, car insurance, gas, or internet,” Marion said.

The Search For Affordable Housing

There were few places in Washington where she could find significantly lower rent; even the administrative fees and security deposit would be challenging. She described her neighbourhood in Washington as having “deteriorated” over the past ten years and desired a safer, quieter environment. Knowing she didn’t want to be a burden on her two sons, she decided against moving in with them.

Marion considered moving in with her sister and her sister’s boyfriend, but it would require her to relocate across the country. She ultimately decided to sell her car, leave her home state of five decades behind, and move to Ohio. She went into debt for six months to afford a U-Haul and a new bed.

“I had to move, but I don’t have a network of people here,” Marion said. “I hardly know anybody, just my neighbours.”

Marion, her sister, and her sister’s boyfriend share a five-bedroom house in the small town of Mechanicsburg, which has 1,700 residents and only one stoplight. The total rent is $1,300; with utilities and other expenses, Marion pays between $500 and $600 monthly.

“I never thought that I would end up with roommates since that’s something you do when you’re young, not when you’re an old person set in their ways,” Marion said. “But it’s an option for older people to live with roommates because at my age and with my Social Security, living alone isn’t always possible.”

Marion’s sister and her sister’s boyfriend are financially better off than she is. They receive small pensions in addition to their Social Security benefits. Her sister’s boyfriend also works part-time to supplement their income.

Despite reducing her rent and saving money, Marion’s finances remain tight. During her last doctor’s appointment, she avoided cancer screenings and stress tests due to the $300 co-pay. She still owes $350 for glaucoma surgery, and she has paid between $35 and $40 for each specialist visit related to her arthritis and foot issues.

Her doctor recommended a foot cast to avoid surgery, but the cost of $500 is a barrier.”When you’re old and you get aches and pains, the hardest part is sometimes you don’t know if you’ve got a legitimate ache and pain or if it’s just old age,” Marion said.

“With my medical expenses coming up, I just don’t even know how to prepare for that except for waiting for October, when I’ll try to get a different medical plan,” she added. Marion’s greatest concern is saving enough money to live comfortably in her later years without burdening her sons.

People like Marion are finding creative ways to combat skyrocketing rents. For example, a woman traded her New York City lifestyle for a full-time adventure in the wilderness with her son to cut down her $2500 monthly rent to just $340 by moving into a tent in the woods. Now, she saves.

Given seniors’ increasing challenges in affording housing, home sharing has emerged as a viable alternative. Just as Marion’s decision to move in with roommates allowed her to reduce her housing costs, home-sharing offers a similar opportunity for seniors to share living expenses and enjoy the benefits of companionship.

Platforms like SeniorHomeshares.com, a free national non-profit service, offer seniors a safe and secure way to navigate home sharing. Seniors can create profiles detailing their living space, desired budget, location preferences, and ideal roommate characteristics. The platform’s algorithm then matches compatible profiles, allowing secure communication within the app.