The current Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Nicholas Reece, has said that if re-elected he would sell the City of Melbourne’s majority stake in the Regent Theatre and redirect the funds to support, among other things, a new arts festival.

The future of this venue matters. More than just an impressive piece of Melbourne’s heritage architecture – it also supports aspects of the city’s intangible cultural heritage.

A theatre for Melbourne

The Regent was built in the late 1920s as an opulent movie cinema. But as movie going habits changed, along with the rise of television and the dawning of the era of the multiplex, it could not compete.

State Library Victoria

In 1969, its owners Hoyts Cinemas sold the theatre to the City of Melbourne who closed it the following year.

Plans the council then had to demolish and redevelop the prime inner-city site would have likely succeeded had it not been for the intervention of the infamous Builders Laborers Federation. The union was “convinced that the theatre should be saved and restored”, and banned any demolition work from taking place.

Community sentiment was on their side. Eventually, the State Government and Melbourne City Council came to an agreement with theatre company The Marriner Group whereby it was fully refurbished as a venue for live performance.

The Regent reopened to great success in 1996.

But the fact it was so long under threat of becoming yet another example of Melbourne’s lost heritage demonstrates just how fragile the line can be between a great building’s survival and destruction.

Preserving ‘intangible cultural heritage’

These fights are not just about preserving nice bricks and mortar. They are also about preserving a building’s broader cultural and social function – something explicitly recognised in the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

This 2003 convention acknowledges cultural heritage also encompasses impalpable things like oral traditions, the performing arts, social practices, shared knowledge and traditional craftsmanship.

Australia has not adopted the convention. One of the on-going impacts of that decision is the concept of intangible cultural heritage does not have the kind of prominence or rhetorical force here it arguably should.

In the case of the Regent, it is easy to see how its built form also supports or enhances the kinds of intangible cultural heritage – such as a community’s performing arts traditions – UNESCO found to be worthy of protection.

While the theatre is a commercial operation, under the current ownership structure its principal role as a performing arts venue is not under threat. Would that continue to be the case were it to be entirely in private hands?

A risk to our churches, too

A similar issue of use arises around the fate of our disused churches.

The combined impact of declining church attendance, broader demographic changes, the creation of the Uniting Church in 1977, rising maintenance costs, and the need to fund compensation schemes has resulted in many historic church properties being sold into private hands

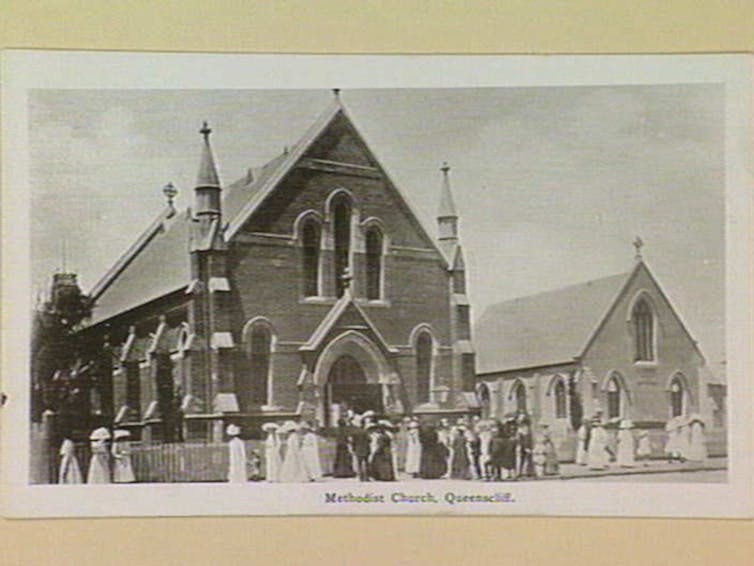

The former Methodist Church in Queenscliff is now a single four-bedroom house.

State Library Victoria

The spectacular 4,800 square metre site of the North Melbourne Uniting Church (including a magnificent pipe organ), was sold last year to an overseas investor, and quickly sold again, also to be turned into a private residence. The nearby Wesleyan Sunday School in Brunswick, is currently being turned into serviced offices.

There is a concurrent loss to the wider community, however, when these transformations away from public access and use occur.

Church buildings have traditionally provided us with a space that can serve as an oasis of calm, peace, and aesthetic beauty in our built environment – whether we are religiously minded or not. They are also often available outside service times for use as a meeting place, a rehearsal or performance venue, a lecture space, or a social event space.

All such uses benefit our broader community and wellbeing, and can also form part of our intangible cultural heritage.

Beyond that, the very existence of a church building is also usually the result of many generations of community investment. Some formal recognition of this investment should be in play when these buildings are sold into private hands.

A much better outcome for a disused church is that which befell St Peters Anglican Church, in the central Victorian town of Carapooee.

When it was put up for sale in 2021, the local community rallied around and raised the funds to buy the property, ensuring the building would still be available for community use.

Preserving both physical and intangible heritage

The fate of the Regent Theatre after it was closed in 1970 is another good example of how imaginative thinking and cooperation between various community stakeholders can help to preserve both a building’s physical fabric, and underlying social function.

Reece told The Sunday Age he was “confident” the space would remain a theatre after sale, but, as the paper also reports, there is no guarantee.

Once buildings fall out of public ownership, they frequently fall out of public use – and risk being lost to the community forever.

This is not just a risk for our theatres and churches. We could add to this list other community-servicing public infrastructure such as schools, town halls and post offices. None should be sold to the highest bidder without a full consideration of the accompanying loss to the community-at-large or their role in supporting our intangiable cultural heritage.

We can then better account for the real cost of sale to the communities these spaces once served.

In the absence of other formal protections, it is perhaps time for governments at all levels to consider introducing formal covenants or other protective measures over community-facing properties like the Regent Theatre. We can thereby help ensure that, alongside their physical form, something of their social function can also be preserved.