As I turn a corner, I see something else: amid a row of neatly parked vehicles is one that stands out as much for its individuality as its quaint charm. The aluminium body of the Series 1 Land Rover glows under the rising sun. A little ahead, there’s another.

I stare at the vintage beauties as townspeople amble past in the mountain freeze. I decide to spend some time in Manebhanjyang to find out more about the vehicles.

Designed by the Rover Car Company’s chief engineer, Maurice Wilks, Land Rovers were built in Solihull, near Birmingham, England, and launched at the Amsterdam Motor Show in 1948, a year after India’s independence from British rule.

Not just India’s Silicon Valley – why Bengaluru is now a cultural capital

Not just India’s Silicon Valley – why Bengaluru is now a cultural capital

Many were imported by British tea planters who stayed in India to continue running their businesses.

“Back then, the hills had bad roads and those that ran through tea gardens, whether in Darjeeling or those across Assam, were far worse, but the Land Rover could navigate this terrain with ease,” says Shahwar Hussain, a heritage car collector in Guwahati, India, who owns a Series 3 model (which were built between 1971 and 1985), when we speak in Darjeeling later.

“The missionaries also used it to travel to the interior areas in the northeast of India,” he adds. “Today, they belong to individual owners across the country. And no single place has as many as there are in Manebhanjyang.”

The British built a track from Manebhanjyang to mountain villages such as Chitrey, Meghma, Tonglu and Tumling.

“The people of Manebhanjyang used to regularly trade with those living higher up,” says Chandan Pradhan, a resident of Manebhanjyang and president of the Singalila Land Rover Owner’s Welfare Association. “They would transport essentials like salt, rice, lentils and flour, and bring back potatoes. All of it would go on mules until the first Land Rover arrived here.”

Manebhanjyang residents were quick to realise the utility of the four-wheel-drive vehicles over terrain that features steep inclines and precipitous drops. When the British started returning home in the 1970s, a few enterprising folk visited auctions to get their hands on these hardy vehicles, to use as taxis and transporters.

“A Land Rover could be bought for 20,000 to 25,000 rupees and it soon became a lucrative business for those who invested in one,” Pradhan says. “There was a time when there were around 300 of them running around these hills.”

Pasang Tamang, whose first driving lesson was in a Land Rover, recalls setting off in the dead of night with heavy loads and travelling for close to seven hours while delivering supplies to villages. After a short break, he’d turn back to get home by sundown.

“I would carry everything from live animals to rations and medicines. There would be villagers eagerly waiting for my arrival. There was no road as such, just dirt, stones and boulders, and rivulets running down the slopes. And of course, the unpredictable mountain weather,” he says.

“But the Land Rover made it through everything – slush during heavy downpour, heavy snowfall and frozen black ice that lay in the shadow areas.”

Nowadays, besides supplies, this mountain track is taken by hundreds of tourists to Sandakphu, a mountain in Nepal that presents glorious views of Himalayan giants such as Kanchenjunga, in the foreground, and Everest, Lhotse and Makalu in the distance.

Although a section of the 31km (19-mile) road to Sandakphu is now paved, a four-wheel drive is still needed to get to the top.

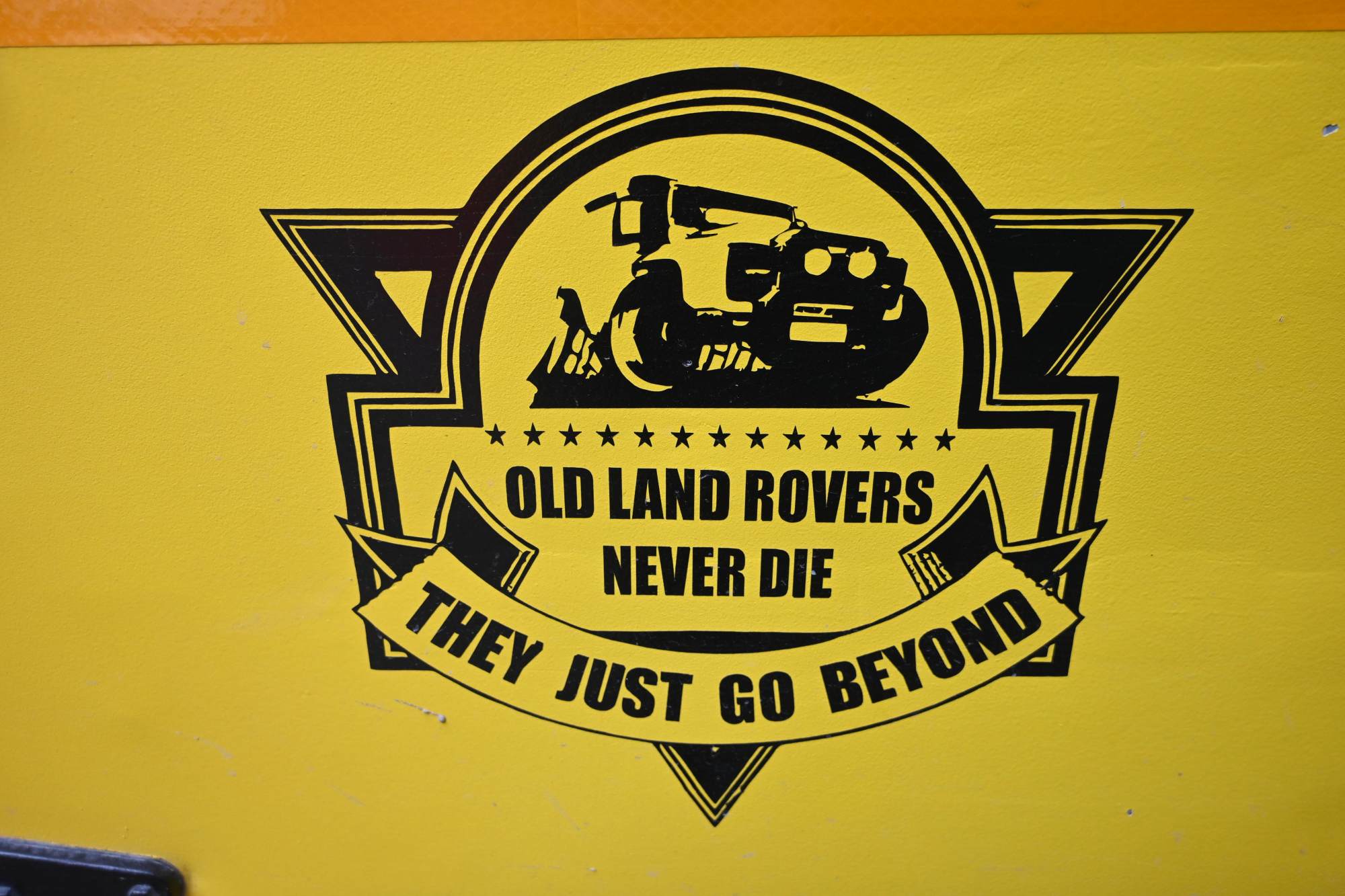

“Tourists prefer newer vehicles since they are a lot more comfortable,” says Anil Tamang, a resident who used to drive tourists around in his Land Rover. “Only a few nostalgic folks choose to ride a Land Rover for the experience. It has led to a drop in their demand and only 35-odd Land Rovers survive in Manebhanjyang.”

Owners have other factors to contend with. With every passing year, spare parts get harder to find. So while the aluminium chassis have weathered the elements, most owners have had to make practical choices, such as replacing the original petrol engines with readily available diesel substitutes.

Tenzing Tashi Bhutia is an owner who has preserved an original Land Rover engine – although it is tucked away under a cover outside his home. He also has a basement full of spares that he has gathered over the years.

“There was a time I would go in search of Land Rovers in disuse, buy them cheap, and dismantle them with my own hands to stock the spare parts. Even today, I rush over when I hear of someone discarding their vehicle,” Bhutia says.

“There are heritage car owners who want a Land Rover with all its original parts intact – everything from the engine to the headlamps. So I’m just waiting it out until the day I’m ready to part with my beauty.”

Jagat Rana is the mechanic in Manebhanjyang who most Land Rover owners approach to deal with daily wear and tear.

“All the learning for me happened while driving a Land Rover,” says Rana, who once drove one for someone else. “It needs a lot of patience to maintain these vehicles and I get at least one complaint each day. While they are sturdy, they’re also quite old so they develop oil leaks that can be a task to fix, especially if you are on the road.”

The Singalila Land Rover Owner’s Welfare Association was established in 2004 to unite the dwindling number of owners in Manebhanjyang. The vehicles’ fate has hung in the balance since 2018, when a local court ordered the phasing out of Land Rovers as commercial vehicles, due to their age.

“Declaring Land Rovers as heritage vehicles is of no use to us owners,” Pradhan says. “We’ve written to the government to make an exception and issue permits to run them locally for tourism.” That request is still being considered.

“Since these are old vehicles, there’s no insurance coverage either,” Pradhan adds. “We regularly get enquiries from buyers, who are ready to shell out as much as 12 lakh [US$14,400] to own one [for a private collection]. And without a plan for the future, most [current owners] may part with their vehicles.

“I feel like the Land Rover will soon disappear from Manebhanjyang.”

My two days in the town have flown by and Shingo dai comes around looking for me, his vehicle packed and ready to get moving again. There’s a smile on his face as he sees me gazing at a Land Rover, sitting pretty in yellow.

“Ever since I was a child, I’ve associated Manebhanjyang with Land Rovers. We would sit up and count how many we could spot while driving past this town,” he says. “This is their home.”