The Great War was the conflict that first saw large-scale submarine warfare.

Subs had appeared as early as the American Civil War, in the 1860s, where both the Union and the Confederacy built submarines. But it was the Russo-Japanese war (1904-1905) that really made navies around the world sit up and take notice.

No submarine on either side saw action, but both sides began to commit serious money and built up fleets of modified American-built subs. It was clear that underwater warfare would now be a part of any future conflict between major powers.

A decade after the Russo-Japanese conflict, Europe collapsed into World War I and the Royal Navy Submarine Service boosted its meagre fleet of half a dozen subs to 42, all made by Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness in northwest England.

By the Armistice of 1918, the Submarine Service had expanded to 133 vessels while the number of submariners had grown from 1,418 to 6,655. The damage subs could do was obvious.

Germany and Austria-Hungary’s combined 140 U-boats sank almost 5,000 merchant ships during the war (roughly a third of the world’s merchant-ship fleet), killing around 15,000 allied sailors.

The submerged threat needed countering, and anti-submarine mines were soon invented, depth charges added to the weaponry of enemy shipping, and spotter planes flew across the sea looking for dark patches in the semi-transparent waters, shapes at which to direct surface ships loaded with depth charges.

It was a messy business. Anti-submarine mines sank as many innocent fishing trawlers and steamers as they did battleships.

Submarine warfare was partly responsible for bringing China into World War I on the side of the allies. On February 1, 1917, Germany began “unrestricted submarine warfare”, whereby its feared U-boats were ordered to sink any and all merchant shipping, such as freighters and tankers, without warning.

Soon after the order was given, a U-boat sunk the passenger ship Athos, causing the loss of 543 French-recruited Chinese labourers heading from Shandong to the European battlefront.

China subsequently severed diplomatic ties with Germany in March and declared war on the Central Powers on August 14, 1917.

Hong Kong was not unfamiliar with submarines either. The Royal Navy China Squadron, with bases at Singapore, Weihai and Hong Kong, had included three C-class subs on the eve of war.

They were all built around 1909, 135 feet long, petrol-driven vessels that could run at 14 knots surfaced. They were stuffed with torpedoes and crewed by 16 officers and men.

The first Asian submarine flotilla had departed Portsmouth in Britain, bound for Hong Kong, escorted by the submarine depot ship HMS Bonaventure in February 1911. Large crowds reportedly waved them off at Spithead.

They were able to go part of the way to Hong Kong – 9,618 nautical miles – under their own power, but at times, such as the last leg of the voyage, from Singapore to Victoria Harbour, were towed.

Although they apparently never saw combat, the C-class subs clearly had a deterrent effect. Vice-Admiral Robert Hamilton Anstruther, the most senior Royal Navy officer on the China coast during World War I, told the Nottinghamshire Evening Post that he believed the subs at Hong Kong “prevented German raiders from coming too near the port”.

The Germans had no subs in Chinese waters during the war.

In the summer of 1917, with submarine warfare at its height in the North Sea, Charles Little, Commander of the Grand Fleet Submarine Flotilla (who would later become Commander-in-Chief, China Station), ordered the three subs to be towed home from Hong Kong to join the North Sea naval battles.

Then in 1919, with the war in Europe over and Germany defeated, Commander Little found himself able to redeploy his significantly grown flotilla of submarines across the Empire.

He subsequently ordered a number of the latest L-class subs to Asia for duty in the waters around Hong Kong, though ranging as far as Shanghai, Japan and Singapore.

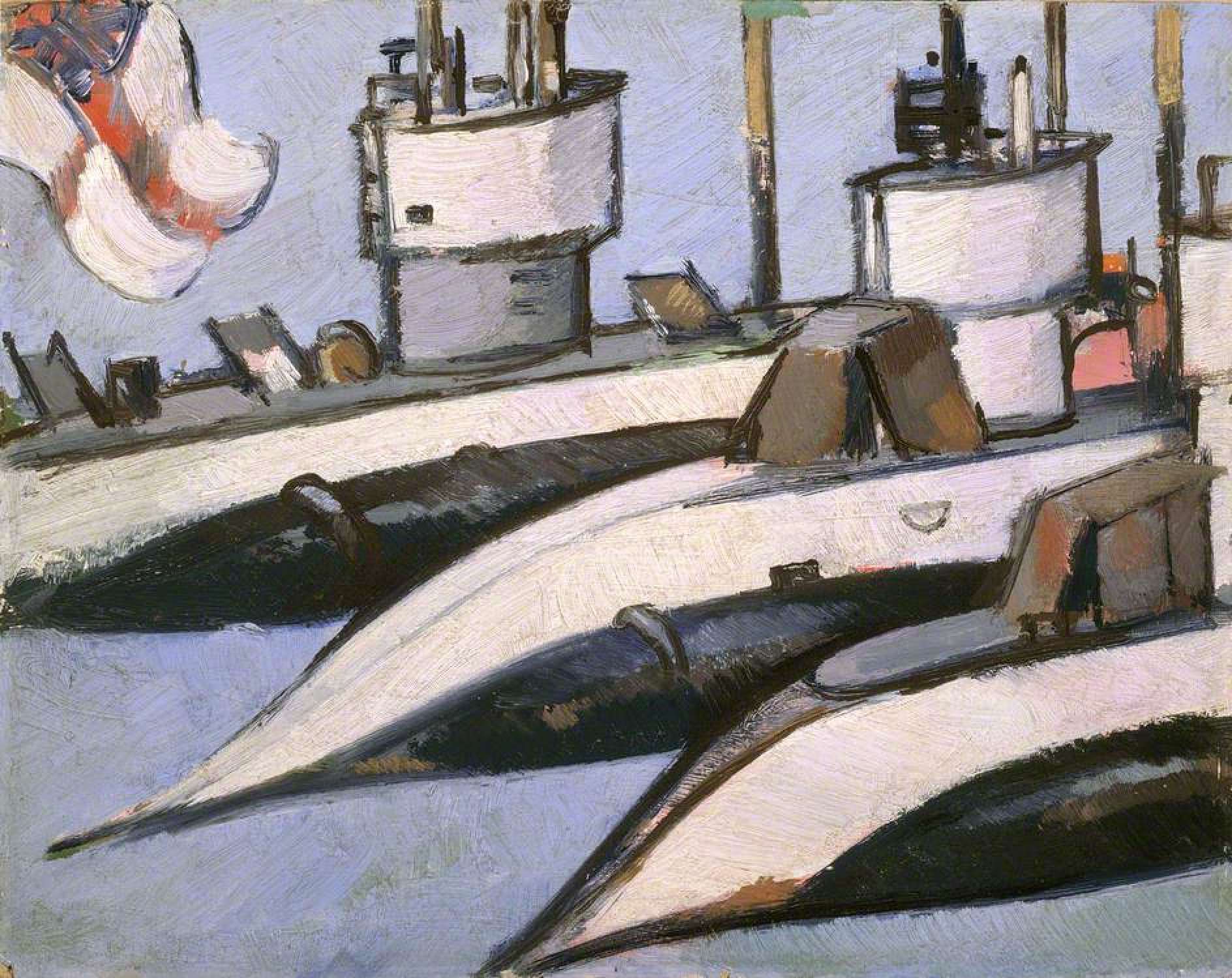

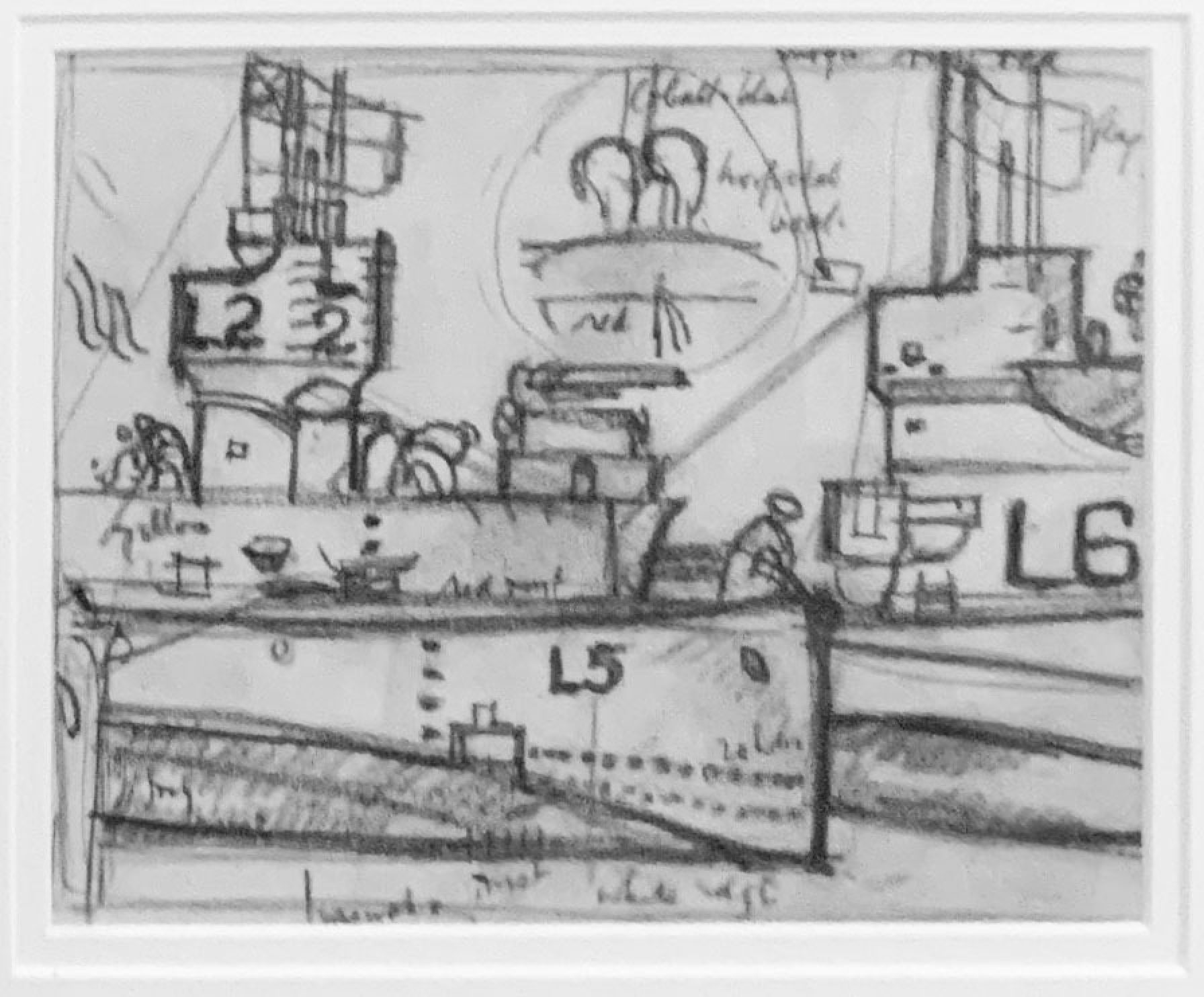

They were accompanied on their voyage out by the submarine depot ship HMS Ambrose (strikingly still painted in its wartime dazzle camouflage). The Scottish watercolourist John Duncan Fergusson captured the brand-new L-class subs at Portsmouth Naval Docks in 1918, just before their departure east.

The L-class subs of the so-called Fourth Submarine Flotilla were securely stationed in Hong Kong waters by January 1920.

These subs were new beasts in southern Chinese waters – serious upgrades on the old C-class submarines.

They had been completed just before the Armistice so had never seen active service. They were certainly bigger than anything seen in Hong Kong before – the largest were 235 feet, a full 100 feet longer than the C-class subs.

Each had a crew of 35, could travel at 17 knots on the surface and just over 10 knots when submerged.

They had a range of a then phenomenal 3,200 miles with six 18-inch torpedo tubes – four in the bow and two broadside – carrying 10 reload torpedoes and with a four-inch deck gun to fire when surfaced.

Arguably the L-class subs were the best in the world in 1920, although the American submarines of the US Asiatic Fleet that called at Hong Kong in 1922 might have challenged that claim.

Their mission brief was simple – to hunt and eradicate the pirates infesting the waters around Hong Kong.

By the 1920s the South China pirates were aware that their traditional junks could not outrun the more powerful vessels of the Royal Navy. They were sitting ducks to be blown out of the water.

Consequently pirates took to hijacking vessels – coastal passenger steamers and cargo ships – looting the freight, relieving the passengers of their wallets, watches, jewellery, then offloading everything valuable, often including hostages (invariably Chinese passengers) and making their escape by junk to the mainland, most notably the pirate haven of Bias Bay (Daya Bay), in Guangdong province.

This strategy presented a new challenge to the Royal Navy. They couldn’t simply attack and blow up civilian ships – the risk of innocent casualties was too high. They had to try and intercept the pirates between the looted vessels and their lairs.

The pirates, however, had a highly organised, and well financed, intelligence system that operated in Hong Kong, Guangdong and as far up the China Coast as Shanghai. They always seemed to know when Royal Navy ships were in the area.

The answer? Patrol stealthily and hunt the pirates from under the waves rather than above.

It was a solid enough plan. The L-class subs could silently and invisibly patrol the major coastal sea lanes up the Guangdong coast to Shanghai and even into northern China. They could cover the particularly pirate-congested waters between Hong Kong and Macau and through the Taiwan Strait, too.

They could move rapidly, unseen, only occasionally surfacing. Pirate junks attempting to flee hijacked vessels for pirate lairs – not just Bias Bay and the numerous coves and inlets of the Guangdong coastline, but also the then fairly remote and loosely administered Coloane in Macau – could be intercepted, waylaid by machine-gun-toting surfaced subs and Royal Navy boarding crews.

In extreme circumstances the junks could simply be torpedoed and sunk.

Even so, the Fourth Submarine Flotilla was not invulnerable either.

Disaster struck on Saturday, August 18, 1923, when a massive typhoon hit Hong Kong. Winds of 195km/h (121 miles/hr) lashed the harbour, heavy rainfall washed out many areas, including much of Happy Valley and the adjacent village of Wong Nai Chung (long since demolished).

A cable between the submarine L9 (the Royal Navy had not yet started to give more individual names to its submarines) and a buoy gave way. L9 swung round and struck the Royal Navy Yard sea wall before the crew on board could drop anchor.

The order was given to abandon ship and the crew – luckily only four of the 35 total members were aboard – got ashore.

One crew member leapt over the side and swam to a nearby yacht buoy and clung to it before men ashore could get a rope and pull him to safety.

But then L9 swung again, buffeted by the strong winds, colliding with a moored merchant ship. A bulkhead gave way. L9 sank to the bottom of Victoria Harbour.

Remarkably, after the typhoon abated, L9 was salvaged, repaired and went back into commission, hunting pirates for another four years before being scrapped.

Submarines did not stop the scourge of piracy in southern China, however. In the mid-1920s, pirate hijacking continued unabated.

There was a rare level of agreement and cooperation between the colonial administration in Hong Kong and the Guangzhou authorities on the need to stop piracy between the British colony and Guangdong waters.

The Guangzhou chief of police even visited Hong Kong in 1924 for talks with the Royal Navy on joint anti-piracy activities.

Portuguese authorities, feeling a little chagrin thanks to the island of Coloane having become a notorious pirate haven, stationed two additional battle cruisers, joining the two already deployed.

Slightly later they established a Naval Aviation Centre in Taipa, with spotter planes that could join the hunt for pirate vessels.

Yet the pirates persisted. For every one operation shut down another two popped up elsewhere. The political situation in republican China was unstable, the economy fragile, the tradition of piracy too deeply rooted in many coastal communities, and the treasure to be had from raiding passenger steamers and cargo vessels just too tempting.

Still, the Fourth Submarine Flotilla proved its worth. If the pirates knew subs were in their area they simply stayed home, so stealth was the name of the game.

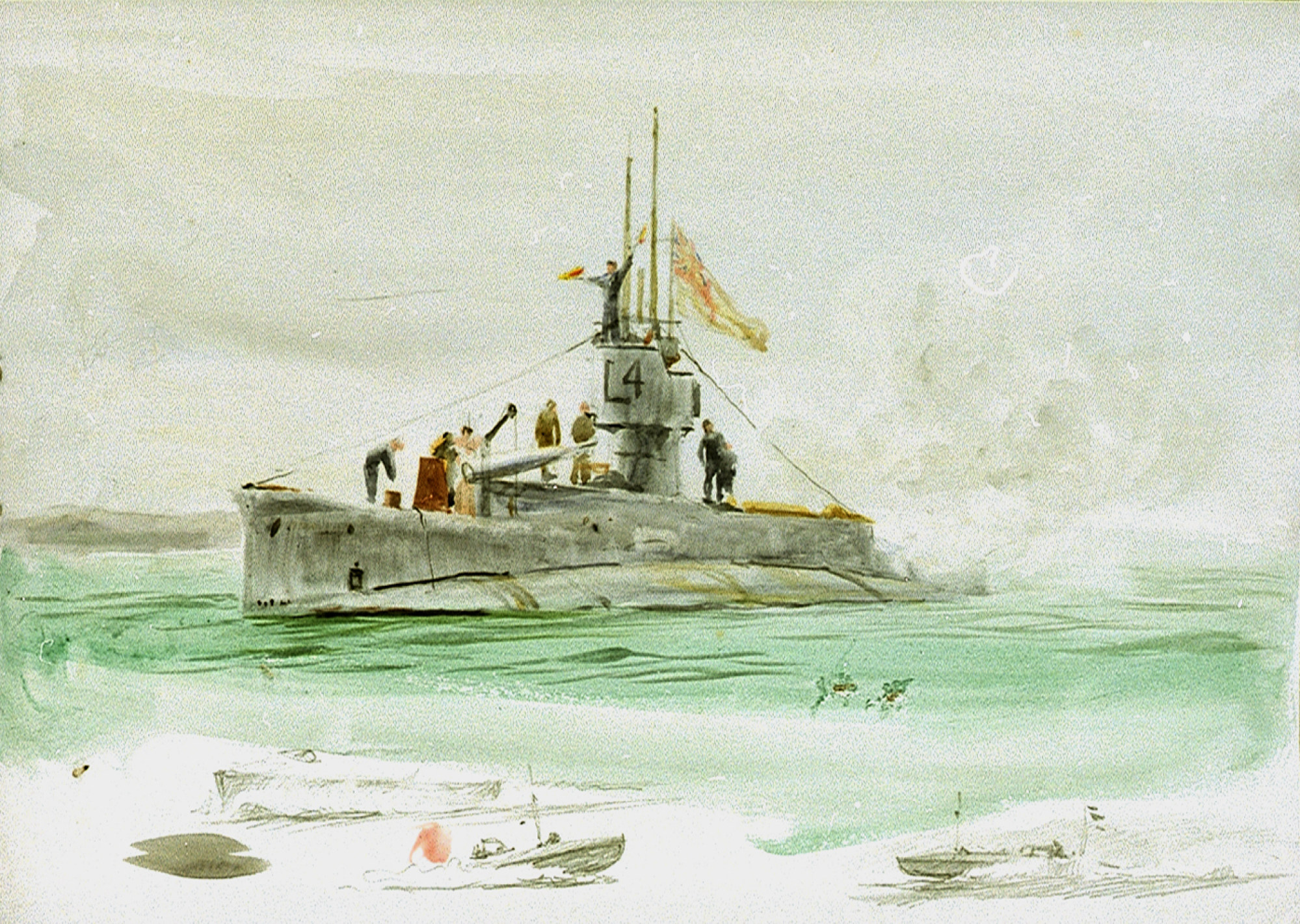

In early October 1927, two subs, L4 and L5, slipped out of Victoria Harbour. It was said they were going on routine patrol but they were headed directly to the most notorious pirate lair of Bias Bay, to the east of what is now Shenzhen.

At the entrance to the bay the subs split up, L5 to venture into the bay and L4 to guard the entrance. As a well-sheltered inlet, Bias Bay was a mass of fishing junks, sampans and other small craft. It was impossible to tell genuine vessel from pirate or smuggler.

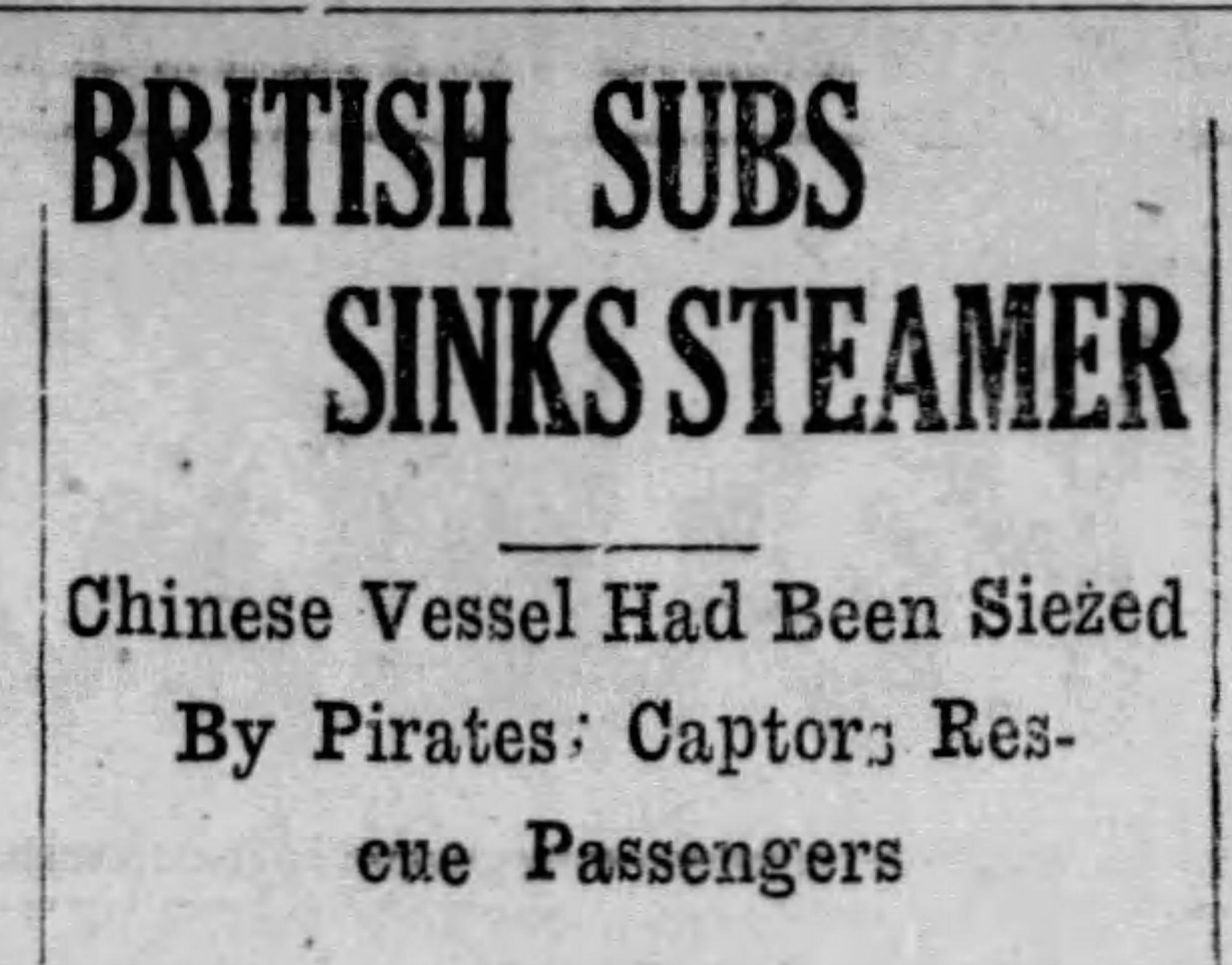

Word came to Lieutenant Frederick Halahan, commanding L4, that a passenger vessel of the Chinese-owned China Merchants Steam Navigation Company (CMSNC), the SS Irene, had been hijacked by 18 armed pirates.

Halahan decided not to use his torpedoes as the result would simply be a destroyed and sunk ship probably with the loss of all hands, civilian and pirate. Instead he gave the order to surface and prepared his four-inch deck gun.

Halahan switched on his surface spotlights, lit up the Irene, ordered her to halt, and fired a warning blank. It was ignored, so he fired a live round that killed a pirate hijacker on the Irene’s deck.

The pirates ignored Halahan while attempting to make for shore, secure in the knowledge that they could disappear into the hinterlands with their plunder.

L4 opened fire. Flames could be seen coming from the stricken vessel. Halahan signalled to L5 that he could see lifeboats being lowered from the Irene. L4 and L5 lowered boats each with one officer and one submariner aboard and cautiously approached.

The pirates had lain in wait. When the two small boats came closer they appeared on deck and opened fire. They were not about to surrender, knowing full well the penalty for piracy was execution.

Seeing their crews shot at, L4 and L5 opened fire with their deck guns. A round hit something flammable in the engine room. A giant explosion lit up the night sky over Bias Bay.

The Irene was abandoned as passengers and pirates alike scrambled to the lifeboats while some jumped overboard.

A total of more than 200 passengers and crew were rescued and transferred to the destroyer HMS Stormcloud, and a minesweeper, HMS Magnolia, that had both rapidly made their way to Bias Bay after Halahan reported sighting the hijacked Irene.

The fire aboard the Irene was put out; 14 passengers were lost, presumed drowned; the Irene sank the following day.

The pirates attempted to hide among the rescued passengers, although in the end, 17 were found guilty and hanged in Hong Kong.

The directors of CMSNC attempted to sue Halahan, but failed as naval commanders had the authority to sink any vessel controlled by pirates. Eventually CMSNC salvaged the Irene and she went back into service.

So ultimately, was the deployment of subs to Hong Kong in anti-piracy duty a success or a failure? Certainly the scourge of pirate hijackings didn’t stop.

The case of Bias Bay and the Irene perhaps showed that the L-class subs were a bit of a blunt instrument – they could shoot torpedoes or rain fire on vessels, but the likelihood of destroying ships and killing innocent civilians was high.

Even though the Bias Bay operation had shown that subs could pass unnoticed beneath the waters, the pirate intelligence networks were such that they invariably knew when subs left port on patrol and simply avoided them.

Faced with a wave of hijackings, the Hong Kong government instead enacted legislation requiring shipowners to station armed guards on board ships, use caging to separate passengers and crew, better protect engine rooms and quarterdecks from infiltration, and better search passengers boarding steamers.

The measures had some effect but could not totally eradicate the seaborne scourge.

It seems the Admiralty in London agreed. In March 1928 HMS Ambrose and six of the L-class subs were recalled to Britain, with a couple redeployed to north China and the newly built-up naval base in Singapore.

L9, the sub that had been so battered in the 1923 typhoon, was auctioned off in Hong Kong for scrap.