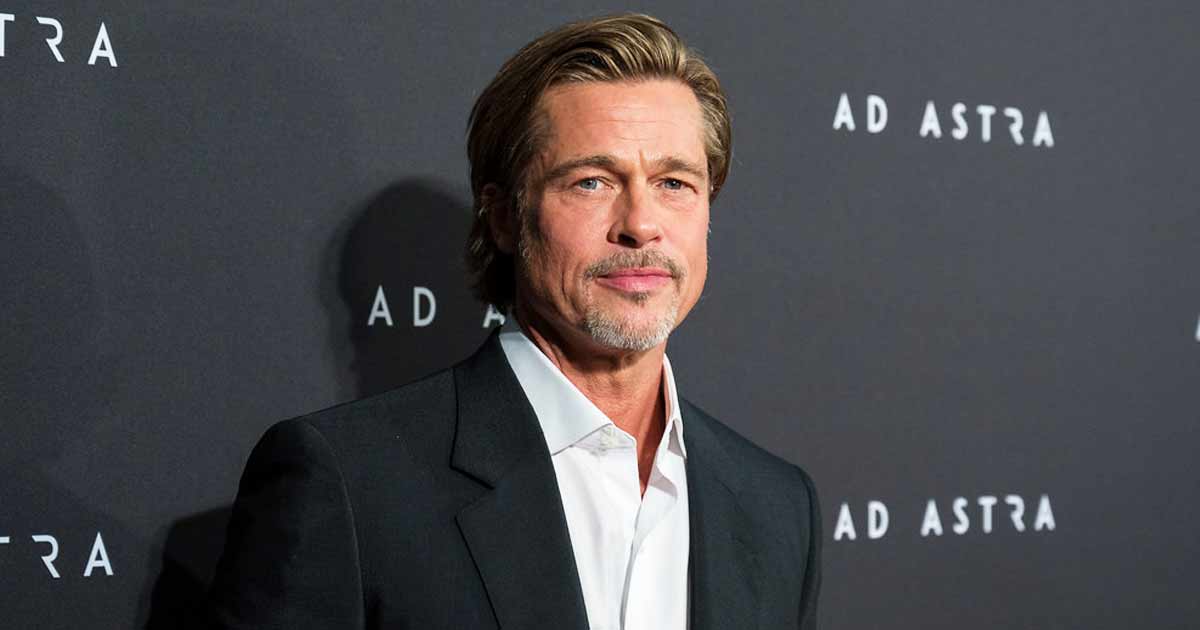

David Fincher is done fighting over Fight Club. The iconic director has faced criticism from every corner, with myriad labels labeling Tyler Durden—a character brought to life by Brad Pitt—as a symbol of toxic masculinity, racism, and misogyny. But now, Fincher steps into the ring to defend his creation. He sees Tyler not as a role model but as a cautionary tale, misunderstood by many who missed the film’s point.

You’d think a movie from ’99 would have faded into cinematic obscurity, but here we are, still discussing its legacy. Fincher expressed his frustration clearly: “It’s impossible for me to imagine that people don’t understand that Tyler Durden is a negative influence.” He challenged the audience to recognize the film’s toxic masculinity critique rather than embrace it. Fincher was not just defending his work; he was confronting a culture that had taken his art and twisted it into a disturbing rallying cry for groups like the Proud Boys.

In a world where art is subjective, Fincher shrugged off the misinterpretations of his film. He likened it to how viewers might perceive a Norman Rockwell painting or Picasso’s Guernica, stating, “We didn’t make it for them, but people will see what they’re going to see.” This highlights a fundamental question: Can an artist control how their work is perceived, or does it become a Rorschach test reflecting society’s darkest corners?

I’ll admit it: Like many other boys coming of age after 1999, I adored Fight Club. I was too young to catch it in theaters, but it was a staple among my peers by the time high school rolled around. I longed to join the ranks of those cool kids who could wax poetic about consumerism and rebel against the establishment. Who didn’t want to channel their inner Tyler Durden while smoking in the church parking lot or shopping at Hot Topic while contradicting the anti-consumerism they professed to embrace?

Pitt’s Tyler Durden represented an unattainable ideal for young men like me. I wanted to embody his anarchic spirit, break free from societal shackles, and feel something real. It’s a rite of passage for angst-ridden teenagers yearning for freedom. I mean, kids at my school even started their Fight Clubs in the safety of parents’ basements, all inspired by the film’s reckless allure.

But as I matured, so did my perspective on Fight Club. Twenty years later, I realized it didn’t age well. The film popularized a toxic brand of masculinity that found its way into the hands of online trolls and alt-right ideologies. It was guilty of misogyny and fell short of addressing mass consumerism, its supposed central theme.

I recently revisited the film as we marked its 20th anniversary and questioned its effectiveness. The references that once captivated me had become parodies of themselves. The posters of Pitt’s chiseled abs and the infamous soap had lost their luster. Critics and commentators have noted that Fight Club has not held up well in a society grappling with the consequences of male aggression and entitlement.

So, what is Fight Club’s lasting legacy? Can a film that resonated with a generation of young men still hold any relevance? As we grapple with how society views masculinity and consumerism, Fincher’s work invites us to reflect on the movie itself and how we interpret and embrace the art that shapes our identities. While Fight Club may have had its moment in the sun, its shadow continues to linger in masculinity and cultural critique discussions.

For more such updates, check out Hollywood News.

Must Read: When Salma Hayek Refused To Go Out With Donald Trump & He Tried To Humiliate Her For Being Short: “He Called & Left Me A Message…”

Follow Us: Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | Youtube | Google News