Two weeks ago, just before the start of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, Nike began airing its major Olympic ad campaign. Typically, these spots are beautifully produced paeans to ambition, effort, and excellence—Olympic ideals on sale for a popular audience. They have titles like “Unlimited You” and “Find Your Greatness.” But this one is different. Set to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and narrated gruffly by Willem Dafoe, in full comic-villain mode, it opens with a shot of a sweaty little girl with fierce blue eyes, before cutting to LeBron James, who is wearing the same angry gaze. “Am I a bad person?” Dafoe says, his voice a low taunt. He recites a litany of qualities he possesses: obsessiveness, deceptiveness, selfishness. “I have no empathy! I don’t respect you!” he cries, as the French basketball phenom Victor Wembanyama cackles after a block. (The soliloquy seems to owe something to Daniel Plainview.) His voice picks up pace and intensity. “I’m delusional! I’m maniacal!” There are shots of Serena Williams, Giannis Antetokounmpo, Sha’Carri Richardson. There’s Kobe Bryant, and more Kobe Bryant, his face a snarl. “What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is mine,” Dafoe rants. The piece ends with a firework burst of triumphs—goals, roars, knockouts, taunting shrugs. “Does that make me a bad person?” Dafoe sneers as the words “WINNING ISN’T FOR EVERYONE” flash on the screen.

There’s a thin line, sometimes, between being a champion and being a psychopath. What is really striking about the commercial is not the perspective that it presents but that it celebrates that view in connection with the Olympics. The Olympics, after all, are supposed to represent a form of striving that is on the other side of that thin line. At the Games, suffering isn’t a sign of some pathology but a path to transcendence. Sports are a moral education, shaped simultaneously by limits and freedom, requiring mutual respect for fairness and effort, in which competition serves not as the point but as a personal test. “The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part,” the founder of the Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, famously said, “just as in life, what counts is not the victory but the struggle.” Those words are the basis of the Olympic creed.

That’s the idea, anyway. The Olympic philosophy—which the International Olympic Committee, with its usual self-importance, refers to as “Olympism”—became something of a joke a long time ago. There’s been too much graft involving the I.O.C., too much racism, too much hypocrisy, too much doping, too much money, too many dictators, too many double standards for women. But some of the old ideals persist, in spite of all that. And the conflict between these two philosophies of sport is one of the underlying tensions of the Games. Perhaps nowhere has that been more evident than in the drama surrounding U.S.A. basketball.

The 1992 U.S. men’s basketball team, nicknamed the Dream Team, is the standard against which all subsequent U.S. basketball teams are held, and which they all fail to meet. The team won every game, by an average of nearly forty-four points. It had Larry Bird, Charles Barkley, Magic Johnson. Most of all, it had Michael Jordan. Jordan brought to the Olympics his vast audience, his cool. He brought Nike. Jordan was already a global superstar; the Olympics made him an icon. It was win-win. Amateurism was dead, if it had ever really existed. Jordan was a winner, and a psychopath. He set the mold and sold it. Then came Kobe Bryant, with his monomaniacal competitiveness forged in Jordan’s image. Now every N.B.A. player talks about revering the Black Mamba, as Bryant was known, and his ruthlessness.

It’s often said that a coach’s most important job is managing his players’ egos. That’s hard enough on a regular N.B.A. team; what about U.S.A. Basketball, a team almost completely made up of All-Stars? There’s LeBron James, who is thirty-nine years old, and whose carrying of the flag for Team U.S.A. through the rain during the Opening Ceremony in Paris became a meme comparing him to George Washington. There’s also Anthony Edwards, who is twenty-two, and who declared himself the team’s “No. 1 option,” not to mention Joel Embiid, an N.B.A. M.V.P. who recently announced that he probably would have been the best player in history if not for bad luck with injuries. And there is Kevin Durant, who has a history of starting burner accounts to defend his honor against strangers on the Internet. And so on.

Steve Kerr, the head coach of the team, has a sizable ego, too—you don’t survive a punch from Michael Jordan without one. (Maybe you don’t receive that punch, either.) But he also knows how to manage big egos, which is a big reason why he was given the job. It looks like an easy one. The U.S. may have the deepest, most talented roster in history. Of the twelve players, there are eleven N.B.A. All-Stars, four Most Valuable Players, and six N.B.A. champions. They have seven returning Olympians, and that doesn’t even include Stephen Curry, who is one of the best players in history. They have a collective N.B.A. payroll of around half a billion dollars. When it comes to star power, no other team in this year’s Games is in the same galaxy. Japan has a single N.B.A. player and multiple guys who are my height, or shorter. South Sudan has talented and gritty players but doesn’t have a single indoor court in the entire country, according to the forward Wenyen Gabriel. France lost to Dennis Schröder’s Germany.

But Kerr’s job is harder than it looks. First, there are the expectations: win gold, and you’ve simply done your duty; lose, and go down in infamy. Then there’s the question of getting players who are all used to starting and starring for their teams to adapt to different roles. And the gap between the U.S. and the rest of the world has been closing for years. (The 1992 Dream Team did its job of exporting the N.B.A. perhaps a little too well.) Now the best player in the world isn’t from the States. Nor, you could argue, is the second, or the third, or the fourth. This past season, the best American-born player was probably Jayson Tatum, who just won a championship with the Boston Celtics. In U.S.A. Basketball’s opening game, against Serbia, Kerr declined to play him at all.

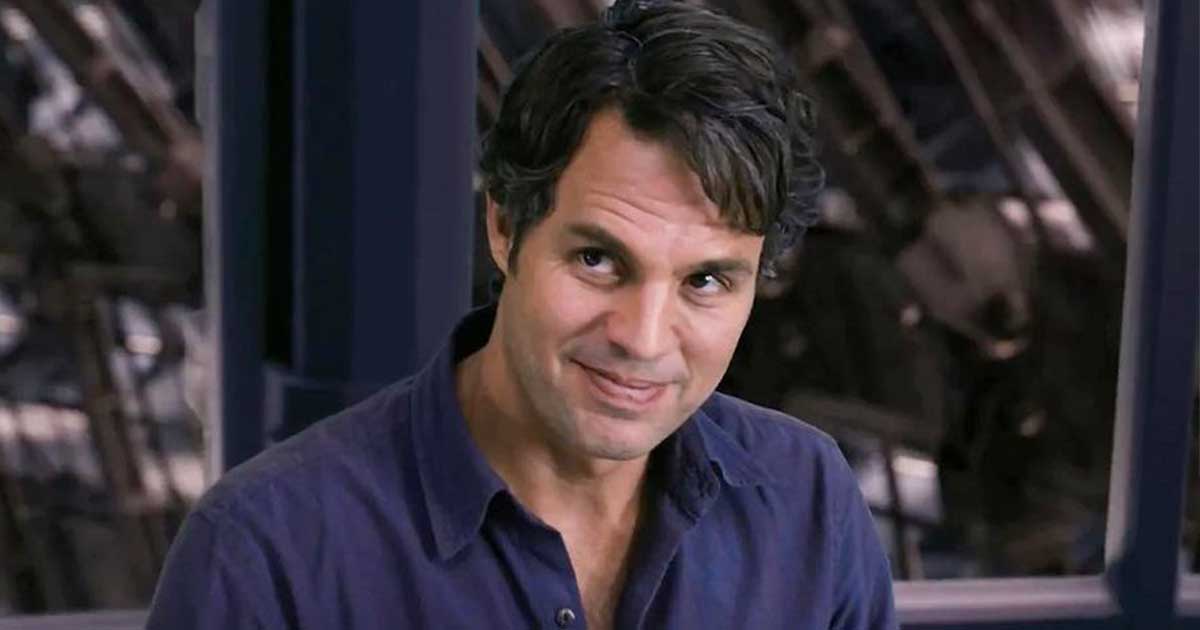

Tatum sees himself as one of Bryant’s heirs—he requested No. 10 for his national-team jersey, the number that Bryant wore in the Games—the connection has always seemed a little funny. Tatum, for all his obvious competitiveness, comes across as affable, nice. He seems to think, sweetly, that winning is the thing he needs to do in order to be seen by everyone as a winner.

When Kerr told him, ahead of the game against Serbia, that the minutes he’d been getting would probably go to Durant, who was coming back from a calf injury, Tatum responded as Kerr knew he would—like “the ultimate pro,” Kerr said afterward. It was a reasonable decision. Olympic contests are not exhibitions, and rotations in games with stakes rarely run twelve deep. Kerr’s teams, at their best, have an almost egoless flow: waves of backdoor cuts, relentless off-ball movement, constant passing. It’s a style not perfectly suited to Tatum, who is an unselfish player but who has a habit of holding onto the ball. Plus, Tatum, who played long minutes well into June, during the Celtics’ championship run, had a few rough games during the U.S. team’s spotty exhibition rounds. Serbia is led by the three-time M.V.P. center Nikola Jokić, and Kerr went with a bigger lineup. It paid off: Durant hit his first eight shots, and the U.S. won by twenty-six points.

Kerr’s decision not to play Tatum got so much attention you might have thought the team had lost. Kerr was put on the defensive; he said he “felt like an idiot” not playing Tatum, that he knew how great he was; he stressed the importance of matchups. He said that Tatum would be needed in the next game, against South Sudan, which boasts greater speed and athleticism around the perimeter than Serbia has.

All of this was, actually, a little idiotic, and more insulting to Tatum than less effusive praise would have been. Three days later, against South Sudan, as promised, Tatum was in the starting lineup. This time, Embiid, who’d looked awful against Serbia, didn’t play. This was reasonable, too, but it only added to the questions that people had for Kerr. Was the switch made out of pity, or public pressure? Was Embiid’s benching meant to balance Tatum’s? Tatum, for his part, got the ball early, and turned it over; his first shot of the game hit the side of the backboard. A friend of mine, a Celtics fan, texted me that Tatum should forget the mind games, leave the arena, get on a plane, and go home. In its final game in pool play, on Saturday, the United States blew out Puerto Rico, with another balanced attack—largely led by the bench.

After the South Sudan game, Tatum talked about being benched. He called it “humbling,” adding, “You can be frustrated that you want to play as a competitor but maybe have some empathy for some of the guys on my team”—the Celtics—“that don’t always get to play or play spot minutes.” He seemed affected, but he did not seem eaten alive by disrespect. He did not lack empathy. He did not seem like a bad person. There are people who think that’s a problem—who think that Tatum lacks a killer instinct, that he fails to seize his glory. People sometimes forget that the Dream Team also made playing-time adjustments throughout its run, using six different starting lineups in six games. The only player to start every game was Jordan. ♦