You go to the store for a carton of milk or, if we focus on our industry, a new item of clothing. You pay the market or retail price based on what it costs to produce and sell that item.

But did you know that you don’t always pay the “true price”? Manufacturers and companies don’t usually pass on all the costs to the end consumer. Just think about the impact the production of our items has on our environment, like raw material consumption and the carbon emissions from transportation, for example.

This background story is about True Pricing, a concept invented by social enterprise True Price. We spoke with Rob Hofland, the group chairman of the Dutch political party D66 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, who submitted an initiative proposal for True Pricing for municipal tenders last January 11.

We take a look at what True Pricing could mean for the fashion industry halfway through the article and discuss to what extent the fashion industry is already working towards fairer pricing for all..

The idea behind true pricing is to highlight that most prices of goods and services do not reflect the full cost.

“There are ‘hidden costs’ in many of the products that we buy that are not reflected in the final retail price,” begins Hofland.

Hidden costs is the term used for non-visible costs associated with the production of the items and may include external aspects such as environmental pollution, depletion of natural resources, or social costs such as forced labor or violations of workers’ rights.

A product may appear cheap to the consumer but could cause siegnificant environmental damage or be produced under poor working conditions.

.

“Many (environmentally polluting) products have a low price, but those prices are artificially low,” Hofland explains. “And low prices have many negative effects. For example, they stimulate consumption behavior, one of the things that has led to the current climate crisis.”

And there’s more…

“Those hidden costs are always present and often still have to be paid,” the politician explains. “It is usually the taxpayer who pays for the non-visible costs, and that taxpayer is the one who buys the product.” By that, Hofland means that consumers like you and me usually pay for the hidden costs through taxes or other social costs.

Change Inc, a sustainable news platform, gives a concrete example in a video about True Pricing: “Take company A. This company discharges waste into a river. This is not a big deal and is essentially allowed, but a town downstream depends on the river for drinking water. That town now needs to build a water treatment plant. The cost of this, through taxation, is borne by the town’s residents, when in fact it should have come to company A.”

2. What are the benefits of True Pricing? What might the introduction of True Pricing mean? What would True Pricing change from the current system?

“If in reality the more sustainable option is also the cheapest option for society, then it should also have the lowest price in the store,

argues Hofland.

“Constantly morally appealing to the individual to buy responsibly, I’m done with that,” Hofland proclaims. “Because, as a consumer, when I find myself on the high street, I simply don’t know what the best choice is. Take a clothing store, for example. Usually, good staff can provide me with some information, but I don’t have a clue myself.”

“Moreover, entrepreneurs who make more sustainable products are not rewarded,” Hofland continues, “because their products are usually more expensive (than cheaper producers who tend to be more polluting) due to the efforts of responsible production.”

In addition, local entrepreneurs are often losing out to foreign products when it comes to competing on price, the politician says, because climate costs, for example, are not taken into account.

This is why Hofland is advocating for a systemic change.

By making the true cost of products visible, companies that do good for the environment and society will become more competitive compared to the less sustainable alternatives. This way, companies/manufacturers will be encouraged to be more sustainable. At the same time, ‘real prices’ will also make it easier for consumers to make a fair trade-off and make conscious choices when shopping.

Did you know that the founder of the concept of True Pricing is the Dutch social enterprise True Price?

True Price is an organization founded in 2012, whose mission statement is ‘to realize sustainable products that are affordable to all by enabling consumers to see and voluntarily pay the true price of products they buy,’ according to its website. True Price has developed the True Pricing method to calculate the real price of products and services. This method is publicly available.

The Impact Institute was founded in 2019 as a ‘spin-off’ of True Price (more on that later).

3. How would True Pricing work in practice? How can True Pricing actually be successful?”

“First of all, one needs to identify what the real costs per product are,” Hofland explains. In a nutshell, this is the formula of True Pricing: market price + hidden costs = the true price.

“But in order to map out those ‘hidden costs,’ the entire supply chain has to be scrutinized.” Finding/uncovering all that information is probably one of the biggest challenges of True Pricing.

In 2023, Dutch supermarket chain Albert Heijn tested a “true price” for a cup of coffee at its “to-go” stores. In the supermarket chain’s report on the experiment, Albert Heijn said that it “was able to map much of the overall impact of coffee, but some elements had not been calculated due to the lack of reliable data and information.”

Step two would be to start paying the real price as well, states Hofland.

.

4. What does the City of Amsterdam’s True Pricing initiative proposal exactly entail?

“In politics, we discuss sustainability a lot, but the solutions and innovations for a more sustainable future come from businesses and residents, not from officials,” Hofland argues. “Those solutions are also already there (in part), but if you make it unattractive for entrepreneurs to do business in a responsible way, then, of course, it won’t happen.”

“When the municipality considers the actual costs in purchasing

(the so-called municipal procurement or tenders), and the concept of True Pricing becomes implemented on a larger scale in the future, then it will become interesting for entrepreneurs to make products and services you purchase as a government in a sustainable way.”

“The municipality is buying in 2 billion euros, so that can be a serious incentive,” states Hofland.

.

“In addition, you have a duty as a government to set a good example through regulation, but also through your own purchasing,” the politician believes.

5. What could True Pricing mean for the fashion industry?

“I think True Pricing can ensure that we choose clothes with love again so that shopping becomes a more conscious and enjoyable process. True Pricing will encourage consumers to shop more sustainably and ensure that more attention is paid to such things as the provenance and longevity of products,” Hofland says.

And True Pricing – as in other sectors – will be able to bring about fairer competition, the Amsterdam D66 graduate believes. Fast fashion is now fast fashion the cheapest, but often also the most polluting. “You want to give the entrepreneurs who have a more unique product than a 5 euro T-shirt’ another chance to compete with such companies,” Hofland notes.

“An important part of True Pricing is also demonstrating that we can buy clothing at such unnaturally low prices,” says Leanne Heuberger, Sustainable Value Chains Advisor at Impact Institute (see box 2, ed.), ‘because the actual costs of those same fashion items are paid elsewhere in the world.’ “Think of people working for very low wages or in unhealthy and unsafe working conditions.”

Background: The Impact Institute helps organizations, including textile companies, calculate their impact based on the real costs to society

“Where True Price focuses on the impact of products in order to inform consumers, Impact Institute was founded to support organizations with impact management,” says Heuberger. “We use the True Pricing methodology to give companies, including textile companies, insights into the environmental and social impact throughout their entire value chain.” Companies use this knowledge for better and more sustainable decision-making at the highest level, she explains. “We also support them in the transition to business operations that respect the boundaries of our planet and human rights.

The advisor reports that a lot of information is available for determining the environmental impact.

“Consider where and how products are made, which materials (such as cotton or polyester) are used, and the processing methods.” Mapping social costs is more complex due to long and non-transparent supply chains. “Fashion and textile companies often have insight into their direct partners (read: suppliers and manufacturers), but the further back you go in the chain, the more difficult the information is to retrieve,” says Heuberger.

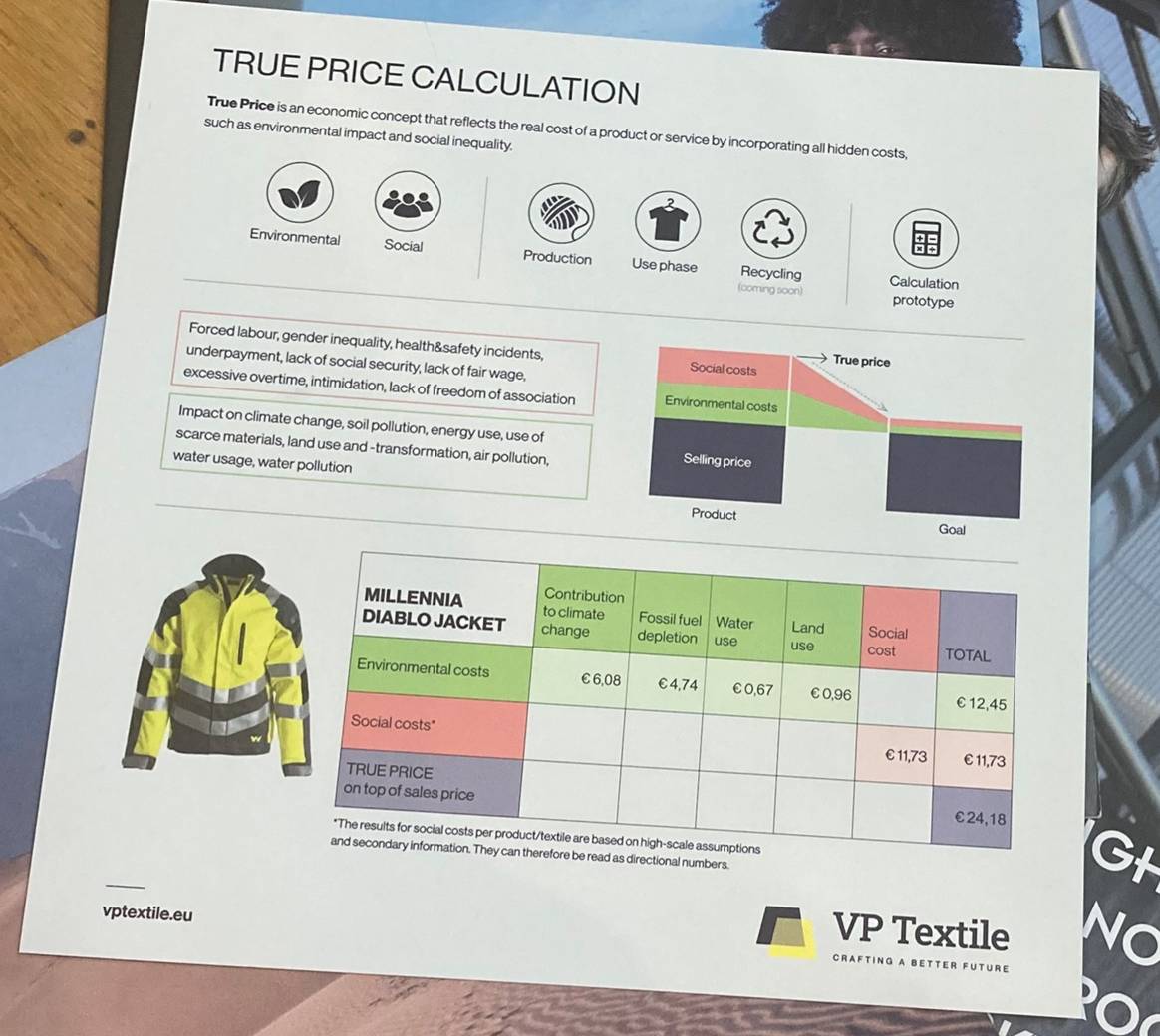

One of the major challenges remains achieving transparency throughout the entire supply chain, notes Els de Ridder, head of sustainability at VP Textile, a textile company that owns the Van Heurck, Hydrowear/Texowear, and HAVEP Workwear brands, that collaborates with Impact Institute. “The True Pricing method does force us to uncover and mitigate that transparency and any pain points (read: improve things, ed.).”

VP Textile has been working on impact and true pricing for some time now. The company publicly communicated about this for the first time at A+A, a Düsseldorf trade fair for personal protective equipment. To provide more insight into true prices, VP Textile has developed a prototype calculator to better explain to customers why one product, for example, is five euros more expensive than another, says De Ridder. “With this calculator, we compare the True Price against a benchmark product. Consider, for example, recycled fabric vs virgin (new) materials.” Although not everything can be benchmarked at this point. “We would also be able to make better comparisons when, say, twenty other companies also measure the environmental and social costs.”

Nevertheless, the first reactions were very positive. “Customers found it very concrete to have complete insight into environmental costs and social costs,” notes De Ridder. “But we’re not there yet,” she adds cheerfully. “Identifying and reducing impact is an ongoing process. Ultimately, we strive for minimal environmental and social costs.”

6. Doesn’t True Pricing mean that everything would become more expensive?

“No,” says Hofland. “Ultimately, of course, it’s simply a market principle that works. Incentives are created that make the sustainable option cheaper.”

“Maybe the cheapest option will be slightly more expensive than the cheapest fast fashion T-shirt of this moment,” he continues. “But then it will be a more sustainable and a better product all around. If that T-shirt lasts longer than the aforementioned fast fashion garment, it will come out cheaper per wear.”

Is the consumer actually prepared to pay the True Price?

Albert Heijn reported that some of the consumers who took part in the coffee experiment were prepared to pay the true price. Moreover, a Dutch study looking at consumer reactions to True Pricing in food products, conducted among over a thousand people in 2021, showed that there is support for knowing the true price. However, some consumers indicated they wanted more information about where the money goes. Although showing the true price had little influence on overall choice behavior, the study found that consumers were likely to choose cheaper options if only a part of a product group had a true price.

Last summer, German supermarket discount chain Penny calculated and charged the true price of nine products in more than two thousand branches for a week. The true pricing project increased awareness and discussion about the environmental costs of production and consumption. Within Penny’s customer base, there was an increased interest in greener or more sustainable products, as the company announced on January 24. However, the (mandatory!) higher prices sometimes had a dampening effect on overall demand. The main reason customers did not buy the products was the price. Penny pointed out the so-called ‘intention and behavior gap.’ There is a bridge between supporting environmentally friendly initiatives in theory and consumers’ actual purchasing behavior when it has financial consequences. But that is not very remarkable, NRC noted in a newspaper article about the test results, ‘since low prices are one of the main reasons customers shop at discounters like Penny.’

“The key takeaway is that when the True Price is calculated for polluting products, it is just as essential that there is a good alternative available for purchase: an affordable product that is produced more sustainably,” emphasizes Heuberger.

The last part is no longer a thing of the future, according to her. “Passing on part of the hidden costs, for which we will sooner or later be presented with the bill, is becoming increasingly realistic. For example, the recently adopted CSRD legislation requires larger or ‘high-risk’ companies to report damage to people and the environment in their supply chain,” illustrates Heuberger. “This development promotes a trend whereby companies are evaluated not only on financial performance but also on non-financial aspects. It will strengthen the position of companies with a sustainable business model, and this, in turn, will be reflected in stores: in the long term, sustainable products will become cheaper than products with a high social and/or environmental impact,” states Heuberger from Impact Institute.

7. Finally, what will happen next with the municipal proposal?

“We’re waiting for the administrative response from the municipality,” says Hofland. “If the municipality agrees, it will then be discussed in a council committee. Then, the city council must then vote on it.” Hofland is optimistic about the outcome. “So far all my proposals have been accepted,” he says cheerfully.

“I think True Pricing will be very normal in ten or twenty years,” concludes Hofland. “Because the current system is sometimes simply skewed. If I fill up the gas tank in my Fiat Panda, I pay more tax than if you took a plane to the other side of the world for a holiday,” he illustrates. “Ultimately, we must ensure that what is inexpensive for our society is priced low and what is expensive is priced high.”

Sources:

– Interview with Rob Hofland, faction leader D66 Amsterdam, on January 22, 2024.

– Interview with Leanne Heuberger, Sr. Associate of the Impact Institute, a sister organization of True Price, on January 25, 2024.

– Interview with Els de Ridder, Sustainability Manager at VP Textile, on January 29, 2024.

– Change Inc. video ‘How can I do business sustainably? | True Pricing’ was published on YouTube on June 17, 2014.

– The True Price website was accessed on January 2024.

– Ah.nl tab True-Price and specifically the pages ‘First phase true price experiment Albert Heijn to go completed’ & True pricing experiment at Albert Heijn Fact sheet calculations, from April 2023, consulted on January 2024.

– Impact Institute & ABN Amro report ‘The hidden costs of jeans True Pricing in the jeans supply chain,’ published in May 2019.

– Final report on project ‘True Pricing and Consumer Behavior,’ by Consortium partners Centerdata, Behavioral Insights Netherlands, Wageningen Economic Research, and Amsterdam UMC, subsidized by the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature, and Food Quality, dated December 2, 2021.

– Press release ‘University of Greifswald and TH Nuremberg present an evaluation of the Penny project “True Costs 2023”’, from the Rewe Group, published on January 23, 2024.

– Press release ‘Environmental costs: campaign week on ‘real costs’ as a basis for a ground-breaking study across Europe,’ from the Rewe Group, published on July 31, 2023.

– NRC article ‘At the checkout, the wallet wins over the greener choice,’ by Joost Pijpker, from January 24, 2024.

– Some parts of this article text were generated using an artificial intelligence (AI) tool and then edited.