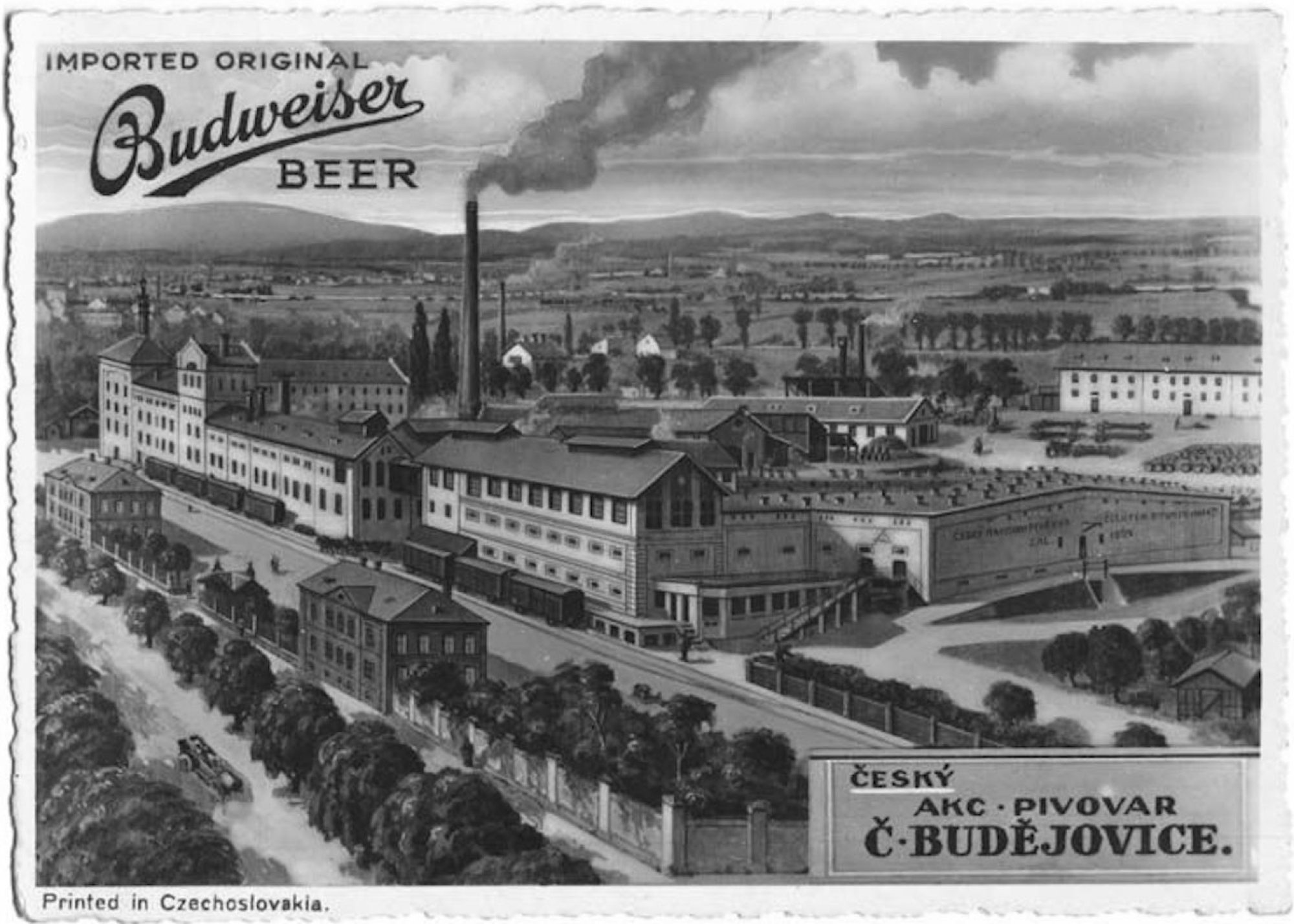

After all, the makers of this beer in the south of the Czech Republic have some awkward history with Americans. More than a century of it, to be precise, centred on an intellectual property battle believed to be the world’s longest-running trademark dispute.

The legal fight is now in its 127th year and revolves around the right to use the name Budweiser.

Budweiser Budvar beer is named after Budweis – the Austro-Hungarian empire-era name of its hometown, Ceske Budejovice, where variations of the beer have been brewed since the 13th century.

The drink produced using water from the town’s 300-metre (984ft) deep springs was soon known colloquially as the Beer of Kings.

In the same way that Pilsner lager comes from nearby Pilsner and Erdinger comes from Erding, in Germany, Budweiser is from Budweis. Or at least it was until the 1870s, when Adolphus Busch began producing Budweiser 5,000 miles (8,000km) away, in St Louis, Missouri in the United States.

Busch emigrated to America from Wiesbaden, in Germany, and seems to have used the Budweiser name because he liked the Czech beer and believed it would appeal to thirsty, homesick European migrants in the US. He even had the bottle to subvert its nickname and call his product the King of Beers.

By pioneering pasteurisation, bottling and refrigerated train cars, Busch and his partners soon turned Budweiser into America’s first nationally sold beer. Today, it is the world’s second best selling beer (behind China’s Snow brand).

Order a Budweiser in Hong Kong or in almost any bar anywhere in the world and the chances are you will be served a bottle or a pint of the US brand, which outsells Budweiser Budvar globally by a ratio of around 35 to one.

Even in Asia, it regularly clocks up higher sales than regional favourites such as Asahi, Tiger and Tsingtao.

Small wonder, then, that the modern-day US company Anheuser-Busch is determined to do all it can to hold on to the Budweiser name, or that it has pockets deep enough to continue to defy what appears to be natural justice and fight a seemingly endless trademark battle.

More than 300 separate legal actions have been lodged against the brewing monolith by the Czech minnow since 1907 in what representatives of Budvar say is a matter of national pride.

“When you look at the size of [Anheuser-Busch], we are a drop in the ocean,” brand ambassador Radim Zvanovec told the UK’s Beer Fridge podcast in February.

Nevertheless, Budvar has scored some notable triumphs. While Anheuser-Busch maintains the rights to the Budweiser brand in the US (where Budweiser Budvar is labelled Czechvar), the Czech brewery now owns the rights to the Budweiser name in most of Europe, where the US brewer has been forced to rebrand its beer as Bud.

Separate legal fights have been fought in scores of jurisdictions, something Budvar can surely only manage as a national, government-owned entity rather than being answerable to shareholders.

Budvar won exclusive control over the Budweiser brand in Germany in 2009, for instance, while in the UK, courts have ruled that neither company can claim exclusive rights to the Budweiser brand.

In a landmark victory in Italy last year, however, the Court of Appeal gave the Czech brewery the right to sell its beer there as Budweiser, overturning a 20-year ban on it using the name.

The legal battlefield has now shifted to Africa, where the two beer companies are competing for the Budweiser name in countries including Nigeria, Kenya and Tanzania.

Away from the international law courts, meanwhile, Budweiser Budvar is playing its part in a healthy growth in beer tourism. Between 50,000 and 60,000 people a year now pay around €10 (US$10.65) each to visit the Budvar brewery.

The Pilsner Urquell brewery, in Pilsner, and Staropramen brewery, in Prague, also run tours, offering connoisseurs the chance to indulge in a leisurely, zig-zaggy triangular brewery crawl through the Czech Republic, with copious glasses of freshly brewed beer along the way, provided they can find a designated driver.

Czech people consider Budvar the real and only Budweiser … they obviously prefer Budvar

The beer tour at Budweiser Budvar makes for a diverting hour, but is hardly captivating enough in itself to justify a return ticket. (Disappointingly, there is no Wonka-style beer river and no everlasting glasses of lager, either.)

The brewery stands in a residential area within staggering distance of the centre of Ceske Budejovice and behind a gleaming modern glass-fronted visitor hub featuring a hipster-friendly bar, a display of old photos and adverts, and a museum and souvenir shop.

The tour takes visitors through vast rooms filled with giant copper vessels, past a gleaming production line and into a chilly cellar where the temperature is kept at a constant two degrees Celsius (35.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and beer is stored in tanks the size of mini submarines.

It is here visitors that are served frothing mugs of beer fresh from the brewery tank.

All things considered, though, the best places to enjoy Budweiser Budvar are the cosy bars and restaurants dotted around the sleepy historic centre of Ceske Budejovice, where it is delivered by waiting staff circling constantly with trays full of frothing draught beer along with gigantic plates of pork, dumplings and sauerkraut.

This is the country that calls itself the Republic of Beer, and with good reason. Czechs drink more beer than anyone else in the world, with surveys claiming an annual per capita consumption of around 300 pints.

To put it into perspective, that is 40 per cent more beer than the second biggest drinkers in the world, the Austrians, and seven times more beer than people in Hong Kong drink.

Although its price has risen sharply over the past decade, beer remains relatively cheap here, at less than €2 a pint. Above all, almost all of it is locally produced.

Only 1 per cent of beer served in the Czech Republic is imported; so in Ceske Budejovice you will find only the Beer of Kings and not the King of Beers.

“Czech people consider Budvar the real and only Budweiser,” says Budweiser Budvar communications manager Barbora Poviserova. “They are well aware of the big taste difference between our beer and US Budweiser, and they obviously prefer Budvar.

“It is definitely a matter of local pride, but they do not feel angry about it. Czech people consider US beer irrelevant.”

I’ll drink to that.