But Kao copied much more than just New Order.

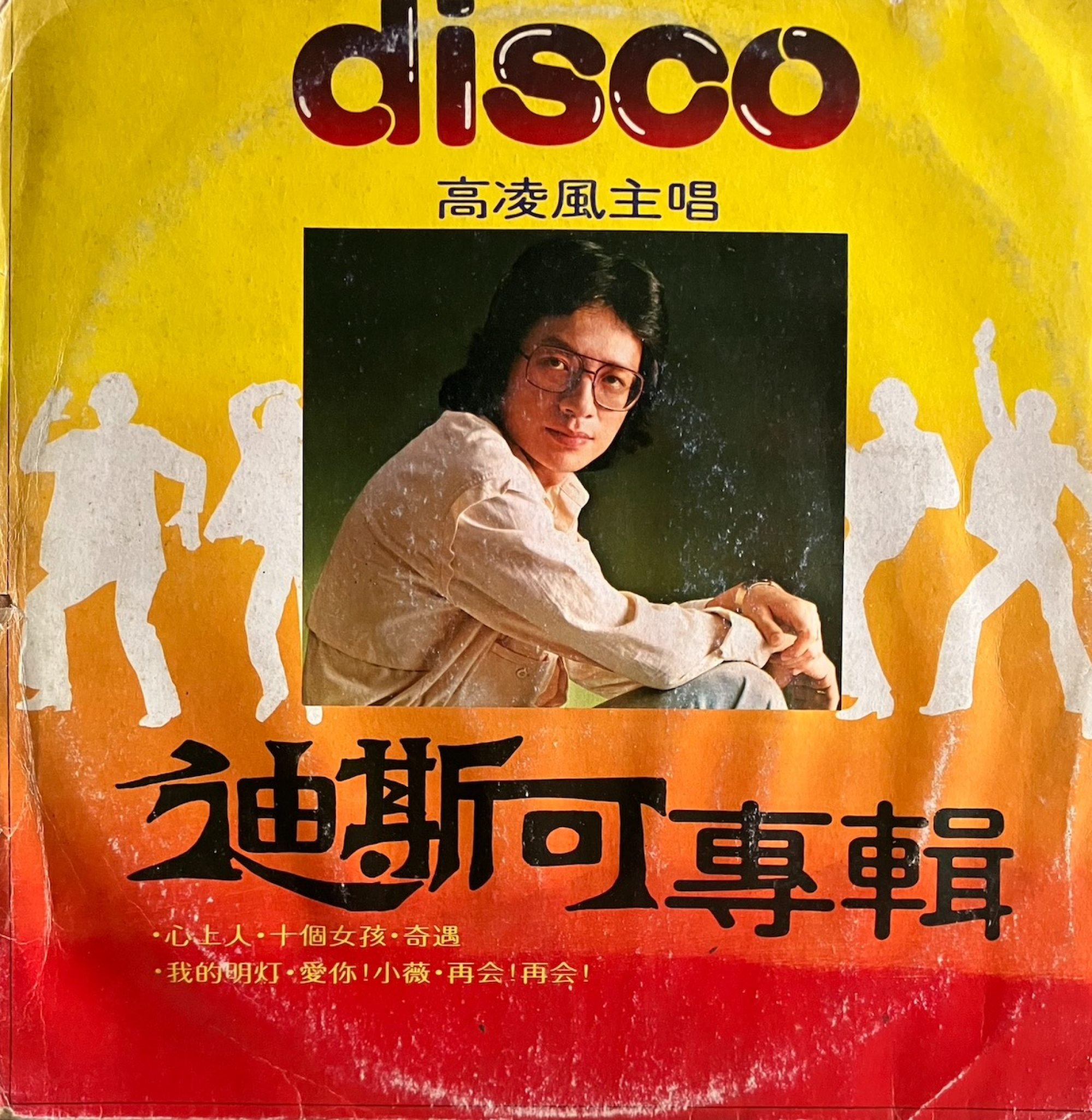

On just a single album from 1980, its cover emblazoned with the English word “disco”, he produced Chinese versions of Barry Manilow’s “Copacabana”, Anita Ward’s “Ring My Bell”, Rod Stewart’s “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?”, Blondie’s “Call Me” and Boney M.’s “Gotta Go Home”.

1980s Japan lives on in Hong Kong as ‘future funk’ music finds a home

1980s Japan lives on in Hong Kong as ‘future funk’ music finds a home

They have now converged on a loose collection of Mandarin music that looks like it might be a missing link to some previously undiscovered dance age in Taiwan’s past.

For most young Taiwanese encountering these songs for the first time, the reaction is wonderment.

Yuki Liu, the 28-year-old author of a recent article in the Taipei music magazine YSO Life, headlined “Frankie Kao covered New Order and David Bowie!?”, explained that in her eyes, Kao has recently transformed from “tacky and unsophisticated” to “trendy, cool and avant-garde”.

Kao’s disco tracks – and there are scores of them – are, however, pieces that don’t fit neatly into the standard puzzle of Mandarin music.

Why don’t you sing your own songs? Let’s sing our own songs!

Folk singer Li Shuang-ze’s exhortation for an alternative to pop sung in English

Even a few years ago, Taiwan was not imagined to have had its own disco era. But now that songs are being unearthed, uploaded and added to playlists, Taiwan’s music nerds are beginning to wonder, did disco – somehow in the midst of Taiwan’s martial-law era – also exist as a cultural milieu?

Unfortunately, owing to the fast, cheap and chaotic nature of Taiwan’s music industry at the time, documentation is patchy. Recordings almost never included liner notes and rarely listed musical credits beyond the name of the singer. For many of those singers, no biographies exist.

So while social media has given us a sudden profusion of songs and videos, it has at the same time given us almost zero historical context in which to place them. But as more and more people look into these questions, they are finding some surprising answers.

Among them, that Taiwan disco, by its very existence, may have the potential to alter the history of Mandarin pop.

Over the past several decades a more-or-less official history of Mandopop has emerged, which traces the genre’s roots back to one seminal moment in 1976.

At a small concert at Tamkang College of Arts and Sciences, in north Taiwan, folk singer Li Shuang-ze took the stage holding a bottle of Coca-Cola and said, “Young people around the world are drinking Coca-Cola and singing songs that are in English.”

He then smashed the bottle and exhorted his fellow singers, “Why don’t you sing your own songs? Let’s sing our own songs!”

Li’s charge to “sing our own songs” became a cornerstone of Taiwan’s “campus folk movement”, which swept the island in the late 70s and early 80s, and influenced other Chinese folk movements in Singapore and Hong Kong.

In the 90s, on the strength of this accumulating star power, Taiwan surpassed Hong Kong to become the world’s top producer of Chinese music. Now with more than a billion fans, Taiwan-made Mandopop has developed into one of the biggest music industries on Earth.

Young fans of Hong Kong’s Cantopop legends keep playing the old songs

Young fans of Hong Kong’s Cantopop legends keep playing the old songs

But this narrative has little room for Kao’s disco covers, nor the incredible amount of music copying that took place in Taiwan up until the mid-80s.

If you happened to set foot in Taiwan in 1980, it was awash in Western music. In the 70s, Taiwan emerged as one of Asia’s top music pirates, pressing 350,000 pirated vinyl records a month, including huge swathes of Western music catalogues, most for domestic consumption.

In Taipei’s nightclubs, live bands filled their repertoires almost exclusively with Billboard Top-40 hits of the time.

A few Taiwanese scholars have lately begun to say they can no longer deny the influence of Western pop – once known locally as re men yin yue, or “hot music” – on the development of Mandopop.

According to them, it’s like crowning Elvis as the king of rock ’n’ roll but without ever admitting that he was influenced by gospel or the blues – which makes a figure such as Kao all the more interesting.

Kao was born Ge Yuan-cheng, in 1950, in a Chinese Nationalist military village in Kaohsiung. While playing in a rock band in college, he managed to catch the ear of mainland China-born songwriter Qiong Yao, who in 1974 wrote a minor hit for him that launched his career.

The song was part of a movie soundtrack, and he took the name of the film’s hero as his new stage name – Frankie Kao, or Kao Ling-feng in Chinese.

By the time he had turned 30, Kao had established himself as a sort of Taiwanese Barry Manilow, a brilliant showman and comedian, most at home in front of television cameras on glitzy stage sets, framed by slinky show-dancers.

By the standards of the time, Kao was also a fairly brazen playboy, and one with a shady side. He lost huge sums gambling in illegal dens – which he boasted about publicly – and in 1984 served three months in jail for carrying a concealed revolver to a nightclub performance.

For most Taiwanese, Frankie Kao’s version was the original

Han Hsien-guang on the singer’s take on Anita Ward’s ‘Ring My Bell’

Personal firearms were, and still are, illegal in Taiwan, but Kao later explained the action, saying the nightclubs were crawling with gangsters and, “I feared for my personal safety.”

Though Kao’s fame stemmed mainly from his performances on television variety shows and in nightclubs, he recorded at least 27 studio albums, and while the music in these songs always resembled the Western original, the Chinese lyrics took on new meanings.

Disco’s themes of sexual liberation were sanitised in the Chinese versions, whose lyrics had to pass Taiwan’s government censors. Ward’s “Ring My Bell”, for example, which many believed to be a euphemism for inviting a man to bring her to orgasm, is changed in Kao’s version to an innocuous “Ringing of the School Bell”.

“The twist Kao added was to translate the lyrics to Mandarin, and by doing that he reached a whole new public,” says Han Hsien-guang, a music producer who worked with Kao promoting concerts from the 90s onwards.

“People in central Taiwan who saw him on TV had no idea who the original singer was or that the song was even copied. For most Taiwanese, Frankie Kao’s version was the original.”

In Taiwan, musicians referred to these songs using the English term “copy songs”, while the general public came to know them as kou shui ge, “saliva songs” – the implication being that saliva is cheap and lacks the substance of real speech or real singing.

This kind of copying was possible, says Han, “because there was no copyright, international publishing hadn’t come in Taiwan yet. We didn’t pay any royalties.”

Taiwan only began to enforce music copyrights from the mid-80s, spurred on by threats of Special 301 economic sanctions from the United States and a new push from Taiwan’s domestic music industry, which was seeing its own profits cannibalised.

The island’s most visible anti-piracy campaign was launched in late 1985, behind the anthem “Tomorrow Will Be Better”, which, sung by a chorus of Taiwan’s 60 top pop stars, was, ironically, a bald-faced imitation of “We Are the World”.

For Chinese people, music is treated as literature. If you ask someone why they like a song, they will say it’s the lyrics

Hsieh Chi-pin on why Taiwan’s disco era was ephemeral

Though Kao may have built his career as a copycat, young people now find him exciting because he was one of the first to combine Mandarin music with dance beats and develop a vocal style that kept pace. While most Chinese stars sang from the diaphragm like Frank Sinatra, Kao sang from the hips like Elvis.

Yet, at the time, “dance music was considered low-grade music”, explains Taiwanese musicologist Hsieh Chi-pin. “People didn’t care who was singing and the music wasn’t taken seriously.”

Dancing was also illegal in Taiwan. A 1957 law called the Regulations for Restricting Dance Venues in Taiwan Province during the Era of Turmoil limited dancing to US military bases and international hotels. Though enforcement loosened in the years before martial law was rescinded, in 1987, Kao’s televised image of disco was in stark contrast to the social reality.

“For Chinese people, music is treated as literature,” says Hsieh. “If you ask someone why they like a song, they will say it’s the lyrics. In our culture, there’s a major emphasis on the lyrics, but never the riff or the intro or the hook. For this reason, only love ballads were considered to be serious music.”

This is one reason, adds Han, why “Kao’s songs didn’t have a lasting life”.

As the 80s drew to a close, Kao, who had hitched himself to disco’s fleeting trend, saw his fame quickly erode and he became embroiled in disputes with TV stations, and investments in a string of failed nightclubs.

Though the Frog Prince continued to appear on television in subsequent decades, in 2012, he was diagnosed with leukaemia and he died two years later. He was 63.

The rediscovery of Taiwan’s disco era began rather suddenly, in the years just before Covid-19 hit.

Academic discussions were organised with titles such as “Did Taiwan really have a Disco Era?” Obscure 70s recordings began appearing in YouTube videos with titles like “Chinese funk pop” or “synth disco” (most notably on a 2019-created channel called Ultradiskopanorama), and in 2020, a hot-selling vinyl compilation appeared under the title, “Taiwan Disco: Disco Divas, Funky Queens and Glam Ladies From Taiwan in the 70s and Early 80s”.

Taiwanese rapper-turned-anthropology professor Fernando Lin Hao-li is one of a handful of scholars now studying Taiwanese disco, and he recalls a collective eureka moment of his hip hop clique from 2003.

They had just encountered a mixtape of 70s Korean funk and soul by South Korea’s DJ Soulscape, most of it produced by local bands who played in the East Asian country’s US military bases during the Vietnam war era.

In an article published last year, Lin wrote, “We began to ask ourselves, did Taiwan also have these kinds of works from the 1970s and 1980s? After all, hip hop has a close ancestral relationship with disco, funk and soul.

Perhaps Taiwanese hip hop also has some musical precursor that has not yet been carefully explored. Was there anything in our past we could compare to Motown? To the sound of black music? Did we have our own disco era?”

In 2021, Lin received a grant from Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council to study the island’s musical past. So far he has collected more than 200 Mandarin pop songs with funk, soul or disco beats and interviewed musicians and producers going back to the 60s.

He has also begun charting the emergence of Taiwan’s discotheque culture, from illegal underground discos, which became popular during the early 80s – their business licences were sometimes registered as “dance schools” – to Taiwan’s first legal disco, Kiss La Bocca, a 2,000-person-capacity venue that opened in 1986 in Taipei’s Magnolia Hotel.

What Lin discovered was that Taiwan disco did, in various senses, exist, but it was characterised by a series of disconnects.

The “saliva songs” released on records never became radio hits. They were instead blasted mainly in night markets, where they were also sold cheaply on cassette tapes and occasionally on vinyl.

Moreover, he says, “Taiwan’s self-produced disco songs” – such as Kao’s – “never played in actual discotheques”, which only spun Western pop and attracted crowds of mainly urban, nouveau-riche youths.

But again, there was a chasm between the authentic Western disco consumed by urbanites in illegal discos and pirate records and the adapted, localised versions presented by figures such as Kao on TV stations and radio. “This has been completely omitted from our pop music history,” says Lin.

After 10 brilliant seconds the vocals come in and the vibe evaporates. Suddenly it sounds like just another old-timey Chinese pop song

Fernando Lin Hao-li on the disconnects in some 80s Taiwanese pop music tracks

“There are cultural reasons behind this,” explains musicologist Hsieh, who is one of the biggest music nerds this writer has ever met. A 50-year-old jazz violinist who studied for six years at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, in Belgium, as a hobby, he charts out musical notation to show how some songs are derived from others, mapping out beats, basslines, keys, time signatures and chord progressions.

He currently offers a 10-part lecture series on pop music influences, with two full lectures devoted to city pop, a genre of light, synth-driven Japanese pop from the early 80s that re-emerged around 2018 and is now worshipped by millennials the world over.

“The kids think it’s really fresh, but actually it’s a study of American pop R&B,” says Hsieh. To prove this, he curated a YouTube playlist of 123 songs to identify city pop’s extensive borrowings, starting with the genre’s defining track, Mariya Takeuchi’s “Plastic Love” (1984), which he insists lifts its bassline directly from Bill Withers’ “Lovely Day” (1977).

“I don’t mean to smash your face,” he says, “but I want to tell young people about the influences behind the music. This is very, very important.”

In Taiwan, “the young generation followed a trail from city pop – and I don’t know if this was going backwards or sideways – but they traced it to Taiwan’s disco era”, says Hsieh. “Basically, they were wondering if Taiwan had something similar buried in its pop music history. So they began to search.”

What they discovered was music that, as Lin describes it, was full of disconnects.

Of the hundreds of songs he has identified, Lin says, “It’s hard to find a complete danceable track. You often find a song with a great funk intro, maybe it sounds like something from Curtis Mayfield or Isaac Hayes, but after 10 brilliant seconds the vocals come in and the vibe evaporates. Suddenly it sounds like just another old-timey Chinese pop song.”

Hsieh agrees. “If you are talking about mainstream Chinese music, disco and funk were only ever smuggled in. Maybe the musicians were exposed to those genres and wanted to play it, but the record companies weren’t ready for it. So you just get bits and pieces.

“Moreover, in the recording studios they tended to turn down the bass, drums and rhythm section. Their whole focus was on the lyrics, the vocals and the melody.”

In this scenario, Kao, who fully embraced everything about disco, including its basslines and four-on-the-floor beats, stands out from almost every other artist of his generation. But what was Kao’s process in the recording studio?

In studying a dozen or so of Kao’s records, only one lists any musical credits. It also happens to be the record featuring that “Blue Monday” cover.

Shown the list of musicians on the album, Hsieh pauses before announcing, “Oh, I know him.” He points a finger at the name of drummer Rich Huang. “I met him in the studio one time. Let me give him a call.”

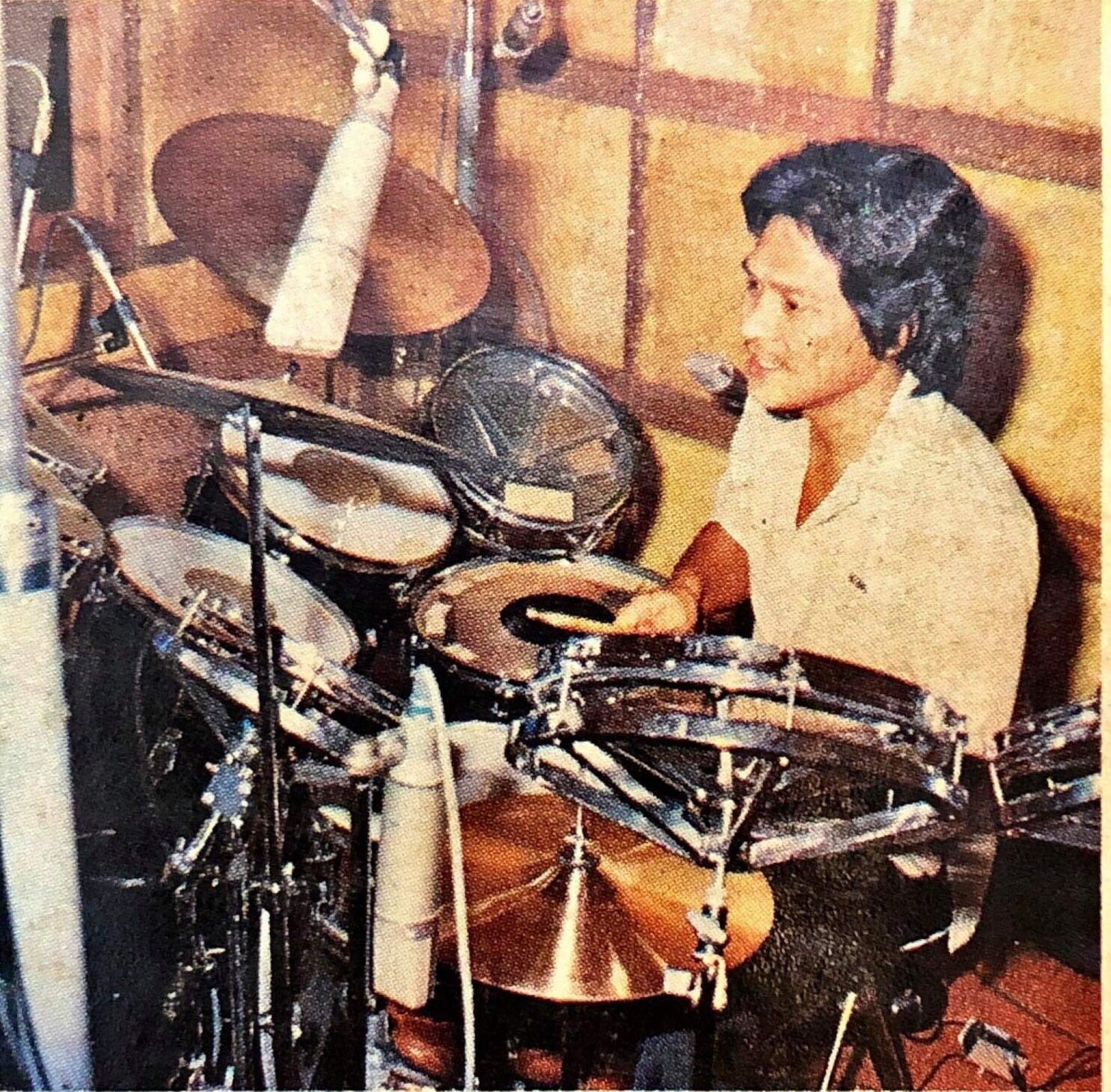

Before I meet Rich Huang Rui-feng, he has been presaged by his reputation as Taiwan’s “king of drums”, a musician who at the age of 74 has received multiple lifetime achievement awards and come to be venerated with special programmes in the august chambers of Taiwan’s National Concert Hall, a shrine to music presumed to be elevated and removed from the simple throbbing passions of pop.

Yet pop music was part and parcel of Huang’s career, and his discography is so voluminous it may never be properly calculated. His website, which he compiles himself the way some collect stamps or plot out family trees, lists nearly 300 singers and groups with whom he has recorded, including pretty much every famous Taiwanese singer from the 70s to the 90s, which is also the golden age of Mandopop.

Coco Lee never wanted to be a star, ‘I was shy’ – from the archive

Coco Lee never wanted to be a star, ‘I was shy’ – from the archive

While setting up the interview with Huang’s daughter, she casually mentions his recordings totalled “more than 10,000” or sometimes “tens of thousands”. At first I discounted this as a figure of speech – in Chinese, “10,000” generally just refers to a big number, as in the saying, “May you live 10,000 years”.

But the figure was repeated so often by both Huang and his daughter that later I began to wonder if it could possibly be correct. Let’s say Huang worked five days a week, recording 10 songs a day. At this theoretical yet ridiculously prolific pace, it would be possible for Huang to record 10,000 songs in four years’ time. It was after my interview with Huang that these figures began to sound plausible.

“If we went into the studio to record an album at 1pm, we’d be finished in time for dinner,” recalls Huang. “We could record up to three albums a day. There were no rehearsals. We’d get the arrangements when we got to the studio. Sometimes when we walked in, the arranger would still be writing out notation.”

It was perhaps only possible because Huang and the other studio musicians had been trained in nightclubs to play repertoires of thousands of songs on demand.

Huang, a native of Kaohsiung, failed junior high, and so at the age of 14 became a “band boy”, fetching drinks and carrying instruments in one of Taipei’s dance halls. They were big bands, and the dance halls were old-style taxi dance places similar to the Shanghai clubs of the 1930s, where rich businessmen paid young hostesses to dance with them.

At 17, Huang was finally allowed to don a dinner jacket and bow tie and take a seat behind the drum kit. The band’s repertoire was contained in multiple phone book-sized binders colour-coded according to the rhythm: blues, cha-cha, rumba, swing.

He cut his teeth on the nightclub stage, sometimes belting out a polka when he should’ve been playing a different rhythm. But he kept his head down when patrons complained, “Why do you have a kid back there playing drums?”

Not long after, he was discovered by Tony Ong Ching-hsi, a bandleader who would go on to become a leviathan in Taiwan’s recording industry, and is now being recognised, as Huang points out, as “the only one who could do notation for a horn section”.

Ong was a prolific record producer in the 70s and 80s, and scholars such as Lin are now beginning to recognise him as a pioneer in introducing the sounds of Motown and American soul and funk to Taiwanese pop.

In 1968 or 1969, Ong invited Huang to join a house band at the US military’s Ching Chuan Kang (CCK) Air Base near the city of Taichung. At the height of the Vietnam war, the base housed around 5,000 US servicemen and, though mainly a support facility, it also launched combat missions of B52 bombers on raids over North Vietnam and Cambodia.

If you play this song for Taiwanese people, many won’t know it’s Western music. They think it’s from a puppet show

Hsieh Chi-pin

Huang now laughs that he couldn’t speak any English – “I couldn’t understand a thing!” – but CCK provided his first education in Western pop. He studiously learned the latest hits by taking notation while listening to songs over and over again on the airbase’s jukeboxes.

The base had three clubs – the Officers Club, the NCO Club and the Airman’s Club – and just as among the military ranks, the bands sat in a hierarchy. The Filipino bands, which were the best, played for the officers. Huang’s group played for the airmen.

One of the three singers with Huang’s group was Julie Sue, or Su Rui, who, then just 17 years old, would in the ’80s go on to become one of Taiwan’s first rock stars.

One perk of playing in the house band was that Huang had a front-row seat to watch visiting US entertainers. The Platters, the Supremes, Gladys Knight, Brenda Lee, Roy Orbison, Lou Rawls, Gary Lewis & the Playboys and Bob Hope’s comedy troupe all came through Taiwan on tours of US bases in Asia, playing for raucous crowds of American GIs.

The band that left the biggest impression on Huang, however, was the Ventures, an instrumental quartet that was America’s quintessential surf-guitar outfit and responsible for the iconic theme song of Hawaii Five-O.

“We opened for them, and then we got to sit at the side of the stage and watch them play,” recalls Huang. “What really impressed me was that they had solos but no improvisation. Everything was perfectly in place.”

The Ventures’ instrumental guitar tunes were quickly and widely adopted throughout Taiwan. Traditional puppet theatre used the Ventures’ surf-rock tune “Pipeline” for chase scenes, mixing it into cassette soundtracks with other more traditional music.

“If you play this song for Taiwanese people, many won’t know it’s Western music,” says Hsieh. “They think it’s from a puppet show.”

Huang also remembers, “There was still segregation at that time. For the white soldiers, we played country music. Then when the black soldiers came in on Soul Night, we’d play soul. Playing for the black soldiers, I learned that to make the music swing, you don’t always play exactly on the beat. You have to vary it.”

Fast forward five years to 1974. Huang is 24 years old and stepping into a recording studio for the first time to cut a record with singer Chen Lan-li, a booming-voiced diva who dared to loosen up the beat to slide some hip-shaking rhythms, go-go beats and soul syncopation into records otherwise filled with lovesick Chinese ballads.

Taiwan’s recording industry was about to discover, as Huang now claims, “I was the only drummer who could play funk.”

When I ask Huang about recording Kao’s version of “Blue Monday”, he leans back in his seat and pauses for a moment in thought. “You know, last night I had to message a friend of mine – he’s a historian and knows these things – to ask if I’d even played on that album.

“To be honest, I couldn’t remember a thing about it. There were just too many recordings. But he told me, ‘Yes, you were on that album.’ So I guess I was.”

As the music plays, Huang begins tapping his hands on his knees in time with the beat.

“Yes, that’s me,” he says.

But when we get to Kao’s “Blue Monday” cover, he gives me a quizzical look.

About 30 seconds in, he declares, “There are no drums on this track. These are just drum machines.”

Huang then asks to see the record jacket. Scanning the credits, he identifies Danny Cheung, a Hong Kong keyboard player who is also credited with arranging all the songs on the album.

“Danny did it,” says Huang. “This whole song must be just Danny. The drum machines – everything. I can’t hear any instruments at all.”

Asked if he has any idea who might have selected the songs to record, Huang shakes his head.

“Cover songs were sometimes chosen by the singers and sometimes by the record companies,” he says. “But Kao was a big star, so he probably could choose the songs himself.

“Honestly, I was just the drummer. By the time they gave me the sheet music, those decisions had already been made.”

Han, Kao’s concert promoter, confirms that the singer chose much of his own repertoire. And Kao chose songs not only because he wanted to record them, but because he believed they’d make for exciting stage acts in nightclubs or on television.

As to how Kao first heard “Blue Monday”, or why he chose to record it, Han claims no direct knowledge. But if he was sure of one thing, it was this: “It had nothing whatsoever to do with New Order.”

“Nobody in Taiwan knew who New Order was,” says Han. “But they had a song on the Billboard charts. And because their song was on the Billboard charts, that’s why Frankie Kao played it.”