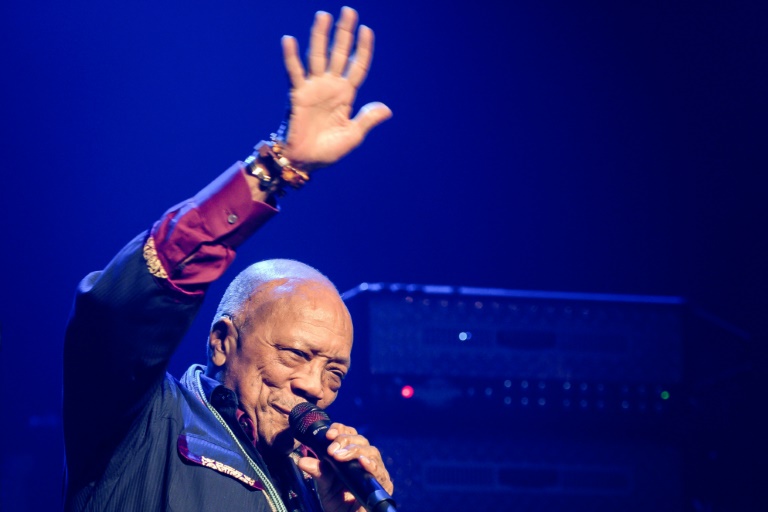

Quincy Jones, who has died at the age of 91, was a jazzman, composer and tastemaker whose studio chops and arranging prowess connected the dots between the 20th century’s constellation of stars.

From Frank Sinatra to Michael Jackson, jazz to hip-hop, Jones tracked the ever-fluctuating pulse of pop over his seven-decade-plus career — most often manipulating the beat himself.

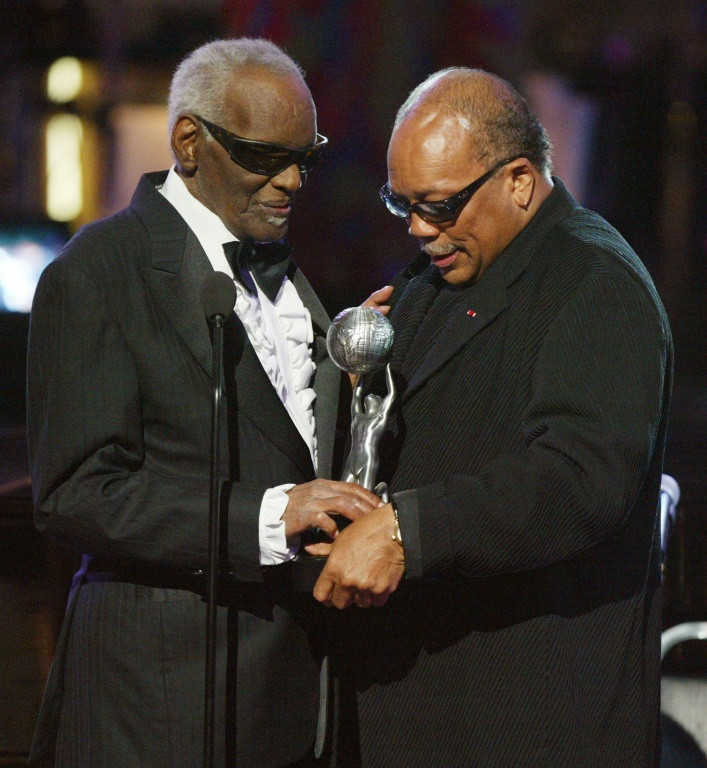

Gregarious and candid with a mischievous smirk, Jones’ life itself embodied the course of music history: he was teenage buddies with Ray Charles, musical director for Dizzy Gillespie, arranger for Ella Fitzgerald and the ringleader behind Miles Davis’ last major performance that became the live album “Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux”.

The child of Chicago’s south side produced everyone from Aretha Franklin to Celine Dion, and triggered a cultural earthquake in launching the solo career of one young Jackson — a musical marriage that produced “Thriller” and changed pop forever.

“You name it, Quincy’s done it. He’s been able to take this genius of his and translate it into any kind of sound that he chooses,” jazz pianist Herbie Hancock told PBS in 2001.

“He is fearless. If you want Quincy to do something, you tell him that he can’t do it. And of course he will — he’ll do it.”

Quincy Delight Jones Jr. was born March 14, 1933 in Chicago, to a mother who suffered from schizophrenia and was institutionalized when Jones was a young boy.

He and his brother Lloyd lived with their grandmother, a former slave, in Louisville, Kentucky, a period during which he has recalled eating pan-fried rats.

As a pre-teen, Jones returned to Chicago to live with their father, who did carpentry for the mob.

“I wanted to be a gangster until I was 11,” Jones said in the 2018 Netflix documentary on his illustrious career, directed by his daughter, actress Rashida Jones.

“You want to be what you see, and that’s all we ever saw.”

The elder Jones moved the two boys to Seattle, where Quincy discovered a knack for the piano at a recreation center — and history began.

“I’d found another mother,” he wrote in his 2001 autobiography.

Jones began playing local gigs, penning his first composition, developing skills in music arrangement and taking up the trumpet.

He met a teenage Charles after a performance by the soon-to-be blues and bebop pioneer, and the duo became mainstays in the local music scene.

Jones briefly studied at the Berklee College of Music in Massachusetts before joining bandleader Lionel Hampton on the road, eventually relocating to New York, where he gained attention as an arranger for stars including Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Count Basie and, of course, Charles.

The 1950s saw him head back on tour, in particular to Europe.

He played second trumpet on Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel”, teaming with Gillespie for several years before moving to Paris in 1957, where he studied under the legendary composer Nadia Boulanger.

He traversed Europe with a number of jazz orchestras — but began to realize that a name and talent did not always translate into money.

Finding himself in deep debt, Jones joined the business side of music, getting a job at Mercury Records where he eventually rose to the role of vice president.

“When it came to the people who actually own the label and who control the music, the Black people were not in control of that,” Hancock said. “We were like hired hands.”

“Quincy… opened the doorway.”

Jones expanded into Hollywood, scoring films and television shows.

He wrote his own hits, like the addictively cacophonous “Soul Bossa Nova”, while also arranging at a breathless pace for dozens of stars across the industry.

The musician began working with Sinatra, for whom he arranged the most famous version of the oft-covered “Fly Me To The Moon”, and forged a musical and personal relationship with the crooner that would continue until the singer’s death.

As much hypemaster as orchestral wunderkind, Jones had a nose for talent and launched star after star, crafting hit after hit.

While producing the soundtrack for the musical “The Wiz” starring Diana Ross and Jackson, Jones started the partnership that would birth “Thriller” — thought to be the industry’s best-selling album ever.

“You can’t explain something like that, you can’t aim at it,” Jones told Rolling Stone of the album’s smash success.

“It’s why I used to keep a sign in the studio saying, ‘Always leave space for God to walk into the room.'”

Among the entertainment world’s most popular celebrities, with enough stories to fill an encyclopedia and a resume that reads like a novel, Jones did not content himself with his countless musical stage and composing achievements.

Jones started a label, founded a hip-hop magazine, and produced the 1990s hit television show “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”, discovering Will Smith.

He introduced Oprah Winfrey to the masses, taking the Chicago talk show host to the silver screen by connecting her to Steven Spielberg, who cast her in his film “The Color Purple”. She scored an Oscar nomination for the role.

He backed Martin Luther King Jr and a number of humanitarian causes, particularly in Africa.

In a bid to raise money for the Ethiopian famine crisis in 1985, Jones gathered dozens of pop stars to sing the now classic “We Are the World”.

A regular on the glitterati’s party circuit who knew everybody who was anybody, Jones even said he was meant to have attended Sharon Tate’s dinner party where The Manson Family carried out its brutal murders — but apparently forgot.

“It’s just unbelievable, man,” he told GQ in 2018 of his fortunate slip. “Life is a trip.”

Jones’ roller-coaster personal life twisted and swerved nearly as often as his career. He had three wives, the actors Jeri Caldwell and Peggy Lipton, along with Ulla Andersson, a Swedish actor and former model. He fathered seven children, all girls but one, with five different women.

In 2018, when Jones was 84, he told GQ he was maintaining 22 girlfriends everywhere from Sao Paulo to Shanghai.

“When you’ve been a dog all your life, God gives you beautiful daughters and you have to suffer. I love ’em so much. They’re here all the time,” he told the magazine.

He suffered several health scares, including a near-fatal brain aneurysm in 1974, after which he stopped playing the trumpet for fear the pressure would unfasten the staples in his brain.

Jones said he suffered a “nervous breakdown” in 1986 from overworking himself, and in 2015 went into a diabetic coma and had a massive blood clot, prompting him to give up alcohol.

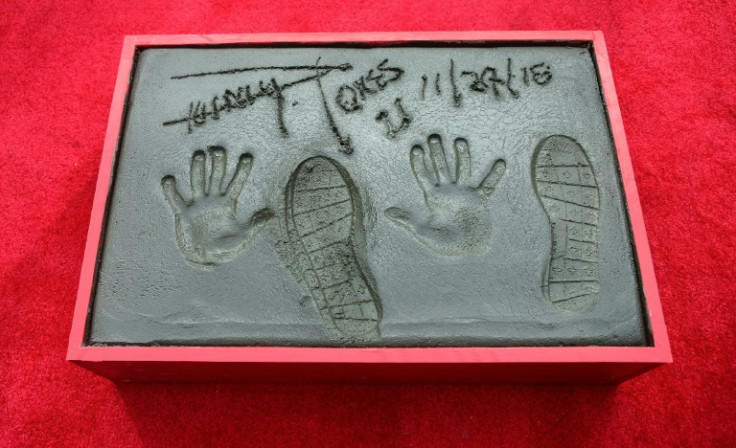

Among entertainment’s most decorated figures, Jones has virtually every major lifetime achievement award, including 28 Grammy Awards.

He’s also won an Emmy, a Tony, and an honorary Oscar.

In her documentary, his daughter Rashida asked Jones how he kept his ego in check while living such a remarkable life.

“You have to dream so big that you can’t get an ego, because you can’t fulfill all those dreams,” he told her.

“You only live 26,000 days,” Jones said — though in fact he lived thousands more than that.

“I’m going to wear them all out.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP