All over the world, a wander through local supermarket aisles offers fascinatingly unexpected insights into everyday consumer tastes. From locally produced seasonal foodstuffs to imported items sourced from across the globe, supermarkets allow glimpses into the broader cultures and societies they serve.

But like other universal aspects of life now taken for granted, well-stocked supermarkets – in Hong Kong and elsewhere – are relatively recent innovations.

These days, local supermarkets are among the single greatest social levellers found in any community. From society’s wealthiest members to the less affluent, virtually everyone now sources at least some of their daily needs from these establishments. But until recent decades, this was not the case.

The earliest prototype supermarkets began to appear in maritime Asia’s port cities just before World War I, and then burgeoned in the hectic decade of runaway global prosperity and technical innovation that characterised the Roaring Twenties.

As was usual during that period, American entrepreneurialism led the way. Across the region, long-established trading companies with pre-existing import-export divisions swiftly moved into expanded retail distribution of consumer goods.

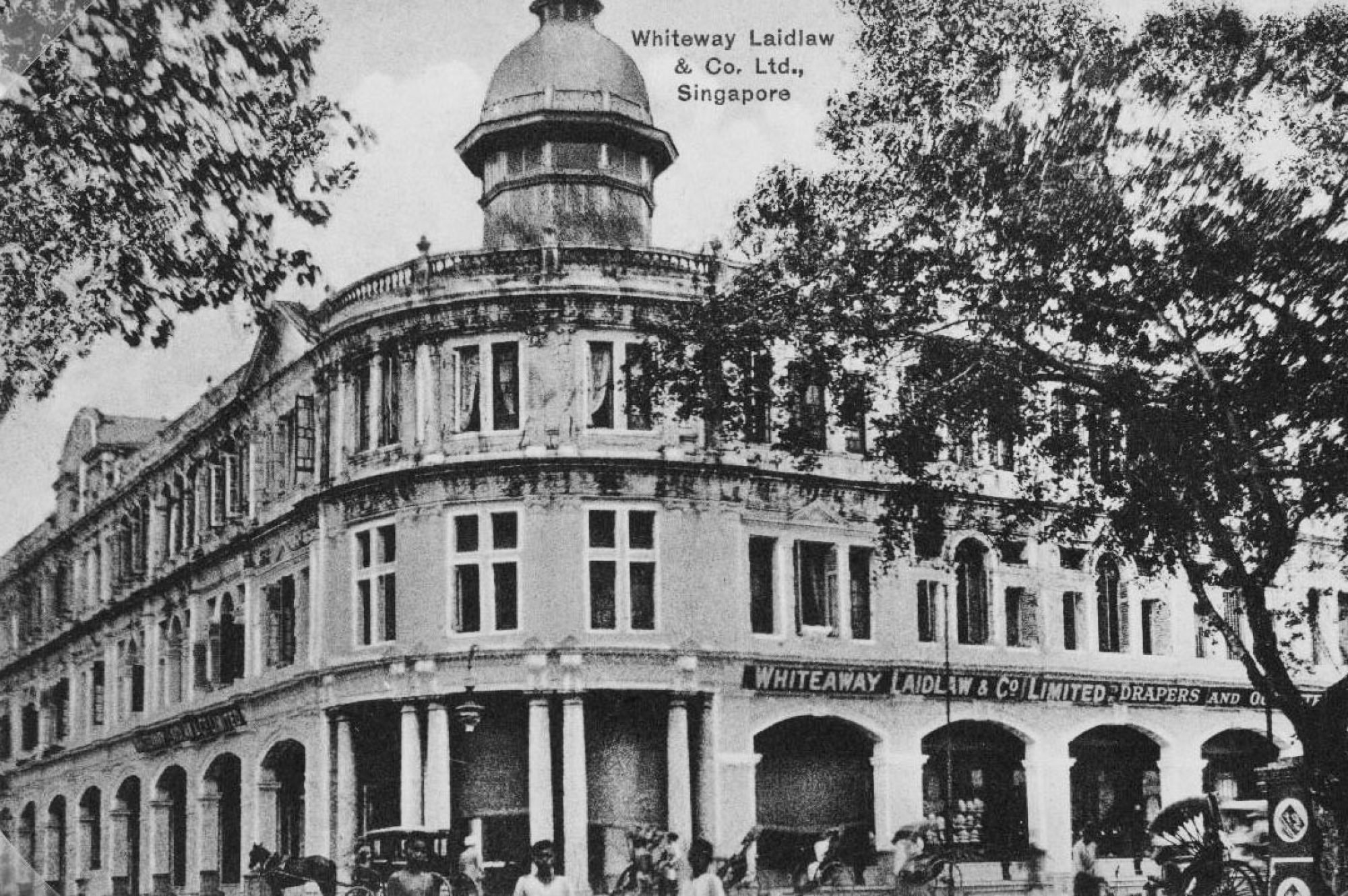

In the interwar years, Asia’s market leader was British firm Whiteaway Laidlaw, which had retail emporiums in every major port city from Calcutta to Shanghai, including Singapore and Hong Kong.

Amusingly punned as “Right Away and Paid For”, the firm astutely combined innovative elements of “cash and carry” grocery shopping, which was then rapidly coming into fashion in places such as Britain and Australia, with the cashless convenience of old-style Hong Kong comprador shop purchases.

In Hong Kong’s traditional comprador shops, which stocked everything from boxes of matches and tins of butter to imported meat and fresh fruit, individual accounts were kept in the shop’s ledger, purchases were signed for and a bill sent at the end of the month, which was then settled by personal cheque.

Some purchases may have been carried away on the spot, but most items were home-delivered.

Perhaps to the surprise of some today, comprador shop purchasing practicalities were not materially different to modern-day credit card shopping. Seasonal vouchers and early forms of “loyalty point programmes” were also on offer for regular patrons.

In pre-war Hong Kong, a prototype supermarket existed with Dairy Farm’s grocery shops. There were only three branches: in Central, on The Peak and in Kowloon Tong, and the small number accurately reflected the colony’s then-minuscule resident middle class.

The Dairy Farm shops stocked imported grocery items that European, Eurasian, local Portuguese or overseas Chinese customers from Western countries would habitually buy, such as bottled sauces and condiments, canned goods, refrigerated imported meat and cheese, and locally produced fresh milk.

Unsurprisingly, these branches were in residential catchment areas with significant target markets.

Along with the convenient purchase of everyday consumer goods, an element of real or imagined social class crept into these places.

Local proto-supermarkets were places where English was typically spoken – the shop assistants were often foreigners – and a general standard of dress, deportment and presumed savoir faire were expected from those who entered the premises.

Actual or perceived racism or general social snobbishness on the part of management, employees and other customers inevitably provoked a furiously indignant reaction from some who felt themselves – rightly or wrongly – to be unfairly discriminated against or excluded.

In the late 1960s, these establishments periodically became the focal point for small-scale anti-colonial protests by student groups and other social activists.

These were – in the Hong Kong way – rowdy but otherwise non-violent. Once their general point had been made, protesters soon dispersed.

With rising local affluence from the 1970s, along with changing consumer tastes, air-conditioned supermarkets became more widespread across Hong Kong and new branches opened up in districts where only small-scale grocery shops and wet markets had hitherto existed.