There was a time not too long ago when “Willem de Kooning and Italy,” at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, in Venice, would have had fans back in the U.S. gnashing their teeth. We are talking, after all, about the painter whose muscular slashes and jack-o’-lantern-faced women helped prove beyond any reasonable doubt that America, not Italy or France or England, was the new center of Western art after the Second World War. Centers come and go, though. European painting is still European painting. And so—much like how the macho, all-American Jackson Pollock is now unironically described as a neo-Mannerist, an arranger of curls and fussy El Greco serpentines—de Kooning has made the long voyage across the Atlantic.

The curators, Gary Garrels and Mario Codognato, haven’t exactly nailed the case for de Kooning’s Italian influences, not that they need to. Yes, he only made two extended trips to the country: once, for a few months in 1959, by which time his most famous images lay behind him; and again for a few weeks a decade later. (He watched the moon landing at a bar in Rome.) Yes, there are few works by other artists on view here, and just two by actual Italians. And yes, the catalogue is a treasury of hedges such as “And who knows whether de Kooning might have seen and discussed Mimmo Rotella’s torn posters.” All the same, de Kooning was a European-born, academically trained oil painter who loved Titian and spent hours scrutinizing Pompeii frescoes at the Met. He owed Italy a huge debt, and no amount of American jingoism can hush it up. Either way, the whole thing seems like an excuse to gather seventy-five de Koonings under one roof, and who could be mad about that?

But “Willem de Kooning and Italy” betrays a subtler shift in the artist’s reputation. For years, one of the louder knocks against him (voiced by Clement Greenberg, among others) was his old-fashioned pursuit of painterly eloquence. If this exhibition is any guide, the standard de Kooning praise is the same line, more or less, and it misses something. By the time of his death, in 1997, he was being celebrated for his sturdy, tasteful, well-balanced paintings: Accademia-worthy masterpieces, in short. One scans the catalogue in vain for mentions of the jolts and stutters of de Kooning’s compositions, or the crudeness of his faces and bodies—instead, his blends of beauty and glorious, wailing ugliness have been accepted as just another kind of beauty. Perhaps we’re unsure what other compliment we’re supposed to pay a great artist, but de Kooning, of all people, deserves a better one.

“How can a great work of art be something other than a masterpiece?” was among the toughest problems of mid-century American aesthetics. You can find Mary McCarthy gnawing on it in reviews of “Pale Fire” and “Naked Lunch,” novels that don’t “work out” or enlighten or do any other normal masterpiece things but simply go on turning, like perpetual-motion machines. The film critic Manny Farber prescribed rambling, unpretentious “termite art” as the cure for “white-elephant art” that was burdened with the “gemlike inertia of an old, densely wrought European masterpiece.” Harold Rosenberg had de Kooning, a friend of his, in mind when he wrote about “Action painting”—art where the goal wasn’t the stylistic perfection of the image but the expression of vigorous, semi-mystical selfhood. Radical, non-masterpiece ways of thinking about art were everywhere in postwar America. Few stuck.

There is one rather obvious reason why: many of them are insanely complicated. Trust nobody who claims to understand every word of Rosenberg’s “The American Action Painters.” And yet, even if you grasp less than half, you can see what Rosenberg was getting at when you walk through this exhibition. If abstract art was about the self, then it was about contradiction, tension—all problem, no resolution. During de Kooning’s first visit to Rome, in 1959, he began a series of oil-on-paper compositions in black-and-white. These are not especially large images, but they’re encyclopedic in their variety of marks and textures. The clever squirrel tail of shiny ink in the upper left of “Black and White Composition” (1960) does its little wiggle and is replaced by a splatter and then a large, thin smear. Nothing comes together or follows from anything else. Instead of progress, a twitch.

De Kooning was in his mid-fifties when he made this picture, and in a sense he was still starting out. He had come to New York from the Netherlands in his twenties but didn’t have his first one-man show until he turned forty-three. For years, he was among the highest-profile abstract painters in America, though “Woman I” (1950-52), his return to figuration, made him a traitor to both sides. I get the feeling that he loved this. You could interpret the art in “Willem de Kooning and Italy,” in fact, as a single, frantic, four-decade refusal to get comfortable making any kind of art, or to allow anybody to get comfortable looking at it. As a young student in Rotterdam, de Kooning developed a fluid, eloquent line, and you can find it even in an abstraction as wild as “Door to the River,” which was completed shortly after he’d returned from his first Italian trip. Thick, wide yellow brushstrokes bounce off the upper limit of the frame like a patient in a rubber room—it’s hard to believe it’s the same yellow that, in the center, dribbles into a block of dozy, babyish pink. There is no making peace with this painting. Standing before it, however, you may wonder whether peace is overrated.

If your goal is to stay uncomfortable with art-making, it’s not enough to use clashing techniques. You need to take on new media, and that, as much as anything else, may have been what Italy represented to de Kooning. In 1969, on visit No. 2, he ran into an old friend, the sculptor Herzl Emanuel, and began, in his mid-sixties, a career in bronzes. The earliest specimens displayed at the Accademia are no better than you would expect from a first-timer: squashed little bodies with flailing cartoon limbs. (“I made them very fast,” de Kooning said, as though we couldn’t tell.) Over the next few years, he taught himself to combine sculptural savvy and innocence into something more powerful than either. The result is “Clamdigger” (1972), which keeps the squashy, gnarled texture of de Kooning’s initial dabbles but adds a sense of weight. Everything in this figure tugs downward: slumped shoulders, clown-shoe feet, a thin-thick left arm that looks ready to snap off. The thing to notice is the tool in his right hand, something between a spade and a club. Without it, he’d be more metaphor than man. Armed, he’s a guy with a job, matter-of-factly himself, a Giacometti figure you could watch the game with.

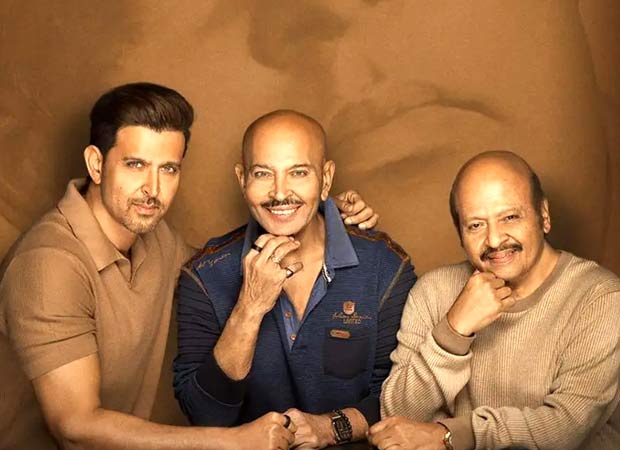

“Clamdigger,” (1972).Photograph courtesy The Willem de Kooning Foundation / ARS

“Clamdigger” reminded me of what’s ingeniously absent from most of de Kooning: gravity. The exhibition’s wall text notes that he sketched Crucifixions but never painted one, and it’s easy to push the point further. A Crucifixion is a genre of European art in which gravity kills Christ, allowing his spirit to rise up to Heaven. In various paintings and sculptures, de Kooning does anti-Crucifixions: figures neither quite alive nor dead, refusing to float or sink or play a part in any story. “Hostess,” the grinning, waving bronze that kicks off this exhibition, looks like a Crucifixion, if being crucified were the comfiest thing in the world. And notice how “Woman, Sag Harbor” (1964), pushes up and down at the same time—the red, flaming arabesques in the lower half of the canvas cancel out the meaty orbs above. The painting’s blond pinup model is also a green-tinged corpse, easy to fear or worship but impossible to entirely understand.

Calling this painting a masterpiece would be like putting a leash on a wolf, though by now de Kooning’s domestication is probably a foregone conclusion. It’s the way of all canons: Action painters and termite artists join or are forced into tradition while their audiences numb to everything that was once weird about the work. There’s some justice to this, but de Kooning had higher hopes, and not just for his own art. “I do feel rather horrified,” he said in a 1949 lecture, “when I hear people talk about Renaissance painting as if it were some kind of buck-eye painting good only for kitchen calendars.” For the rest of the lecture, he made a case for the Renaissance as the golden age of wild, vulgar image-making—almost demonic in its conjuring of flesh where it shouldn’t be. “The more painting developed,” he said, “the more it started shaking with excitement . . . the artist was too perplexed to be sure of himself.” That was centuries ago. Excitement and perplexity have long since stiffened into certainty. But the real accomplishment of “Willem De Kooning and Italy” might be to give the canon some of its tremble back: to make Accademia visitors go upstairs, find Bellini’s Madonnas, and imagine a time when they looked at least as wild as “Woman, Sag Harbor.” ♦