‘Let’s see what the adjectives are,” says Jason Allen-Paisant – as if to make it even more obvious that he is a poet – when I ask how he’s feeling the morning after winning the TS Eliot prize for poetry. “Great. Overwhelmed. Ecstatic. Privileged.”

Although you wouldn’t know it from his warmth and attentiveness, he is also very tired. The 43-year-old writer and academic couldn’t sleep properly after the ceremony, and ended up taking a walk through London in the early hours of the morning. “It’s not that I wasn’t expecting to win,” he explains. He knows his victorious work, Self-Portrait as Othello, is a “strong book” – it had already won the Forward prize for best collection, and is on the shortlist for the Writers’ prize (previously known as the Rathbones Folio prize). But “it’s mad”, he says, to be named the winner from a shortlist that included “at least two” poets whose work Allen-Paisant has taught to his students at Manchester university, where he is a senior lecturer in critical theory and creative writing.

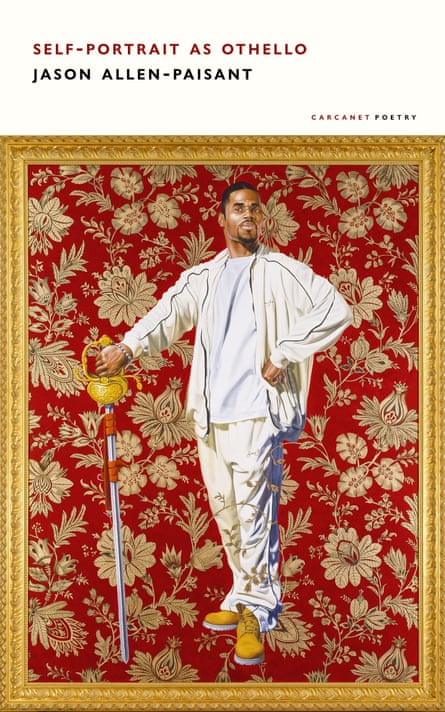

Described by its publisher Carcanet as a “poetic memoir and ekphrastic experiment”, Self-Portrait as Othello imagines the backstory of Shakespeare’s character, exploring his experiences of immigration and Blackness via the poet’s own life. Allen-Paisant thinks one of the reasons it resonated with readers and prize judges is because “it balances several interesting questions”, exploring “masculinity, Black masculinity, and how that intersects with vulnerability. Which is not a conversation that’s had enough.”

Othello is also “in”, he informs me, citing productions last year at the Lyric Hammersmith and Riverside Studios in London. He, just like these productions, wanted to ask questions about the character that are not addressed in the play. (One poem in Self-Portrait as Othello is titled “What Shakespeare did not write about”.)

“It’s too easy to think that he just becomes demented,” says Allen-Paisant. “Is there some cultural baggage he’s carrying? Is there something in his background?” The poet also wanted to explore the identities that he and Othello share as men of colour, as immigrants. Allen-Paisant grew up in Manchester in Jamaica, born to a mother who was studying to be a teacher and a father who left before he was born. He lived with his grandparents, yam farmers, during his early years, in a small village called Coffee Grove which he describes in the collection as being “where hope is like the dry root of a red dirt rockstone”.

“For a lot of my life, all I was trying to do is turn my back on that place,” he says. “You know, upward mobility: get your education, go to university.” He didn’t want to talk about his family or hometown when he was younger, because farming wasn’t “cool” and coming from a poor background “was a source of shame”.

He left Coffee Grove at the age of five to live with his mother in Porus, where she was living having qualified as a teacher. This was when he remembers realising that his grandmother, who appears as “Mama” in his poems, wasn’t actually his mother. “It was actually a real trauma,” he says. His grandmother dropped him off at his mother’s house in what he believed to be just a visit. Then, while he was in he toilet, she left without saying goodbye.

Although she didn’t get much education herself, his grandmother made sure her daughter and grandson did. She was the one who taught Allen-Paisant to read “on her veranda with the blackboard”. She told him: “You gotta read your books! Take them books seriously.” Which, of course, he did, completing a degree at University of the West Indies in Kingston, then travelling to Montreal for the first year of his PhD in medieval and modern languages, before gaining a scholarship to complete his doctorate at Oxford, with a year abroad at the École normale supérieure in Paris. He had been writing poetry since he was an undergraduate, but at Oxford “something shifted and I started doing it seriously”.

after newsletter promotion

Possibly because of their parallels, his mind led him to Othello, and how the character could be seen differently through a Black lens. Through writing about Black masculinity, he inevitably found himself thinking about his own father – or his absence, a key theme in Self-Portrait as Othello. Allen-Paisant’s father was a traveller, the poet knows from speaking to his paternal grandmother. He lived in England and the US, and is now in Ethiopia. In an aptly poetic turn of events, Allen-Paisant is flying there after our interview, to meet his dad for the first time.

Now a father himself, the poet wants to be able to tell his two children about their lineage. “I don’t need anything from him materially, obviously,” he says. “I don’t need anything from him emotionally, either. I think I just want to hear him out.” He is surprisingly calm as he tells me about this planned trip – a trip he hasn’t yet told his father about.

But perhaps it is not so surprising that a poet who takes on such thorny subjects in his work would also be willing to take part in difficult real-life conversations too. “I love talking about awkward things,” he says. “I love talking about things that nobody wants to talk about.”

In his TS Eliot acceptance speech, he expressed his horror at the war in Gaza, saying he wanted to “bring it into the room”. By winning the award, he says, he was given a platform. “I wanted to use it to talk about something that I think matters to my fellow poets.” He cites the late Benjamin Zephaniah as an inspiration – particularly when he turned down an OBE. “There comes a point where you have to look at yourself in the mirror, is what he was saying. I was really taken by that. I found it courageous. And I think that’s the ethic that probably led me to say what I said yesterday.”

For now, Allen-Paisant is leaving poetry to one side while he works on a memoir-cum-nature book, due in 2025. He has also been writing fiction “in secret”, which he may try to publish at some point. “But I’m not trying to kill myself or give myself burnout,” he says calmly.

In fact, calmness almost seems to emanate from the poet, perhaps because, after years of trying to distance himself from his origins, he has finally come to terms with his roots. “I know myself now,” he says, and can laugh at the fact that “Paisant”, the name he has taken from his Breton wife, means “peasant”, a pleasing shoutout to his own family’s past. “It does feel like coming full circle,” he says.