When it comes to the perception of the threat posed by Iran’s nuclear-weapons program, everything changed on April 13.

Until the massive attack of around 350 aerial threats – of which there were about 120 full-fledged ballistic missiles – observers worried about Iran’s messianic designs and style, but they also counted on a risk-averse leadership.

After April 13, no one knew what Iran might dare to try – consequences be damned.

Before April 13, observers knew that the Islamic Republic promoted low-grade terrorism in wild and unpredictable ways, but they also knew Tehran avoided large-scale conflicts – carefully.

This definitely meant that no matter how badly Iran wanted a nuclear weapon, it would remain deterred from crossing certain redlines out of fear of a large attack.

The US or Israel could carry out major operations against Iranian officials or facilities, both in Tehran itself and around the region, but the ayatollahs would not strike back too hard for fear that in a real escalation, they would be crushed.

No matter how far Iran progressed in nuclear enrichment – to 60% since 2021 – and no matter how badly it was violating its inspection obligations to the International Atomic Energy Agency, which has been blindsided since 2021, the assumption was it would never move forward with its weapons group.

Without progress in its weapons group – involving miniaturizing a nuclear warhead to be delivered on a ballistic missile, as well as special detonation issues – the Islamic Republic would not be able to deliver a nuclear weapon against a foe, even if it theoretically could produce an atomic bomb.

Observers began worrying in February, when former Iranian nuclear chief Ali Akbar Saleh said the regime had “all components” necessary for building a bomb.

Building a bomb “not complicated”

Iranian nuclear scientist Mahmoud Reza Aghamiri, who is close to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said on state television on April 7 that Khamenei “can change his stance tomorrow” on building nuclear weapons, and that his regime “has the capability” to make the leap because building the bomb is “not complicated.”

There have been a number of other recent and increasingly aggressive statements by Iranian officials, suggesting that they could almost immediately carry out a nuclear test, and all that is needed is Khamenei’s approval.

These statements raised eyebrows, but overall, most Israeli defense and intelligence officials still viewed Tehran as six months to two years away from a nuclear weapon due to the remaining weapons group issues to address.

There were also some increased concerns after October 7.

Some worried that if Hamas had perceived Israel as so weak that it was willing to invade, maybe the much stronger (than Hamas) Iran would perceive Jerusalem as too weak to carry out an attack against the Islamic Republic’s nuclear facilities should it try to leap across the finish line.

Another radicalizing factor could be Iran’s new heavily improved alliance with Russia and China, Mossad Iran analysis desk chief and INSS expert Sima Shine wrote on Tuesday, as the ayatollahs are helping Moscow keep its war with Ukraine going, despite Russia running out of missiles and drones.

Khamenei has been supplying weapons for Russia to keep up its intense attacks as far back as October 2022.

It is not even clear at this point that anything Israel or the US might do will succeed in bringing Iran back to a modification of the original 2015 nuclear deal.

In 2015, the ayatollahs were viewed heavily as outcasts worldwide, and even Russia and China cut them off from trade.

But in mid-2024, Moscow and Beijing proved to be Khamenei’s most stalwart allies.

If that is true, then it is hard, in the current setup, to see Iran being ready to make the necessary compromises to return to a nuclear deal in the near future.

And if the Islamic Republic has not been ready to make compromises since 2021, isn’t it just a matter of waiting for the right moment to break out a nuclear weapon when the US, Israel, and the world will be a bit more distracted?

April 13 raised eyebrows, concerns about Iran’s link to Russia and China, and also other problems in perceiving Iran’s nuclear threat as the most imminent since it was created three decades ago.

If Iran’s ballistic missiles had killed hundreds or thousands of Israelis – which they certainly could have done if even only a few hit populated areas – the Jewish state would have responded with unrestrained ferocity.

That means that when Iran ordered the massive strike, it not only did not care about Israeli civilians, it was ready for the possibility of a larger regional war.

Multiple current top Israeli defense officials, along with Shine, without referring to specifics, have said Iran is actually progressing on aspects of its weapons group that it had not worked on in the past.

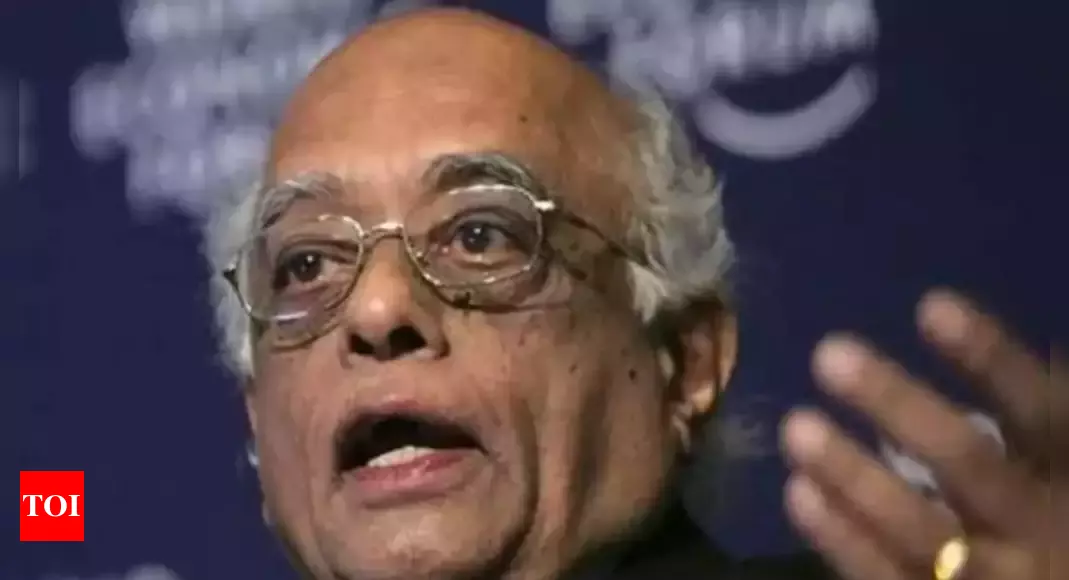

If Tehran is closer than ever to the bomb, then why did IAEA Director-General Rafael Grossi run to Iran last week to try to restart negotiations for a nuclear deal?

What is the point, when Grossi has said his team has “lost continuity” in terms of knowing where Iran’s nuclear program really stands – after being cut off from many aspects of the program since 2021?

It could just be Grossi being endlessly optimistic to try to save negotiations as long as Iran has not crossed the nuclear threshold.

It could be an attempt by the Islamic Republic to confuse Israel and the West as it tries to sneak out with a nuclear weapon.

It could also be that all the sides are looking at US presidential polling and realizing there is about a 50% chance of Donald Trump returning to the presidency in January 2025.

Would he return to his “maximum sanctions” campaign against Iran? Might he succeed at decoupling Moscow from Tehran in part of a grand transactional trade-off in which Trump gives Russian President Vladimir Putin what he wants on Ukraine in exchange for what America wants on Iran?

The Biden administration would never trade Ukraine’s fate to go after Khamenei, but Trump, who has opposed assisting Ukraine, might flip the board on these issues.

So, all of the current parties could be ready to finally rush to a new deal to try to preempt new cracking down from a potential new Trump administration.

Or again, negotiations could be a distraction against a newly aggressive Islamic Republic that wants to go nuclear.

April 13 made the whole world view Iran through a much more dangerous lens. How and if this increased danger will lead the world to unified action that could finally make a difference is anyone’s guess.