This exquisite Mahayana Buddhist temple near the central Javanese city of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, is the biggest in the world, and dates to the eighth and ninth centuries. In its aesthetic, architecture, wisdom and history it is as superlatively astounding as those in Cambodia’s Angkor Wat temple complex.

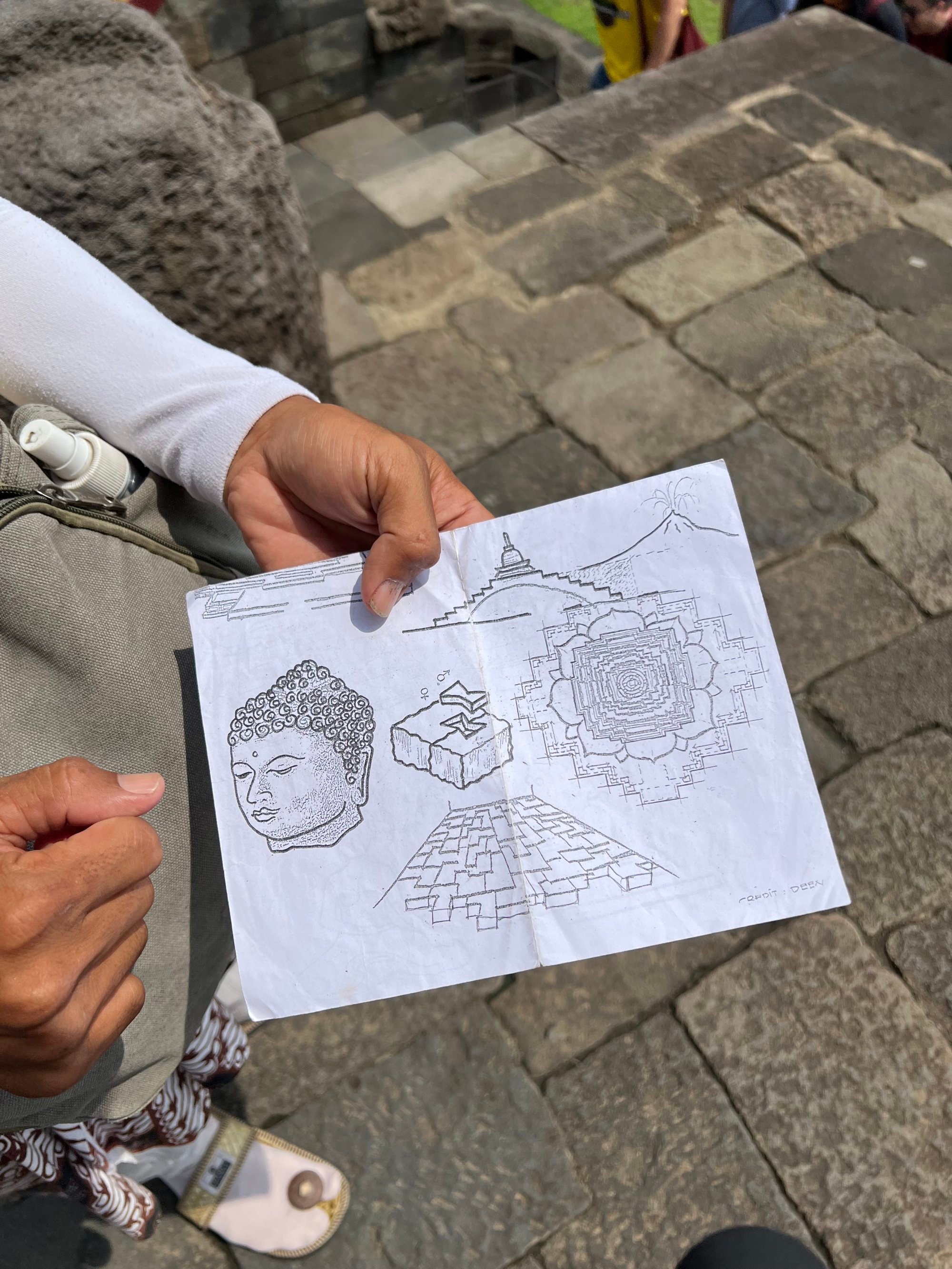

The three-tiered hilltop structure takes the shape of a mandala from above and its upper stupa can be seen poking up from the horizon from the circumference of hilly countryside around it.

From a pyramidal base rise four graduating galleries with 2,670 stone bas reliefs depicting a unique tableaux of society as it was 1,200 years ago. The people are drinking, gambling, cooking and hunting; grandparents are tending gardens; children are playing. It’s like an ancient Instagram feed.

Where to travel in 2024, according to the experts – and where to avoid

Where to travel in 2024, according to the experts – and where to avoid

From these galleries, the path ascends to three circular platforms where an astounding 72 stupas are crowned in heavy dovetailed black stone latticework. Within each of these stupas is a seated Buddha, only 16 of which have not had their heads stolen. The top of the temple – the “nirvana” or “supreme wisdom” – is graced with a monumental stupa rumoured to have once been covered in gold.

Unesco added Candi Borobudur to its World Heritage list in 1991, and the temple has seen a number of restorations in its time, but it is still as mythical, mystical and magical as it is unknowable.

From its foundation layer of 160 erotic panels hidden behind a belatedly reinforced wall, to its 300 stolen Buddha heads, 135 of which are still secreted away in private collections in Europe, anthropologists contend that we only know about 50 per cent of the stories Candi Borobudur could tell.

All this considered, it’s surprising to hear that the temple’s recent history is at odds with the sanctity of the place.

As we’re walking toward the temple, past manicured lawn, orderly queues and diligent-looking security, my guide, Din, tells me how happy he is with the changes to Candi Borobudur since it reopened in March this year.

Sensing a willing ear, he goes on to say that in March 2020, coinciding with the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, local authorities were pressured by Unesco to close the temple due to ongoing problems, including vandalism, graffiti and chewing gum.

“There were candy wrappers inserted between the gaps in the carvings; even ends of cigars butted out on the stone, and lots of graffiti,” Din says, shaking his head, apparently still not quite believing the behaviour.

Din grew up in the neighbourhood around Borobudur.

“As a child I was running around the temple with my friends and climbing on the stupas,” he says. “One of our favourite things to do was find coins that were thrown into the stupas by Chinese tourists for good luck.”

But having worked at the temple since 2008 he now counts himself as one of its chief protectors.

“Before the closure, kids would climb on the stupas and poke their umbrellas into the panels. And there was no toilet, so they’d urinate in water bottles, which would get tipped over,” he says.

“It was from foreigners and locals. Everyone. People didn’t care. Some visitors just don’t understand why these rules and regulations are important.”

The situation sunk to a new low in 2016, when a certain energy drink manufacturer filmed an unauthorised advertisement at the temple featuring an athlete doing parkour-style acrobatics over the stupas.

Another stunt saw an – again unauthorised – photographer breaking the top off the stupa that he was holding as he leaned out to take a photo. According to Din, he sprinted into the jungle never to be seen again.

The local practice of climbing on the stupas to touch Buddha for good luck was also an issue, with the stone gradually wearing away. That practice was stopped in 2019 after a baby’s head got stuck in stone lattice work and a stupa had to be crowbarred open.

New rules and regulations aim to conserve the temple and “preserve historic and cultural wealth”, according to the government.

The temple complex is limited to 1,200 visitors a day: 150 per hour, across eight hourly time slots. The entry tariff has risen from a flat rate of US$25 to US$90 (around 1.4 million rupiah) for foreign tourists and about US$50 for domestic tourists.

Visitors are given bamboo, flip-flop-style slippers to wear and must be escorted by guides who are employed from the local community.

To stop stunts like those mentioned above, ID must be shown when purchasing a ticket and individual visitor information is stored in wrist bands, which are scanned by security to ensure time limits are respected.

“There’s no food allowed now … especially no peanuts, so people can’t throw the wrappers,” Din says. “That was another issue.”

As I roam around the stupas, I see the occasional lump of chewing gum tacked onto a 1,200-year-old stone carved panel. But, with school kids only allowed into the grounds and not onto the temple proper, I’m relieved to hear there are fewer issues with urine, umbrella-poking and liquid paper.

“You know, they used to like to write things like ‘Dea loves Hari’,” Din says, scanning the crowd as if to catch someone planning to scrawl a declaration.

While Din approves of the new regulations, others lament simpler times. Patrick Vanhoebrouk, an anthropologist who lectures to guests at the nearby luxury Amanjiwo hotel on Java’s temple history, reminisces about a time “when I would spend entire days roaming around the temple, examining the panels”.

Now he is limited to one hour at a time, but concedes his anthropological work and research into the temple’s ancient tantric learnings sometimes enables him to have access to the temple after hours.

Once, a lucky few people took private tours to the top of the stupa to see the golden light kiss the land at sunrise. Now the temple is open only from 8am to 4pm, and the top stupa is no longer accessible to the general public.

“The problem with opening for sunrise,” Din says, “is that too many elderly people were losing their footing in the dark, falling over and injuring themselves.”

When our hour on the temple is at an end and we are making our way down, I note the steps are steep and the ledges a little untrustworthy. Sure footing and decent light do make sense.

I visited Borobudur a decade ago and remember roaming around freely, with few tourists and no security. But my visit in November, dutifully wearing my wrist band and bamboo slippers, and following my guide around, was just as magical – and just as imbued with rich history and the ancient unknown.