Shaw and Chor’s decision to make the film in Cantonese, rather than in Mandarin, played a big part in its success.

As Hong Kong has always been proud to be a Cantonese-speaking city, the dominance of Mandarin-language films during the 1960s and early 1970s can seem confusing.

Cantonese-language films were dominant until the 1960s – social dramas and martial arts movies aimed at a working-class audience. But in that decade, Shaw’s Mandarin-language films, mainly huangmei diao (regional opera) musicals and wenyi (literature and art) romances, became popular.

Shaw distributed its films across Asia to cater to the Chinese diaspora, and back then that was a largely Mandarin-speaking demographic, so Mandarin-language films served the company’s wider interests.

Shaw’s Mandarin films had much higher production values than their Cantonese-language counterparts and their more sophisticated stories appealed to the new middle class that was forming in Hong Kong.

The overwhelming success of Shaw’s classic and thoroughly modern martial arts films – along with the rise of Cantonese-language television – in the late 1960s led to the total collapse of the Cantonese-language film industry in 1971, even though Mandarin films presented a language barrier for many.

But the success of The House of 72 Tenants swung the dial back to Cantonese-language cinema in 1973, and Mandarin films slowly died out during the rest of the decade.

This happened more by chance than by design; The House of 72 Tenants has often been described as a “box-office miracle”. It was actually a run-of-the-mill assignment for Chor, which he dashed off without much fanfare.

A Cantonese version of the Shanghainese play was popular in Hong Kong at the time, and that inspired the production, although Chor wrote the film’s dialogue himself.

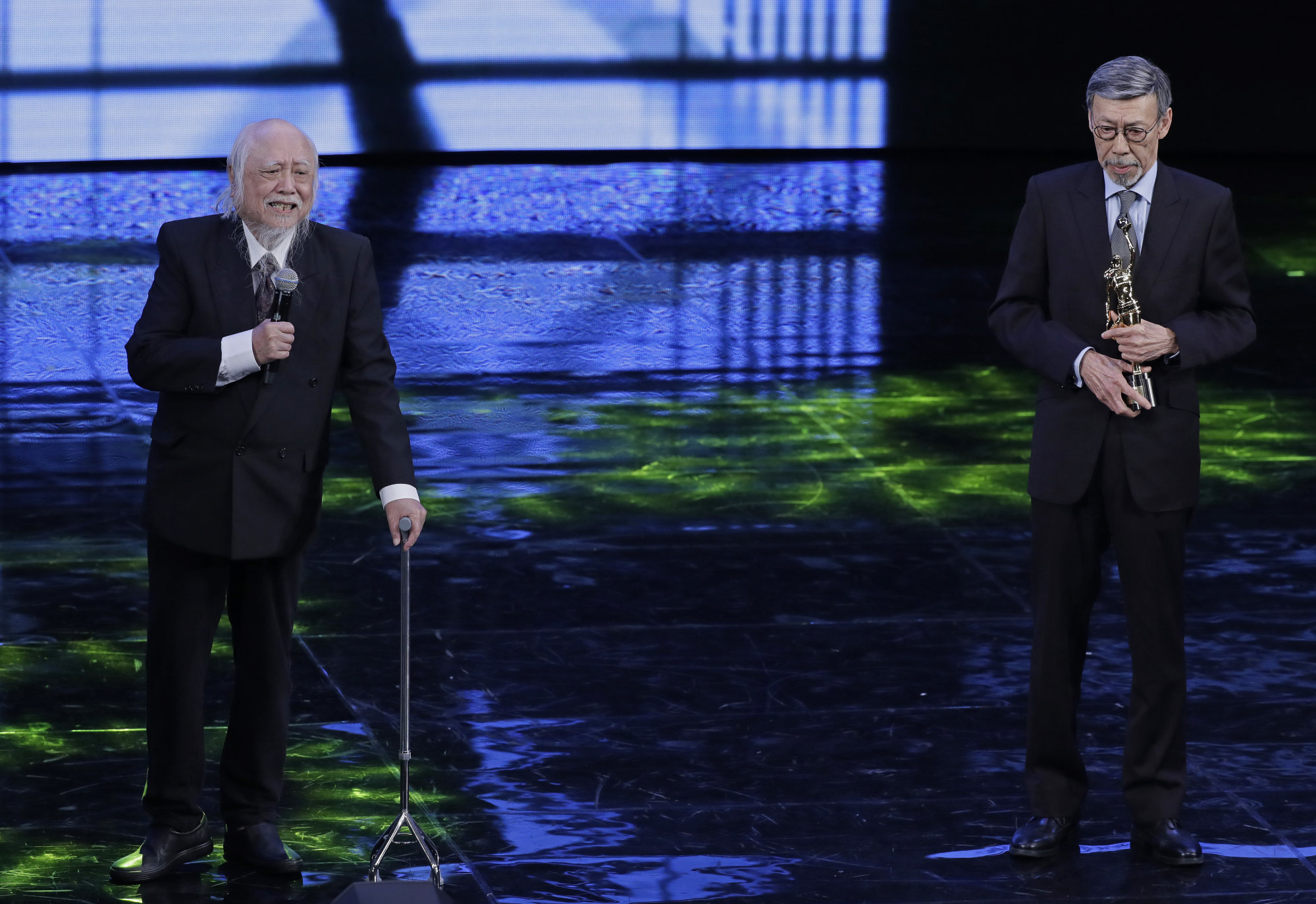

“The success of The House of 72 Tenants had much to do with the success of the stage play. I had little to do with it being well received,” Chor modestly told the Film Archive. “My main contribution was to make it more localised. I was much influenced by Italian Neorealism when I was growing up, so I put in elements of local culture.”

Chor essentially filmed a stage play; consequently, the camera is relatively static and the story is told through dialogue rather than images. But it is this dialogue that made the film such a big hit, especially as Chor picked up on the local street slang of the time.

“The adoption of lively colloquial Cantonese dialogue made Hong Kong people feel in touch with their own mother tongue again, and paved the way for the renaissance of Cantonese culture,” one critic wrote.

The story is set in mainland China’s Guangdong province sometime in the past. It is an ensemble piece that revolves round a group of tenants fighting with their malicious landlady and her scheming husband, as well as a corrupt policeman on the take. (The original Shanghainese play focused on the policeman and his attempts to rip off the tenants.)

There are many small events, such as the theft of an expensive piece of material from a tailor, but the main story develops when the tenants band together to stop the landlord’s young maid being sold off as a bride.

“Audiences will immediately warm to the undaunted spirit of cooperation and generosity, albeit portrayed overly idealistically,” the Ming Pao newspaper review said in 1973.

The Post’s critic noted the humour: “From the frequent laughter around the theatre there seemed to be a good many jokes. 72 Tenants is bawdy, bold, topical, generally anti-establishment and, to some extent, true to life,” he wrote.

Others reviewers thought that Hongkongers could see many of their contemporary problems reflected in the troubles of the characters.

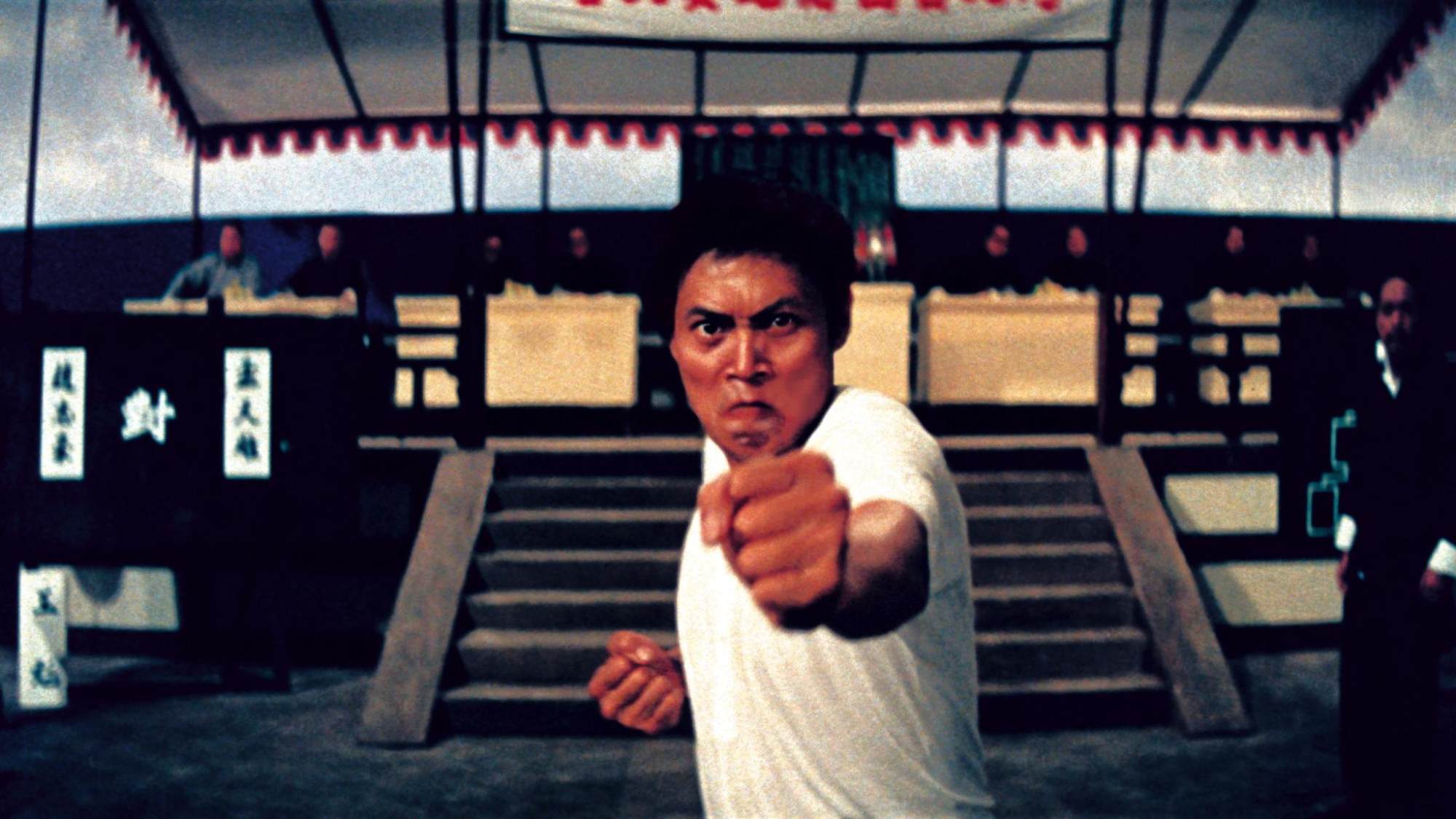

The casting was another reason for the film’s success.

“I used entertainers from the popular television show Enjoy Yourself Tonight [EYT], despite their lack of experience in films, simply because the audience liked them. My cast comprised one-half EYT artistes and one-half Shaw actors,” Chor said.

After working with the EYT stars, Chor became obsessed with adapting popular television dramas for the big screen, even though his boss Shaw said that this was a mistake, as such adaptations always failed at the box office.

The House of 72 Tenants had been adapted for the screen as a Cantonese comedy once before, for the 1963 mainland Chinese production of the same name.

“In our version, the theme centred on eviction and the struggle against it,” its director Wang Weiyi said.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.