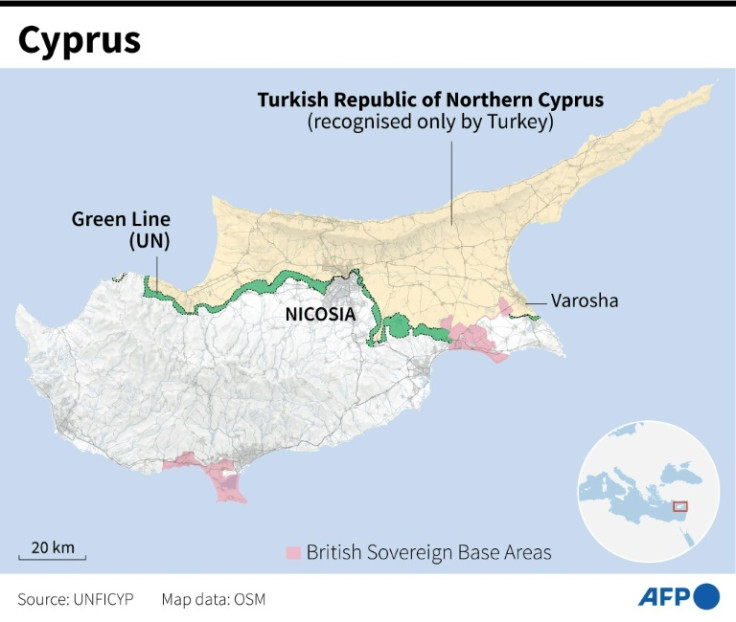

Cyprus marks a half-century of division this month, with the unresolved conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots branded on the landscape in a UN-patrolled buffer zone that cuts across the island.

Ghost villages, watchtowers and streets blocked off by concrete-filled oil drums offer a daily reminder of the brief but seismic events of 1974 that split the country in two.

As Cypriots contemplate the five decades since their communities were torn apart, many see little reason for optimism after witnessing round after round of abortive reunification talks, the most recent in 2017.

Demetris Toumazis had been due to finish his military service in the Greek Cypriot National Guard on July 20, 1974. Instead, he found himself fighting an invading Turkish army.

Taken to Turkey as a prisoner, he returned three months later to a divided homeland.

“Nobody expected things to turn out the way they did, and it’s 50 years now and there’s still no solution, and there’s no hope,” Toumazis said.

George Fialas, a fellow Greek Cypriot veteran of the conflict, told AFP that reunification was “a lost cause”.

“I don’t believe that we will be back (reunified),” he said.

Fialas too was performing his military service that summer. Like Toumazis, he was posted close to his family home in Varosha, a suburb of the costal city of Famagusta that was then the island’s premier beach resort.

He described chaotic scenes during the invasion with little information available, deadly air strikes and no news of his family just a few kilometres away.

“I didn’t know where they went, and they didn’t know where I was… there was no communication,” Fialas said. It would be months before he saw them again.

The invasion was the culmination of a fractious period in the island’s history.

A British colony since 1878, Cyprus became independent in 1960, but only after a bloody four-year insurgency by Greek Cypriots seeking union with Greece.

Instead, Britain, Greece, Turkey and Cypriot leaders negotiated for the island to become independent under a delicately balanced constitution.

This guaranteed representation for the Turkish Cypriots, who then made up around 18 percent of the population, and forbade both union with Greece or Turkey and partition.

That system collapsed in intercommunal violence in late 1963 that prompted Turkish Cypriots to retreat into enclaves before international peacekeepers deployed.

An uneasy status quo lasted a decade, before the military junta in Athens instigated a coup on July 15, 1974 seeking to unite the island with Greece.

Turkey responded by landing troops on the island’s north coast.

It was during the invasion that Toumazis and his mortar unit were captured outside Nicosia when Turkish tanks burst through National Guard lines and surrounded them.

“The whole line was broken,” he said. “We were behind factories — we had no idea what was happening and so we were stuck there.”

He was eventually taken to Turkey, only returning to Cyprus in October, by which time most of his family had fled abroad.

In 1983, the north unilaterally declared independence as the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus, a state recognised only by Ankara, which keeps thousands of troops on the island.

The United Nations, whose peacekeepers patrol the buffer zone between the two parts of the island, is making a push for new talks, but Stefan Talmon, an expert on Cyprus at the University of Bonn, doubts there will be any breakthrough.

“Any solution would mean that each side has to compromise and has to give up its sole decision-making power for its community. And I don’t think that either side is interested,” he said.

A new UN envoy was appointed this year hoping to rekindle talks, but decades of failure have left little grounds for optimism.

“We have now had at least two or three generations that… never knew a united Cyprus,” Talmon said.

Huseyin Silman, a 40-year-old from Nicosia who works at the Turkish Cypriot Global Policies Center think tank, said the younger generation, who grew up after the opening of crossing points between north and south in 2003, gave him hope for the future.

“When I was in school, the history books were quite one-sided. They were teaching us that it was all the Greek Cypriots’ fault, that Turkey came and saved us, and Greek Cypriots were our enemies and they killed us,” he said.

Younger Cypriots, however, had grown up in an era when crossing between the two sides is as simple as presenting an ID card.

“They’re establishing more and more youth organisations, where Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots are participating together,” Silman said.

“Cyprus is too small to be divided.”

Despite the existence of the crossings, the two communities still live apart. The invasion turned Cyprus into an island of displaced people, with more than a third of Cypriots forced from or fleeing their homes in 1974.

The Varosha that Fialas and Toumazis knew is now a ghost town and a symbol both of displacement and decades of failed diplomacy.

Toumazis left Cyprus to study abroad and never moved back. He has no plans to mark the anniversary.

“I don’t see why we should celebrate,” he said.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP