‘He made me wear white,” says Fran Lebowitz, down the phone from New York. The writer is talking about the day her close friend, the photographer Peter Hujar, shot her for Portraits in Life and Death, the only book he ever made. “Peter was very specific. It was in my apartment which was the size of, I don’t know, a book. And the light was a big thing – as it was with all photographers, back when they were actually photographers.”

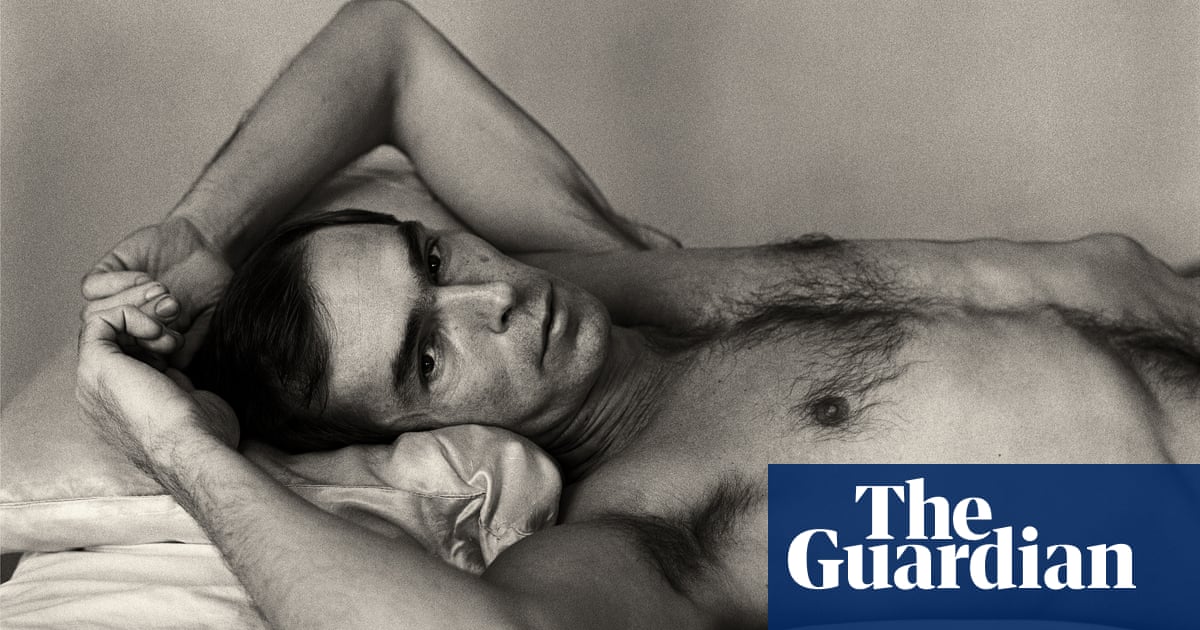

This week, the picture of a 24-year-old Lebowitz smoking a cigarette, slightly slumped, in a white shirt and tight white trousers on the arm of a settee, goes on show at the Venice biennale, alongside the 40 other pictures from Portraits in Life and Death. Twenty-nine of them depict artists, writers and performers Hujar knew and admired from the downtown scene of 1970s New York – many of them reclining in a state of reverie that seems completely un-posed. There’s the writer Susan Sontag, supine on a bed with a pensive expression; the drag artist and underground film star Divine off duty and resting on some cushions; nightclub dancer TC, topless and drowsily seductive; poet and dance critic Edwin Denby with his eyes meditatively closed, his wrinkles mirroring the rumpled duvet behind him.

The book then cuts to a memento mori: a dozen startling shots of 17th-century skeletons in their graves, taken in 20 minutes when Hujar visited the catacombs in Palermo, Italy, in 1963. They seem to suggest that everyone pictured in the book is dying, the photographer and the viewer, too. In fact, Hujar died of Aids in 1987, aged 53. As Sontag says in her foreword, written in hospital while she was being treated for breast cancer: “We no longer study the art of dying, a regular discipline and hygiene in older cultures; but all eyes, at rest, contain that knowledge. The body knows. And the camera shows, inexorably.”

Published in 1976, Portraits in Life and Death got just four reviews, the most-high profile being in the Village Voice. It failed to sell many copies. Today, however, it is recognised as not only a priceless document of a vanished culture, but as a collection of some of the finest portraits ever taken. Hujar insisted on printing all his pictures himself, and his meticulous efforts in his darkroom on Second Avenue resulted in black-and-white images that marry psychological acuity with flawless technique. “There’s a richness about the shades of grey he coaxes out of each print,” says Grace Deveney, curator of the Venice show. “And the longer you look, the more you see.”

“He made me conscious of the importance of the photograph as an object – a print to be held, examined and appreciated,” notes Vince Aletti, photography critic of the New Yorker, and another of Hujar’s close friends. “A photograph is not just a picture on a piece of paper. It has variations of size, weight, tone, texture and clarity that can vary from print to print. I never thought much about these things before I knew Hujar. Now I can’t forget them.”

Hujar’s reputation has risen in the past couple of decades. Many people first encountered his work on the cover of I Am a Bird Now by Anthony and the Johnsons, a stunning shot of the trans Warhol superstar Candy Darling in a hospital bed as she was dying of lymphoma aged 29. Another classic Hujar image, a man’s face at the point of orgasm, is on the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s misery lit blockbuster A Little Life. Yet despite his work’s undeniable quality, Hujar never attained the success of his peer and rival Robert Mapplethorpe, not least because he had a habit of infuriating anyone who could have helped him.

“He was sitting on a lot of rage,” says writer Stephen Koch, who was executor of his estate. As Lebowitz recalls: “I used to admonish him, ‘If someone is going to give you a show in Paris, don’t hit them over the head with a bar stool.’” Lebowitz is referring to an actual incident in which Hujar attacked two gallerists keen to exhibit his work. After Hujar died, Koch found a letter from the famous photographer Richard Avedon stressing how much he admired Hujar’s work and inviting him to get in touch. “Needless to say,” says Koch, “it was never answered.”

The reasons for this self-sabotage lay in Hujar’s childhood. “Peter was a born member of the underground,” Koch says. “He was a Manhattan street urchin. His mother was a waitress, his father was a bootlegger who abandoned her when she was pregnant, so she was without resources to raise him.” Hujar’s family were part of an influx of Ukrainian immigrants who came to the US after the second world war. His lack of English initially made his teachers think he had learning disabilities. He was brought up by his grandparents in rural New Jersey, but after his grandmother died, his mother moved him to Manhattan. Hujar left home at 16 after suffering violence and abuse during his teens.

Having experimented with his mother’s camera, he enrolled as a photography student at the School of Industrial Art. With the encouragement of his teacher Daisy Aldan, of whom he took one of his earliest great photographs, Hujar launched himself into the world of commercial photography. “His first job was walking the boss’s dog,” Koch says. “But he learned very sophisticated photographic techniques.”

Hujar also became immersed in New York’s art scene – a small world according to Lebowitz. “Like really small,” she says. “The whole New York art world would fit in one restaurant.” Aldan, who was also a poet, held salons at which Hujar met the likes of the poet and critic John Ashbery and the painter Helen Frankenthaler. He had a relationship with Paul Thek, the painter and sculptor who is photographed in Portraits in Life and Death. The pair were filmed by Andy Warhol for a 1964 project called The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys. Despite this accolade, and the fact that almost everyone considered him handsome, Lebowitz says: “Peter was very insecure about his looks – which were dazzling, by the way.”

“He was immediately someone I could have a crush on,” agrees Vince Aletti. The friendship between Aletti and Hujar is palpable in Portraits of Life and Death: Aletti looks relaxed but watchful, his moustache and open shirt embodying the hip gay look of the day, the watch on his hairy forearm another nod to the passing of time. Meanwhile, the poet Anne Waldman is photographed crashed out on a patchwork quilt, her Mandarin Chinese robe spread around her. “I felt honoured to be included,” she says. “I also felt he could really see me.”

Aletti lived across the street from Hujar, took him to record industry parties, and spoke to him most days. This sense of an artistic community or tribe is one of the most appealing things about Hujar’s work, and it isn’t hard to see where the need for it came from. “A lot of the people around Max’s had had horrible childhoods,” says Lebowitz, referring to the restaurant that was the scene’s nexus. “People who were not just a misfit in their little town, but who were thrown out of the house – or who never had a house to be thrown out of.” Hujar was astonished when Lebowitz took him to her family’s home in New Jersey, because it was so far from his own experience. “He had never seen a middle-class suburban house,” Koch says. “A two-car garage, a lawn, a washing machine. He was amazed.”

Waldman vividly describes a downtown Manhattan neighbourhood that was a ferment of both radical art and radical politics: “You could wake up in the morning and see WH Auden jogging a little further down the block.” Hujar wasn’t a political animal – though he photographed an early poster for the Gay Liberation Front advertising New York’s first ever Pride march in 1970. But he was fully engaged in everything else the underground had to offer. His recreational activities ranged from avant-garde theatre to cruising the Chelsea piers for anonymous sex. He once told Lebowitz that he had probably had sex with 6,000 men, but that he hadn’t much enjoyed it, explaining: “It was just my way of getting close to people.” Hujar once smuggled Lebowitz into a gay S&M club so hardcore that she could only stand it for half an hour. “It was too brutal. I remember saying to Peter, ‘If everyone else knew what was going on down here, they would send in the national guard.’”

Portraits in Life and Death was never intended to encapsulate an artistic era – the subjects were just people Hujar knew and was drawn to. Yet it captured a huge family of poets, composers, artists and drag queens engaging in creativity for its own sake rather than due to any commercial imperative, another reason why the book has such a charge. It is also one of many great works that underline the destruction wreaked by the Aids crisis. After Hujar was diagnosed on 1 January 1987, he never took another picture. When he died, on Thanksgiving Day later that year, his friend the artist David Wojnarowicz (who would himself die of Aids in 1993) took some shattering photographs of Hujar’s withered body in a hospital bed. It’s hard not to think of them when you see the skeletons in Portraits in Life and Death.

Hujar predicted that his work would become famous after his death, and his friends have mixed feelings about this prescience. “I absolutely don’t care,” says Lebowitz. “Peter was practically starving to death in his life. And see how expensive his work is now. It’s of no use to Peter.” Aletti agrees. “It’s sad that it’s happening without Peter here to appreciate it and benefit from it. But I’m so glad to see Peter’s name as part of the conversation about photography now, when he was hardly acknowledged or even known in his lifetime.”

Hujar’s sensibility is so finely honed, his portraits so intimate, his hand-crafting of the images so lovingly precise, that he still feels astonishingly present in Portraits in Life and Death. “Peter and I walked around together all the time,” Lebowitz says. “He would just suddenly stop in the street and say, ‘Look at the light on that fire hydrant. Look at that light!’ I don’t think I ever thought about light before I knew Peter. And I’ve been highly aware of it ever since.”

-

Peter Hujar: Portraits in Life and Death is at Istituto Santa Maria della Pietà, Venice, 20 April to 24 November

![Sunny Leone reacts to Bihar, who has claimed she is his mother [Exclusive] Sunny Leone reacts to Bihar, who has claimed she is his mother [Exclusive]](https://st1.bollywoodlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Sunny.jpg)