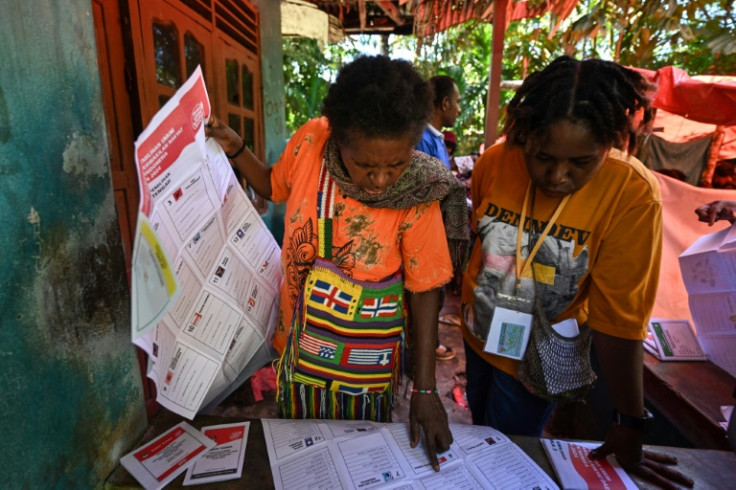

From makeshift bamboo polling stations in remote tribal areas to the flooded streets of the capital, tens of millions of Indonesians went to the polls Wednesday in one of the world’s biggest one-day elections.

The Southeast Asian nation’s election is a mammoth exercise in logistics spanning three time zones with ballot boxes transported by truck, boat, helicopter, horse and even ox-cart.

The election was just the fifth since the fall of the Suharto dictatorship in 1998 and voters across the vast archipelago of more than 17,000 of islands were determined to cast their ballots.

In remote Central Papua’s Timika, residents queued at a bamboo-framed shelter covered in a blue tarpaulin roof to register before voting.

“I will vote for the one who would be the best to develop Papua,” 19-year-old student Daton, who only gave his first name, told AFP in the province where separatists have waged a decades-long insurgency.

Police armed with assault rifles stood guard nearby but with around a quarter of a million officers and soldiers deployed, and 800,000 polling stations, their resources were spread thinly.

More than 3,300 kilometres (2,000 miles) to the west, torrential thunderstorms delayed the start of voting in parts of the capital Jakarta but the rains failed to dampen the hopes of voters as they queued to cast their ballots.

Floods forced the relocation of some polling stations across the sprawling megacity of 10 million, with some residents still waiting to vote two hours after polls were due to open.

“We didn’t expect the polling station to be flooded like this,” said 30-year-old hotel worker Afrian Hidayat.

In some areas workers used pumps to drain flooded polling stations while others wearing green T-shirts that read “not voting is not an option” waded through the water to carry ballots and electrical equipment to safety.

In Jakarta, like other parts of Indonesia, election officials had wrapped the ballot boxes in plastic as a precaution against inclement weather.

“We have to move the polling station indoors. We knew it was going to rain but we didn’t expect it was going to rain like this,” said Audy Adam, 34, an election official in Jakarta’s Kebon Sirih district.

As the rain eased, voters lined up at a makeshift polling station on the banks of the capital’s Ciliwung river.

“My hope for this year’s election: I hope… the elected leader will be a trustworthy leader as the people wish for,” said Nindya Santi, 26, who works at a government-owned-company.

Like most voters asked by AFP, she wouldn’t disclose who she cast her ballot for.

Driver Budi Antono, 57, was waiting to vote at a polling station which opened two hours late, with water pooling in a nearby alley.

“I hope the election will be honest and fair, not like the previous elections. Because the voting is for a better Indonesia,” he said.

In a country where millennials and Gen-Zers make up more than half the electorate, university student Muhammad Ariq, 20, said he had used TikTok, Instagram and X, formerly Twitter, to do research on the candidates.

“As a first-time voter I am a bit nervous, but I’m also excited,” he said.

In western Java, some members of the indigenous Baduay tribe which largely shuns technology and the trappings of modern life examined the lists of candidates before voting in their village of Kanekes.

On the mainly Hindu central resort island of Bali, residents wearing colourful traditional sarongs waited to vote, with some displaying their inked fingers after casting their ballots.

And in far western Sumatra, prisoners at a jail in Banda Aceh queued to vote under the watchful eye of police, who like members of the military are barred from voting.

A so-called “quick count” is expected to give an indication of the national results later Wednesday.

And for despondent losing candidates, a hospital in Makassar, South Sulawesi has prepared VIP treatment rooms with psychiatric staff on hand to help them come to terms with the results, local media reported.

“The healing period varies depending on the patient’s condition,” Wawan Satriawan, public relations coordinator for Dadi Regional Special Hospital, told CNN Indonesia.

“Some people are usually treated for a period of two weeks, some also take months.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP