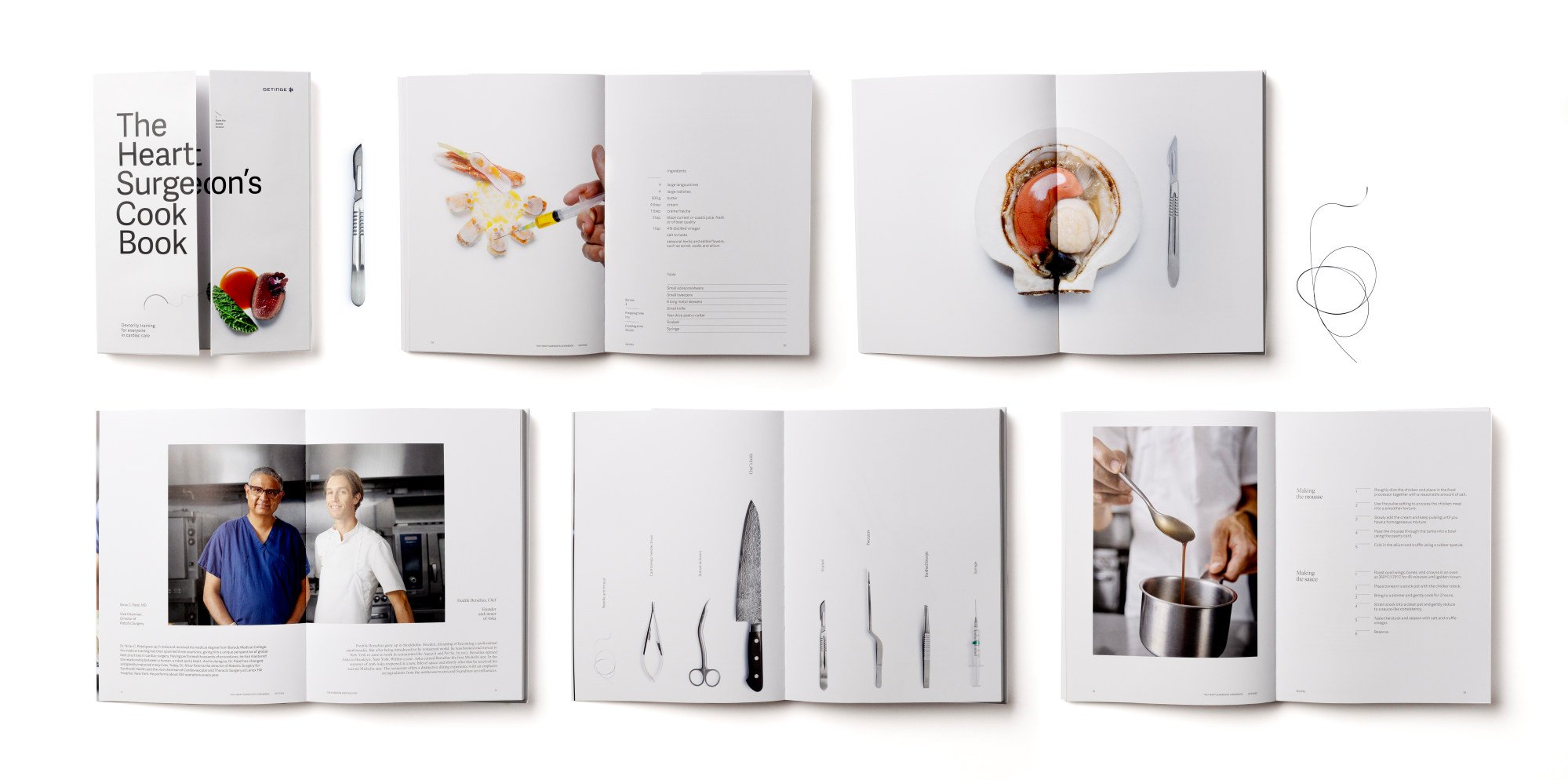

But rather than being a collection of recipes for heart health or post-operative care, this book has been specifically created for trainee surgeons to improve their dexterity.

Of course, it is not only surgeons who can enjoy the recipes, which have been developed by Swedish chef Fredrik Berselius, of two-Michelin-star Aska, in New York. The nine complex and intricate dishes could be followed by any home cook up for a challenge.

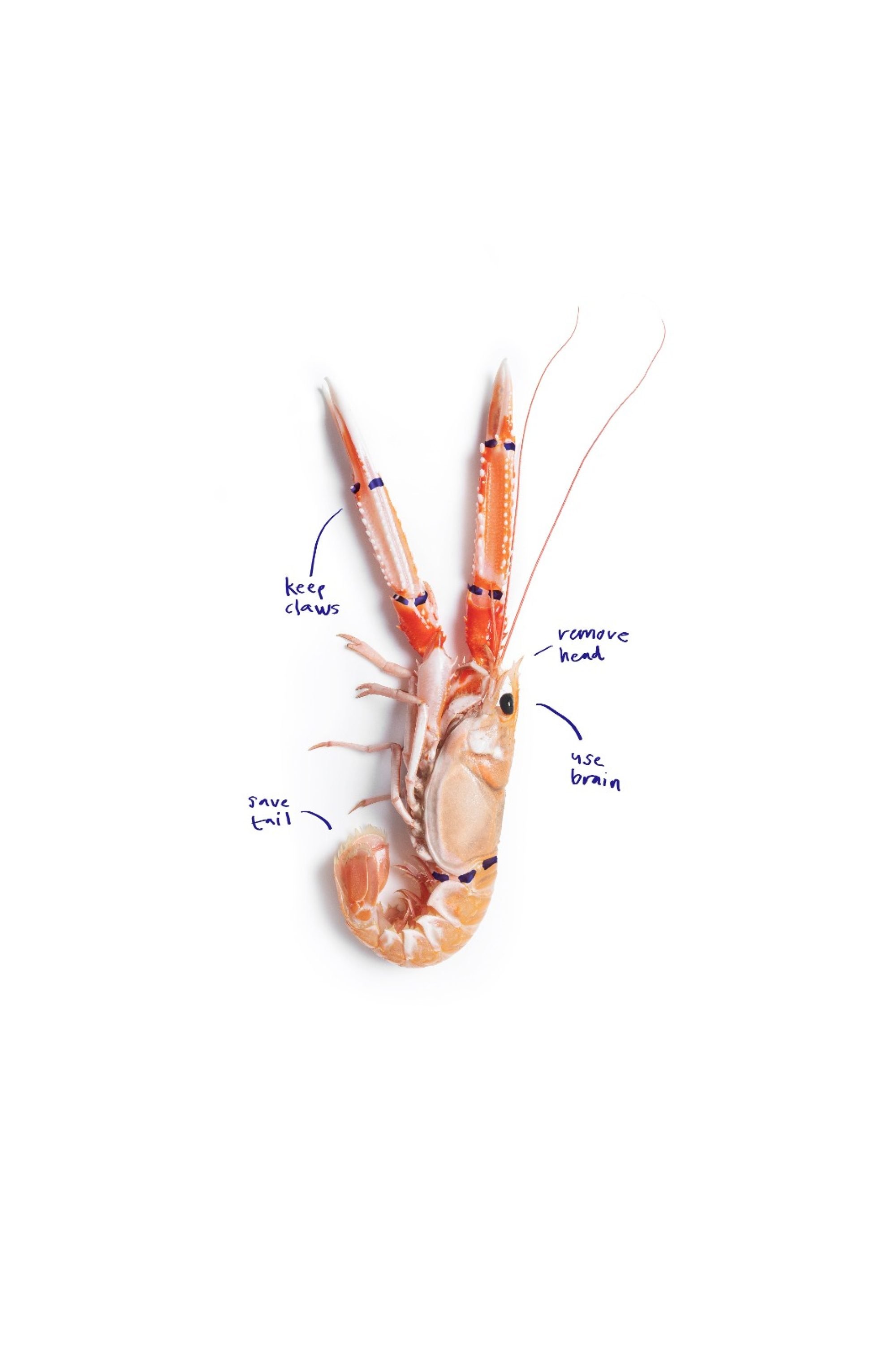

Recipes include a beautifully presented “rose” of kingfish with green gooseberry; langoustine tail and claw with blackcurrant; and ice cream and meringue with lavender cream and honey.

She’s demystifying ‘amazing’ regional Chinese food for the world to enjoy

She’s demystifying ‘amazing’ regional Chinese food for the world to enjoy

For all readers, the strikingly illustrated book (which includes X-rays of a chilli and a pod of peas) provides a captivating look into the unexpected overlaps between surgery and cooking – preparing dinner may never be quite the same again.

When Swedish medical equipment company Getinge contacted Berselius about its idea for the cookbook, he immediately cancelled his holiday to work on it.

“My first thought was, ‘Why hasn’t anyone thought of this sooner’?” he says. “It made me take a step back and look at what we do every day in a different light.

“How we use our hands and fingers is so important in our work, in cooking at our level. Touch is critical – from putting flowers on a dish, which is an obvious and easy way of looking at it, to working with the anatomy of a piece of meat or a vegetable. It helps you be in tune with what you’re working with.”

The team introduced Berselius to Dr Nirav Patel, director of robotic cardiac surgery at Northwell Health and vice-chairman of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, both in New York.

In their initial phone call, chef and surgeon found unexpected similarities between their professions. Berselius first described how chefs have to be aware of, and respond to, delicate variations in produce.

“I explained how, for example, from summer to winter, the size of a fish may change, and how even though two fish may look more or less the same, there can be minute changes in the density of the flesh,” he says.

“Immediately Dr Patel jumped in to say that surgery is exactly the same. There are nuanced differences in the thickness of the heart’s auricle wall, for example, and that surgeons have to be aware and feel their way around, and be conscientious of how they cut. I know nothing about heart surgery but the conversation was fascinating.”

Berselius realised that in addition to culinary training, much of a chef’s knowledge of butchery of fish, poultry and meat comes from feel and experience.

Chefs look for, or feel for, the natural separation in a loin, for example. When filleting or cutting a piece of meat, how and where a chef cuts can make a more attractive portion, so following the natural separation along the muscles can make a difference to the final product.

His discussions with Dr Patel also highlighted the commonalities between creatures.

“Chickens, ducks, rabbits, deer, cows – these all have a rib cage, head and neck, and a heart and liver. Even fish have a sort of rib cage and meat with muscle fibres. How we work translates from animal to animal,” says Berselius.

“Of course surgical work is much finer, but stitching, for example, is the same in principle in the human heart and for the skin in the roasted quail with truffle and ramp.”

For the cookbook, Berselius chose recipes, some based on those served at Aska, by looking at cooking from a surgeon’s point of view – recipes that would be interesting, accessible and fun while also requiring deft use of the hands and fingertips, as well as surgical tools such as a scalpel, syringe or tweezers.

Over the course of several phone calls with Dr Patel, Berselius tweaked the recipes, adding elements that would further test surgical dexterity or highlighting certain aspects in the accompanying text.

In the recipe for sea scallop and turnip in warm broth, Dr Patel comments: “Knowing the anatomy of the scallop to make a precise incision of the adductor muscle [the most commonly eaten part] to remove it intact is like removing mass in surgery en bloc without disrupting it. The cork cutter movement is used to make precise holes in the heart or great vessels.”

The book also has a section on repetitive practice – something else that surgery and cooking share – with exercises including peeling a blueberry with a scalpel without harming the pulp, removing all the seeds from a strawberry without nicking the berry, and cutting an orange segment then stitching it back together using a needle and thread.

“It’s a big part of what we do, and is a challenge,” says Berselius. “For young cooks, repetitive movements or tasks can be exhausting, daunting and boring – they want to move on and always be learning something new. But the more you do something, the more you start looking at it differently.

“The 10th dumpling may be boring, but by the 1,000th you may have learned to love the repetition.”

Berselius has had many years of appreciating the meditative aspects of cooking. He moved to New York from Stockholm, Sweden, in 2000, and worked in restaurants across the city including Aquavit and Per Se.

He opened Aska (“ashes” in Swedish) in Brooklyn in 2012 before moving to a bigger, two-level space in 2016, where it soon earned its second Michelin star.

The restaurant serves seasonal contemporary Scandinavian tasting meals.

With a grandfather who was an athlete, Berselius has long been fascinated by how food affects performance, sleep and mood. The dishes he serves at Aska – and those that appear in the cookbook – call for high quality, largely healthy ingredients.

“I always wanted my cooking in the restaurant to run in parallel to my own well-being and life. The dishes at Aska are low in sugar, with good fats and dairy.

“I eat the same ingredients at home – perhaps not the Norwegian langoustines and truffles – with my family … I source ingredients from the same places, usually the farmer’s market for vegetables, and never eat fast food,” he says.

“There’s a correlation between what you serve, how you source it and how you feel. I want guests to feel good when they leave the restaurant, and after they eat the dishes in this cookbook,” he says.