Chef Adam Wong Lung-to, anointed Yeung’s culinary heir to carry on his legacy, knows he has big shoes to fill.

Wong, who has been at Forum Restaurant for 32 years, is determined to honour his si fu (teacher) by preserving his signature dishes such as the Forum fried rice, tangerine peel sweet and sour pork and, of course, the braised abalone dishes.

“They won’t be changed because they are so iconic,” Wong says. “Our diners come because they want to eat these traditional dishes. If they wanted fancy new tastes, they could easily go to a contemporary fine-dining Western restaurant.”

It wasn’t because his mentor forbade changes, he says. On the contrary, he remembers him as a very open-minded chef who loved Eastern and Western cuisine, and was open to trying new ingredients for his dishes.

“He was the one who introduced eating abalone the Western way – with knife and fork,” he says.

One of the things his mentor drilled into him was the need for the best ingredients. The restaurant uses only premium dried abalone from Japan, many of which were stockpiled by Yeung years ago. In addition, plump sea cucumbers or goose webs make for perfect companions to the abalone in the restaurant’s signature dish.

Wong recalls occasions when, in their daily discussions, new ideas such as using Wagyu beef for stir-fried beef with vegetables would crop up.

“That didn’t quite work out initially because we thought we should use the best A5 grade of Wagyu and it turned out to be too fatty. But his thinking was, ‘who says you can only use normal stir-fried beef with vegetables’?” he says.

A dish that worked out better is Forum’s unique tangerine peel sweet and sour pork. “When I broached the subject, his response was ‘there’s no such thing’. Five minutes later, he asked me why I was still sitting there and not in the kitchen trying it out! We discovered that the fruity tangerine peel enhanced the pork flavour.”

The experimentation has also given birth to what is arguably the only three-Michelin-star cheong fun, or steamed rice roll, which Wong presents with baking paper and wooden sticks, much like the street hawkers used to do – only using premium ingredients.

“Of course, there are also a lot of ingredients available now that we didn’t have before and sometimes we add them to enhance the dishes, such as truffles or truffle oil which we have added to our stuffed chicken wings,” he says.

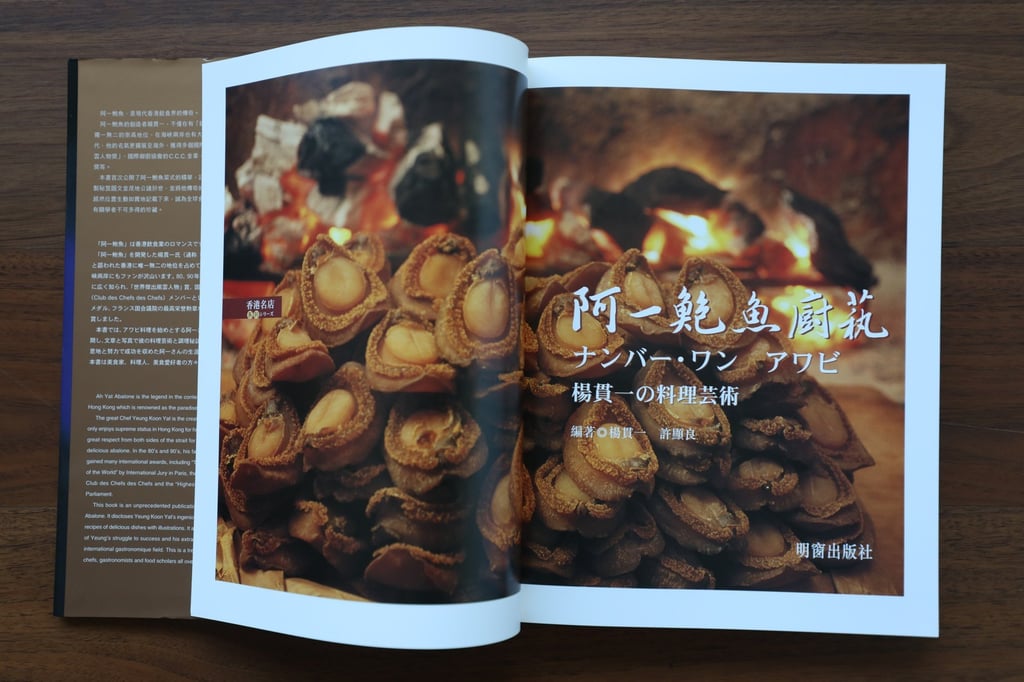

The close relationship between mentor and mentee over the past three decades is documented in a book whose name translates as Ah Yat, Disciple and Abalone. Wong turns to a page depicting a trip the pair took to Chongqing in southwest China.

“He suddenly asked me to prepare paper and ink for him. He said he wanted to write some calligraphy for me,” says Wong, pointing to the words that he eventually wrote: “Wong Lung-to, the heir of Ah Yat Abalone and my beloved disciple, is the only one mentored by me forever.” Very large shoes to fill indeed.

Wong’s rise to “abalone prince” – a title bestowed on him by Yeung – did not come without hardship. His father died when he was very young, leaving his mother as the family’s sole breadwinner.

The family business was selling eggs and Wong recalls pushing his metal cart the 2 kilometres (1.3 miles) from the shop in Wan Chai to the suppliers in Sheung Wan to collect eggs and take them back to Wan Chai.

“It wasn’t too bad when the weather was good, but during rainstorms and typhoons, everything would get drenched. We didn’t have nice egg cartons then, everything was just in a big box, eggs would get broken,” recalls the 54-year-old.

Every customer is a Michelin inspector because they are who we cook for

The then-16-year-old decided he needed something more stable. While he wasn’t particularly enamoured with cooking, he turned to the industry he knew best – restaurants. He already knew some because he used to deliver eggs to them.

He eventually found a job at a clay pot restaurant in Kowloon.

The early days weren’t happy ones, and restaurant work was tough and demanding with staff often at the mercy of the head chefs. Wong recalls an incident when he left his station uncleaned to learn from another chef how to kill crabs.

“I returned within 10 minutes but my supervising chef had already cleaned everything. He asked me to mix some salt and when I was bending down he just squeezed the dirty water from the cleaning cloth over my head. He said if I didn’t do my work, he would have to do it for me,” he says.

Still, Wong stuck with the job for six years until the restaurant closed, working his way up to doing stove work. When he heard of an opening at Forum, he persuaded them to give him a chance.

Despite the opening being only for general kitchen staff who could step in to cover for anyone at a moment’s notice, the young man took the job.

“To me, every job is important. It doesn’t matter if you’re the cleaning lady or kitchen staff or the cook, everyone has a role to play. We always talk about teamwork nowadays. Similarly, to me, every customer is a Michelin inspector because they are who we cook for,” he says.

I have to do my best to maintain his standards. I’m so honoured to walk in his footsteps.

His hard work and uncomplaining nature did not go unnoticed by Yeung, as is documented in the book. After about 10 years of working at Forum, Wong was officially named Yeung’s disciple.

Wong himself has yet to take on his own disciple, declaring himself “too young” to do so, although he has identified one or two with potential.

For now Wong still has a mission. Although most executive chefs nowadays take on a more supervisory role – designing the menu rather than actually cooking – Wong still insists on personally cooking Forum’s specialities to honour his late mentor.

“Nothing beats the tried and the tested. That’s what people come to the restaurant to eat,” he says. “I always believe that you have to do the best in what you do best.” Wong points to how some wonton noodle shops stay popular for decades just by serving the best wontons and egg noodles.

Wong’s new book The World of Abalone Flavours was launched at this year’s Hong Kong Book Fair to commemorate the anniversary of his mentor’s death.

“I realised there are very few books about abalone from around the world. To many it is just a kind of seafood; it doesn’t come with certification. But there are so many different kinds of abalone from around the world – Middle East, South Africa, Australia, Indonesia, Mexico – all of them are really quite different,” Wong says.

His mentor’s advice remains stuck in his mind. Wong recalls one afternoon not long before Yeung death. “He was taking his afternoon rest and he suddenly gave me three pairs of glasses. I thought he wanted me to throw them away but he told me: ‘I have worn these glasses and I want you to have them because I want you to be able to see what I have seen through them’,” Wong says.

He adds: “I have to do my best to maintain his standards. He gave me so many chances, taking me with him to exchanges in other countries, trying new things, teaching me.

“Si fu is gone but he will remain forever in my heart. I’m so honoured to walk in his footsteps.”