UK lawmakers voted Friday in favour of assisted dying for terminally ill people in England and Wales, advancing the emotive and contentious legislation to the next stage of parliamentary scrutiny.

Campaign group Dignity in Dying hailed the result as a “historic step towards greater choice and protection for dying people”, but Christian Concern called it a “very Black Friday for the vulnerable in this country”.

MPs voted by 330 to 275 in support of legalised euthanasia in the first vote on the issue in the House of Commons for nearly a decade.

The result followed an emotionally charged debate that lasted almost five hours in a packed and hushed chamber, and as competing protesters made their voices heard outside parliament.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill now progresses to the next stage where lawmakers can propose amendments, a process likely to be vexed.

The legislation would then face further votes in the Commons and House of Lords upper chamber.

The process will likely take months and if it is ultimately passed then a change in the law is expected to be several years away.

The House of Commons last debated, and defeated, a euthanasia bill in 2015, but public support for giving terminally ill people the choice to end their lives has since shifted in favour, polls show.

A change in the law would see Britain emulate several other countries in Europe and elsewhere who allow some form of assisted dying.

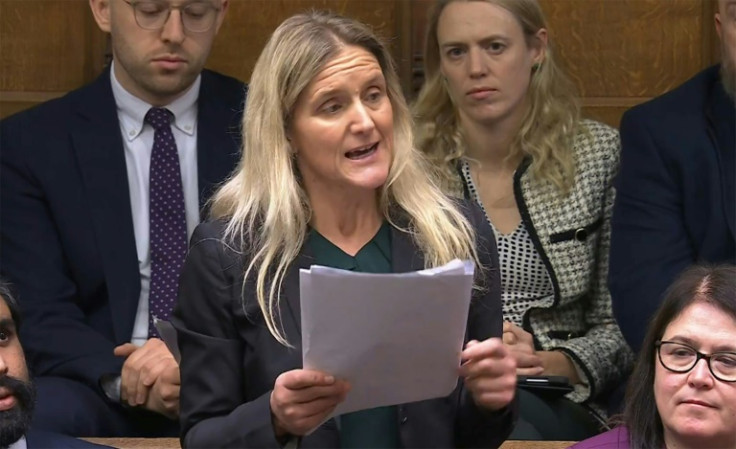

Labour MP Kim Leadbeater, who is behind the bill, told the debate that changing the law would give terminally ill people “choice, autonomy and dignity at the end of their lives”.

Advocates also argue that it would make some deaths less painful.

But other MPs expressed concern that people might feel coerced into opting for euthanasia, while some said they were worried it would discriminate against people with disabilities.

Opponents also worry that the healthcare system (NHS) is not ready for such a landmark change and that it could cause a decline in investment for palliative care.

“True dignity consists in being cared for to the end,” Conservative MP Danny Kruger said, urging colleagues to reject a “state suicide service”.

Outside, scores of opponents gathered, holding signs reading: “Kill the Bill, not the ill” and “Care not killing”.

A nearby gathering in favour of the legislation saw people dressed in pink holding placards with slogans such as: “My life, my death, my choice.”

After the vote crowds of supporters hugged Leadbeater.

“I know what it means to people. If we hadn’t achieved what we achieved today, I’d have let them down,” she said.

Broadcaster Esther Rantzen, who is terminally ill and has spearheaded the campaign for a law change, said she was “absolutely thrilled”, even though it was unlikely she would benefit.

She said she had been “very moved by the various doctors who took part, who gave painful but important descriptions of the kinds of death people suffer, which cannot be eased by even the best palliative care”.

The Church of England’s lead bishop for healthcare, Sarah Mullally, who had opposed the move, said that safeguarding the vulnerable “must now be our priority”.

“Today’s vote still leaves the question of how this could be implemented in an overstretched and under-funded NHS, social care and legal system,” she added.

Assisted suicide currently carries a maximum prison sentence of 14 years in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In Scotland, which has a separate legal system and devolved powers to set its own health policy, it is not a specific criminal offence. But it can leave a person open to other charges, including murder.

Leadbeater’s bill would allow assisted suicide in England and Wales for adults with an incurable illness who have a life expectancy of fewer than six months and are able to take the substance that causes their death themselves.

Any patient’s wish to die would have to be signed off by a judge and two doctors.

The measures are stricter than assisted dying laws in other European countries. Consideration is being given to a similar law change in Scotland.

MPs had a free vote, meaning predicting the outcome was virtually impossible.

Starmer voted in favour, as he did in 2015. His ministerial team was fairly evenly split for and against, parliamentary data showed.

AFP

AFP