The lone foreigner stands out.

But in Benson’s time Mengzi was better known than it is today.

Sited in the middle of an agricultural plain rimmed with mountains, 1,400 metres (4,500 feet) above sea level, it was home to a community of consuls and customs officers, railwaymen and writers, who lived and worked in buildings around a lake outside the city’s east gate.

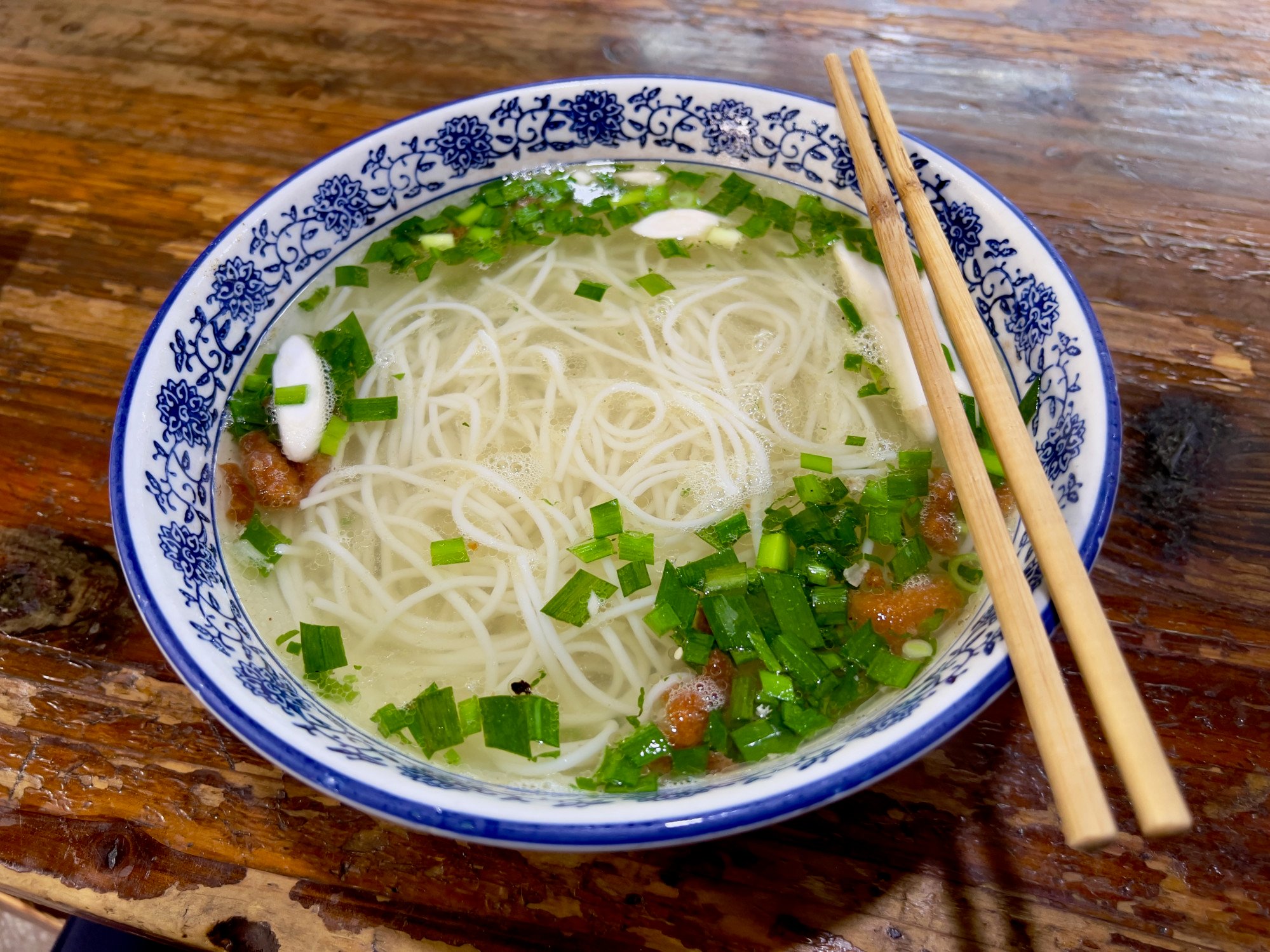

The city walls and gates are long gone, and rapidly modernising Mengzi has expanded far beyond its former limits. But now it is known for creating Yunnan cuisine’s oily across-the-bridge noodles, and not for much else.

The South Lake is still there, picturesquely crossed by causeways with dragon-back bridges, and there’s still evidence of Benson’s day around its shores and in nearby countryside.

Paul Doumer, governor general of French Indochina, wrote that Tonkin’s only value lay in the opportunity to expand French influence into Qing China and to increase trade.

Yunnan, he thought, was an El Dorado waiting to be exploited, yet France waited two more years to nominate towns where, under the treaty’s terms, the Qing would permit foreigners to reside and trade.

The foreigner-run Imperial Maritime Customs Service duly opened its Mengzi office in 1889.

It was “a fine well-treed compound full of birds and shade and the sweeping lines of eucalyptus trees and big rose trees”, wrote Benson.

One customs building remains. Now open as a museum, it was labelled on historic maps as the post office, because until 1911, the Maritime Customs ran the Great Qing Postal Service, too.

Its roof of Chinese tile with curved eaves contrasts with its European-style doors and shutters. Inside there are displays of photographs from its heyday, books of customs regulations in English, Chinese documents in elegant calligraphy with bold red seals, and the pistols and swords then necessary for tariff enforcement.

A map shows the locations of French, British, German, Italian, Norwegian, American and Japanese businesses that opened up in Mengzi between 1899 and 1922.

A list of customs commissioners includes one C. H. Brewitt-Taylor, who reported that Mengzi’s principal exports were tin and opium. “I hope business will look up in the presence of a favourable harvest,” he wrote in August 1906.

[Mengzi] had hardly any other function in human affairs but to be a smuggler’s town

From 1937, as the Japanese invasion pushed Chinese institutions ever further south, Peking University combined with two others to form the National Southwestern Associated University, and relocated to Yunnan.

Its law and literature departments ended up briefly in Mengzi, using the customs compound as premises.

One transplanted lecturer was William Empson, noted English literary critic and poet. Mengzi, he wrote, “had hardly any other function in human affairs but to be a smuggler’s town”.

He gained first-hand experience when he was robbed by bandits during an ill-advised promenade outside the city at dusk, although seeing he was suffering from cramp, his assailants also offered to help get him to his destination.

Some outlaws had, at least in their own minds, high standards of morality, one band issuing instructions that female students should not be allowed to bathe in the lake.

The university also took over rooms in the former premises of a Greek company called Kalos, a short walk around the lake, whose red-tiled, low-pitch roofs and yellow walls give them a distinctly Mediterranean look.

What’s now the Mengzi Sub-campus Exhibition Hall of National Southwestern Associated University museum makes much of the impact of the university’s sojourn with displays of waxwork students ardently arguing.

To Doumer’s disgust, the large majority of what trade passed through the region remained British, arriving at Haiphong by steamer from Hong Kong and then passing up the Red River by smaller boat to Manhao, two days south of Mengzi by pack animal.

Their cottage-like office, briefly turned into a wine bar but now closed again, still stands at the east side of the lake, and the remains of the French consulate are just a little to the south of the customs office.

The sunny courtyard surrounded by more part-Chinese, part-European buildings is now an active community centre, but its walls are hung with historic photographs of Frenchmen in solar topis.

Of the French consulate’s gardens, only a fragment remains, just west of the customs house, where retirees still play croquet with considerable skill, but now in the Japanese version called gateball, and on an artificial lawn.

The French-built one-metre-gauge railway line brought Mengzi prosperity, through those well-paid engineers, and then ensured its return to obscurity.

The railway opened in 1910. The ride from Haiphong to Kunming took three days as it was too hazardous to travel at night, and passengers spent two nights in notoriously flea-infested inns, run by Greeks.

Benson and Empson both thought the journey tedious, although others were awed by the rugged scenery and the thousands of bridges and tunnels required.

Instead of following the pack route from Manhao, the line crossed the border further east, at Hekou, and Mengzi was bypassed until 1921, when the Chinese opened the 600mm-gauge Gebishi Line, one of the first private railways in the country, to bring tin up to the main route.

Our Chinese railway company manages to connect with the afternoon French main-line train by launching a little expedition … every morning on the doubtful hour’s trip

The last of this line was closed in 2003, and the station at Mengzi and its historic outbuildings were turned into offices. Remnants of the track remain at a now permanently open level crossing immediately to the west of the old station, in Bei Dajie.

Today it is merely 20 minutes by taxi from Mengzi to the junction with the main French line at Bisezhai, past greenhouses in which grow peppers and flowers. But the journey was more problematic in Benson’s time.

“Our Chinese railway company manages to connect with the afternoon French main-line train by launching a little expedition between seven and nine every morning on the doubtful hour’s trip to the edge of the valley. True, there is supposed to be a Chinese train between two and four, but it generally misses the French train.”

The engine often required several attempts to get up the hill.

“Passengers thus find themselves reappearing at Mengtsz [sic] platform, to the surprise of the friends who came to see them off.”

Small and sleepy Bisezhai was – rather improbably – known as the “Little Paris of the East”, according to visitor information signs around its two old stations. French, British and American merchants all had premises here, and more than 3,000 porters handled cargo day and night.

Until 2005, it was still possible to ride from Bisezhai down to the border at Hekou in carriages full of Miao and other colourfully dressed minority people.

In 2011, with only freight services remaining, the station was deserted, and today both lines are gone, save for a small section of the Gebishi Line used for tourist excursions from and back to Jianshui, further west.

The French station is locked, and the hands of its Paris-made three-faced clock have fallen off and been drawn back in marker pen.

But the small section of track that has been retained for historical reasons is now busy with Chinese wannabe influencers taking selfies, and there’s a pleasant 100-metre stroll down the old main-line route to the Chinese station, past water towers, engineering offices, the remains of an old Greek-run hotel, a cafe with railway-style cast-iron benches, and a still-usable red-clay tennis court.

An ancient 600mm-gauge steam engine, made in the United States, rusts gently on a siding.

The opening of the railways meant that foreign trade mostly bypassed Mengzi. Between 1908 and 1911, the number of boats on the Red River dropped by 80 per cent, and the number of pack animals fell from more than 60,000 to barely double figures.

The engineers left, the customs staff was reduced to one person, the consulate closed, and the universities returned to their original premises.

The world mislaid Mengzi again.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/02/12/709/n/43463692/affdf68367acc608c50d79.20958537_.png)