With just five keystrokes, the computer’s on-board input method editor (IME) – a program that transforms QWERTY keystrokes into Chinese characters – has all it needs to produce the beloved stanza.

As most mainland Chinese computer users know, the most popular IMEs today are based on pinyin. This is true for desktop computing as well as for mobile applications.

“Pinyin input”, as it is often abbreviated, dominates.

It has not always been this way, however. Pinyin input is a newcomer in the history of Chinese computing.

From the invention of the first Chinese computer, in 1959 – the Sinotype, developed at the Graphic Arts Research Foundation by Massachusetts Institute of Technology electrical engineering professor Samuel Caldwell – all the way to the 1980s, pinyin input was dismissed as the worst of all possible approaches to Chinese computing.

Instead, the opening decades of Chinese computing were dominated by what are called “structure-based” input systems: systems that use Latin alphabetic letters and Arabic numerals to describe, not the sound of Chinese characters, but their shape.

Pinyin’s late rise wasn’t for lack of some powerful advocates, that much is certain. In fact, there was enormous pressure in favour of what we might call the “pinyin-isation” (pinyinhua) of Chinese information technology.

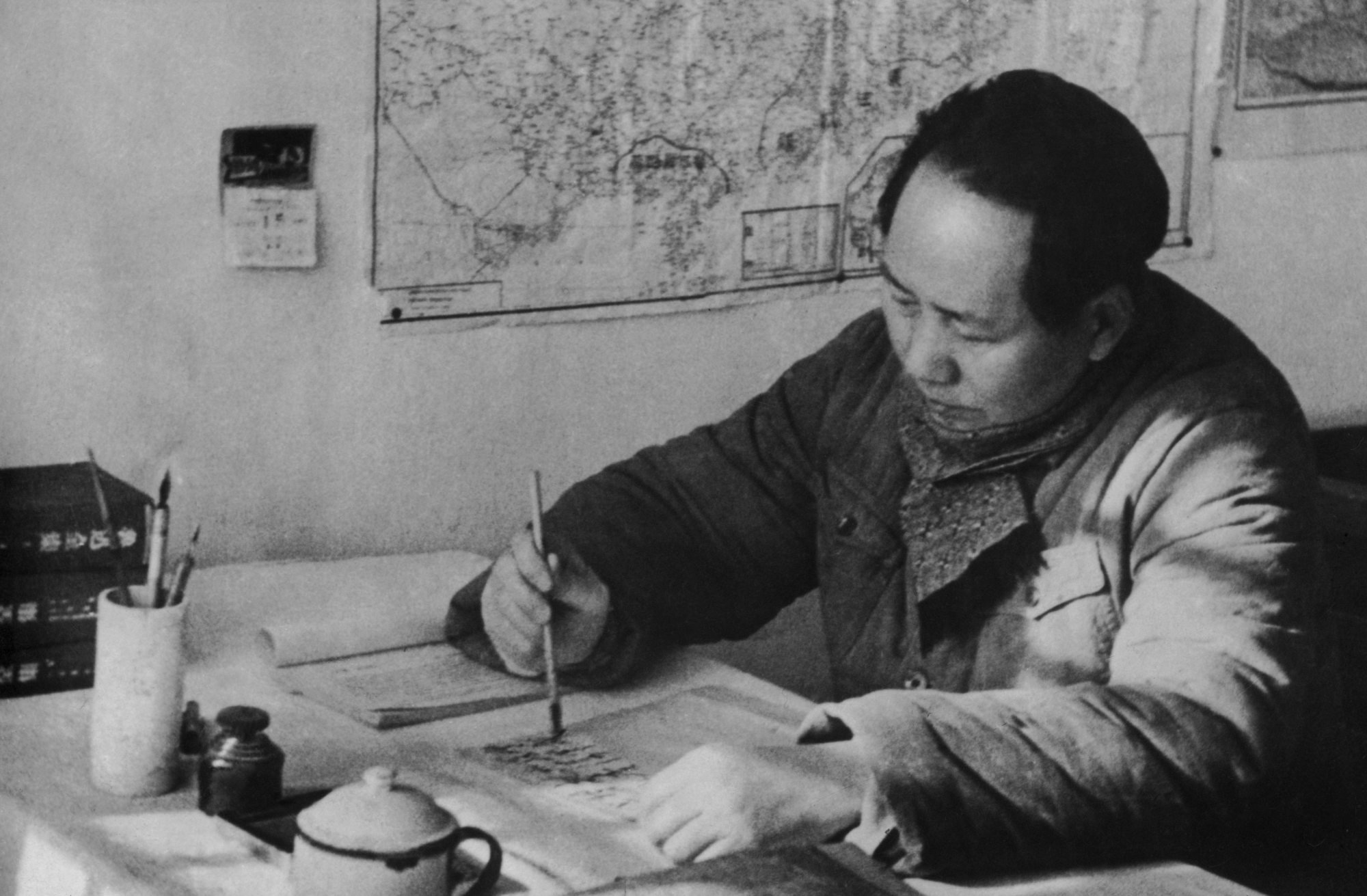

This pressure was exerted both from abroad, in countless efforts by foreign missionaries to phoneticise Chinese, and from within China, up to and including Mao Zedong himself, who once called for the abandonment of Chinese characters and their replacement with a fully phonetic orthography (along the lines of Vietnamese).

In the post-Mao period, pinyin steadily became a feature of everyday life, serving as a kind of parallel writing system that ran alongside character-based Chinese writing.

When Chinese toddlers learned to read and write Chinese characters, for example, they often learned pinyin first, to assist them with the memorisation of standard, non-dialect pronunciation.

Meanwhile, as people navigated their everyday lives, the sight of pinyin became more commonplace, whether on street signs, bus schedules, book covers or elsewhere.

Given pinyin’s widespread familiarity and political backing, then, surely it must have been a shoo-in to become China’s go-to solution for Chinese input, right? Wrong.

To the contrary, computer engineers long considered pinyin entirely unworkable for the purposes of inputting Chinese on computers. And for good reason: pinyin input was terrible.

From a technological standpoint, at least three intractable problems bedevilled pinyin. First, pinyin spellings were long – almost always longer than those found in structure-based input systems. Consider the character 电 (dian, “electricity”).

While the pinyin spelling of this character contains four letters – D-I-A-N – many of the most popular structure-based input systems from the 1950s to the 80s required only three keystrokes.

In the Five-Stroke input method (Wubi shurufa), 电 could be inputted with the three-key sequence: J-N-V. The same was true for Cangjie input (L-W-U), Yi input (R-G-D), and dozens of others.

Moreover, pinyin input was ambiguous. Dian also corresponds to more than two dozen other Chinese characters. Even after typing out the letters D-I-A-N on one’s QWERTY keyboard, a user still faced the task of trying to find which “dian” they wanted.

Was it 点 (“dot”), 店 (“shop”) or otherwise? For more “commonly used” dian characters, these were likely to be found at or near the top of the on-screen pop-up menu.

But if the user wanted one of the less common dian characters (滇, for example, an abbreviation for Yunnan province), they would need to scroll through a series of pop-up menus to track down their target.

By comparison, structure-based input sequences were far more streamlined, with each alphanumeric code corresponding to far fewer potential characters, and, in some cases, only one possibility.

One of the earliest experiments with pinyin input is found in the work of Shanghai engineer Zhi Bingyi. Like others working on Chinese computing in the 1970s and early 80s, Zhi’s “On-Site Coding” input system (or “OSCO” for short) was not a phonetic system but a structure-based one.

OSCO input used letters of the Latin alphabet to describe the structural shapes of Chinese characters rather than their sounds.

At the same time, Zhi dedicated a small subset of his code to what he called “character compound codes” (cihuima) – also called “OSCO Quick-Codes”.

These were special-purpose two-letter sequences that enabled a computer user to input not just one character at a time, but two-character compounds. A large portion of the modern Chinese vocabulary is formed of two-character clusters, such as “student” (xuesheng) and “work” (gongzuo).

To enter the two-character Chinese word for “safety” (安全, anquan), for example, an OSCO user could type in “A-Q”, the “A” corresponding to the initial pinyin letter of an and “Q” to the initial pinyin letter of quan.

To input the two-character compounds “extremely” (非常, feichang) and “revolution” (革命, geming), meanwhile, the Quick-Codes were “F-C” and “G-M”, respectively.

The reason Zhi’s Quick-Codes worked is, counterintuitively, because they broke the rules of pinyin. “AQ”, “FC”, “GM” and so forth are not valid pinyin – something that even a Chinese kindergartner could tell you.

It was precisely because of this violation, however, that the codes worked. Insofar as GM, FC and AQ cannot possibly be mistaken for any “real” pinyin value, the computer can treat them, with complete confidence, as an input sequence whose goal is to retrieve a two-character compound from memory.

And while there are dozens of Chinese characters that correspond to the pinyin spellings of “an”, “quan”, “fei”, “chang” and so forth, there are far fewer two-character Chinese words whose characters start with “a” and “q”, “f” and “c”, etc.

Entering a two-character compound is far faster, it turned out, than entering two characters one after the other.

Zhi’s experiment revealed a redeeming quality of pinyin input that others had overlooked: its ability to enter many Chinese characters at once.

By and large, all structure-based input systems had from the 1950s been fine-tuned to inputting individual Chinese characters. Indeed, inventors of structure-based input methods spent years tweaking their system to ensure that each alphanumeric code corresponded to the smallest number of Chinese matches as possible.

They wanted their systems to be fast, after all, so ambiguity was the enemy. Zhi’s experiment seemed to show that pinyin’s biggest weakness, however – single-character input – might be concealing its greatest strength: the inputting of two, three or more characters at a time.

There was a catch, though. For Zhi’s approach to work on a larger scale, Chinese computers would need to be outfitted with something they had never really needed before: digital Chinese character databases, known in Chinese as Hanziku or ciku.

Zhi’s Quick-Code system contained a few dozen Chinese words, which was clearly not enough. For this strategy to work at scale, Chinese computers were going to require a digital Chinese dictionary containing thousands – even tens and hundreds of thousands – of multi-character Chinese compounds, proper names, place names, technical terms, four-character idiomatic expressions and more.

Without these, there would be no way for a computer to translate keyboard entries such as “A-Q” into 安全 (anquan).

The era of digital Chinese dictionaries began in the mid- to late 80s. Chinese input libraries mushroomed, with a host of institutes, companies, government bureaus and everyday users working to create new ones and expand existing ones.

In 1986, one of the largest digital lexicons was developed by the Beijing Institute for Aeronautics and Astronautics. Meanwhile, a library of more than 100,000 common words and terms from traditional Chinese medicine were preinstalled on certain Chinese operating systems.

Even at this early stage, the scale and scope of such input libraries – and even more so the labour that went into their creation – was staggering.

During the mid- to late 80s, a Chinese doctor by the name of Zhang Guofang spent years combing through a corpus of around 10 million characters, encompassing lower-school and middle-school textbooks, along with other materials.

On this basis, he went on to produce what he referred to as a four-level lexicon or ciku. The first level included a set of 5,633 commonly used character compounds. Levels 2 to 4 – which comprised 96,000 character compounds – drew upon research conducted at Chengde Medical College and People’s University.

Known as the “General Word Set for Chinese Character Keyboard Input”, this 110-page standard included 43,540 entries, divided into three ranks based on frequency. These, and dozens of other short cuts, allowed users to retrieve a set of commonly used compounds specially encoded in computer memory.

Also in the early 90s, three organisations – including the influential Chinese Information Processing Society of China – joined forces to produce the “Compendium of Commonly Used Words for Use in Chinese Character Keyboard Input”.

Chinese engineers had grown so confident with one- and two-character Chinese input that they set out on a new and more ambitious goal: the computational prediction of multi-character passages – even entire sentences.

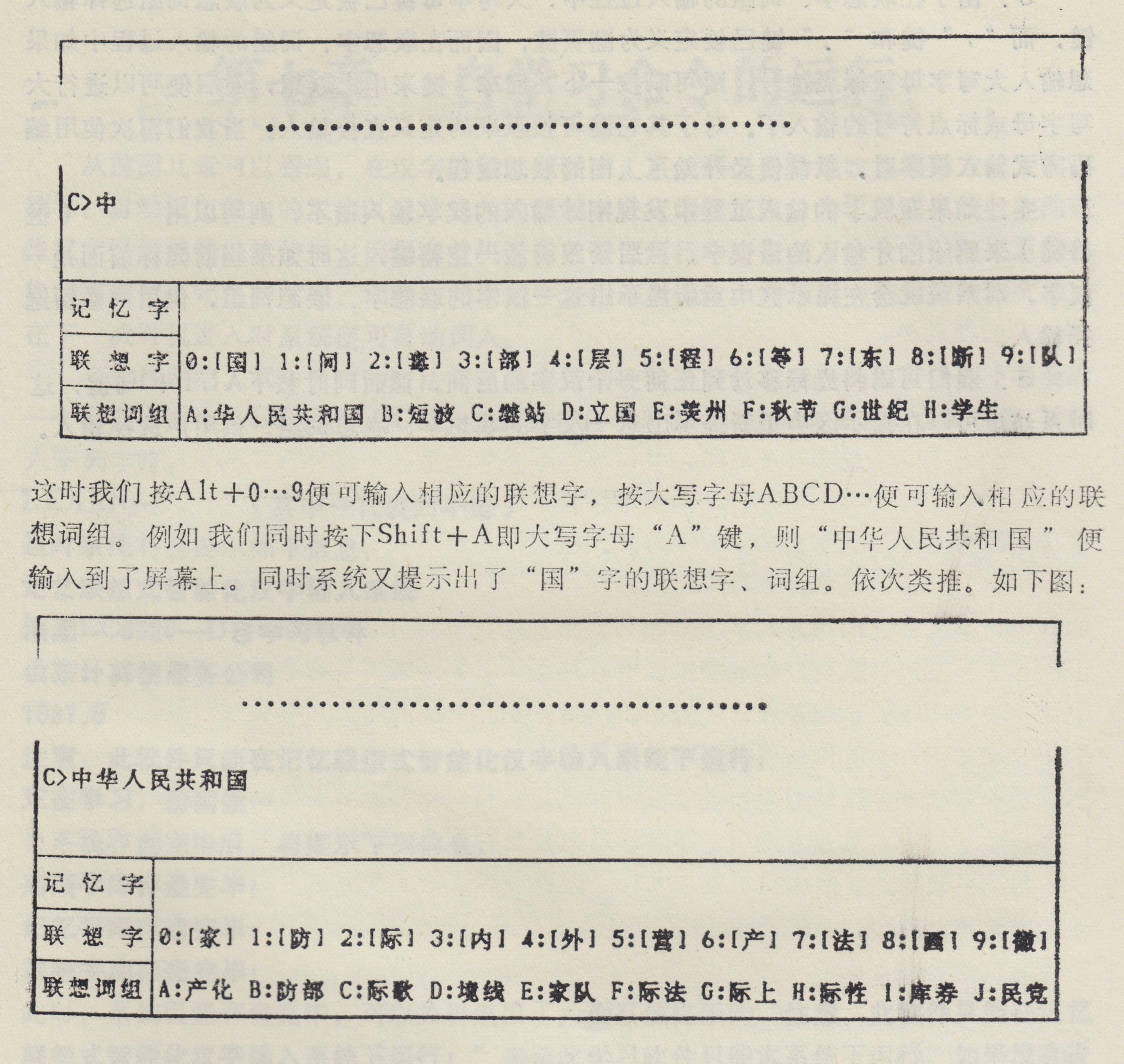

In the early-90s version of the popular Chinese operating system CCDOS, for example – a Sinicised version of DOS – the installation pack came with a floppy disc labelled “Associative Character Compound Library” (lianxiang ciku), or more literally, the “Library of Connected Thoughts”.

Using “connected thought” input, Chinese IMEs no longer limited themselves to guessing which character the user wanted based on his or her keystrokes. Now they would try to guess the next character the user might want, even before he or she depressed another key on the keyboard.

When the user inputted a Chinese character – 联 (lian, “to connect”), for example – the IME would immediately begin trying to work out the next most likely character in the text. These guesses were presented in the pop-up menu, for selection by the user.

In this case, the IME would suggest合 (he), for example, which a user could select to write the two-character word “united” (联合, lianhe); 邦 (bang), leading to “federal” (联邦, lianbang); 络 (luo), leading to “connection” (联络, lianluo), and so forth.

If one of the IME’s guesses proved accurate, the user could select one of these predicted characters without inputting them from scratch. Pinyin input systems were no longer limited to using abbreviations to produce two-character Chinese words, then; now Chinese IMEs were starting to predict a user’s next word, as a way of speeding up the inputting process.

The Library of Connected Thoughts didn’t stop at the next character, however. It kept on guessing.

If the user selected 联 followed by 合, for example, the IME’s next suggestions might include 国 (guo), leading to the three-character Chinese word 联合国 (lianheguo), meaning “United Nations”.

If the user’s selection was 联邦, by comparison, the very next “connected thought” suggestion might be the two-character compounds 德国 (deguo, “Germany”, giving us 联邦德国 or “Federal Republic of Germany”) or 政府 (zhengfu, “government”, giving us 联邦政府 or “federal government”).

“Connected thought” pinyin input became so central to Chinese computing that the term itself was eventually enshrined as the name of one of China’s most influential computing companies ever: Lenovo, the firm that, in 2005, took over IBM’s personal computing business. Lenovo’s Chinese name is Lianxiang, or “Connected thought”.

In the opening decades of the 21st century, engineers took Chinese input text one step further:

Chinese IMEs entered the cloud, enabling predictive text suggestions to harness vast, dynamic, ever-growing, user-generated text corpora to deliver ever-longer and more accurate “connected thought” recommendations to users.

A comparison here might be the Google search bar, which, beginning in the early 2000s, began to make suggestions to the user by analysing their search terms and comparing them against those of millions of other users.

But unlike the Google search bar, cloud input was used in the context of Microsoft Word, email, text messages and browsing the web.

In 2013, Microsoft researchers touted the growing power of its Chinese IME while Sogou boasted far greater accuracy and performance for its cloud-based IME.

“Long sentence accuracy” – the ability for an IME to convert a long and complex sequence of alphabetic letters into an accurate, multi-character Chinese passage – has grown from a reported 62.5 per cent on locally stored IMEs to 84 per cent with cloud input, Sogou reported, while “short sentence accuracy” was reported to grow from 91.52 per cent to 96 per cent.

Cloud input (yun shurufa, 云输入法), simply put, was getting better and better at guessing the user’s next character.

By the 2000s, in fact, developers had pushed Chinese predictive text to a point once considered unimaginable, where Chinese inputting speeds – bolstered with ever more sophisticated predictive text capabilities – began to outstrip those of English, long considered the unsurpassable benchmark of modern human-computer interaction.

Loading up a cloud-based phonetic IME, for example, one can enter the string zhrmghg and watch as it correctly suggests 中华人民共和国 (Zhonghua renmin gongheguo or “the People’s Republic of China”): a mere seven keystrokes, as compared to 26 to type out the entire pinyin spelling.

If one prefers an example from deeper in antiquity, we can return to the line from the Tang dynasty poem that we started with: “I dismount from my horse and offer you wine.”

Chances are good that your Chinese IME – if it is outfitted with cloud-based input functionality – will be able to produce this passage with nothing more than five keystrokes: admittedly, this is one of the best known of all Tang poems, which helps account for why a Chinese input system might have this stanza stored in memory.

At the same time, however, I invite English-speaking readers to try typing the following sequence in Microsoft Word or elsewhere: sicttasdtamlamt.

Was your machine able to identify the comparably famous sonnet by Shakespeare? Chances are slim.