Just 10km (6.2 miles) from the Chinese border, in the most northerly reaches of Gasa district, Laya is accessible only on foot or by helicopter.

When setting out, reassured by the guide that the hike would be a mere 12km, the helicopter option seemed like a ridiculous idea. After completing about a third of the journey, it is not sounding so silly.

The challenge is not so much the walking, which is along a well-marked path that follows a fast-flowing river, crosses wooden bridges and passes white-painted chorten (stupas) containing prayer bells that are kept turning by mountain streams. The biggest hindrance is the altitude.

Altitude sickness affects people differently, but is often felt above 2,500 metres. The most common effects are giddiness, disorientation, headaches and vomiting.

For most visitors to Laya, rest, lots of liquids and a careful husbanding of their energy will enable them to acclimatise quickly. But it can still be galling to see the locals scampering around without a care in the world.

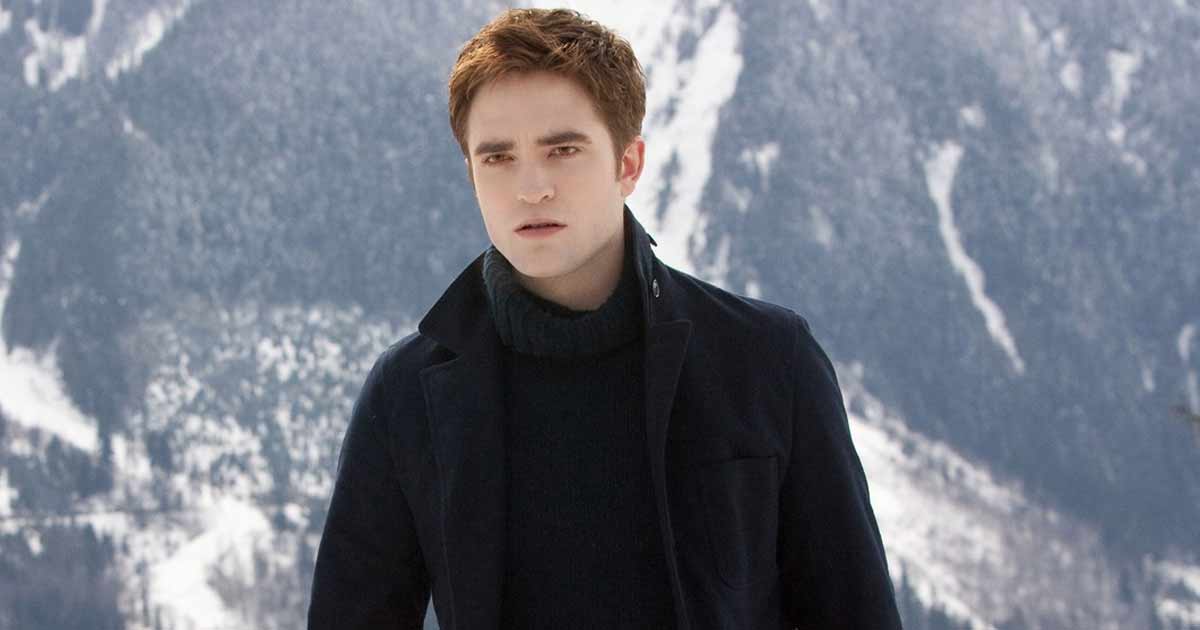

Laya is spread along a south-facing slope that plunges into a tributary of the Puna Tsang Chu river and is overlooked by towering, snow-covered mountains.

A walled school complex stands in the middle of the village, with small shops clustered nearby. Dirt tracks lead between homesteads.

In the two-storey houses, living quarters are up a steep flight of wooden steps, while the lower level is set aside for livestock during the bitter winter months.

Eaves and exposed woodwork are decorated with colourful designs. Stylised renderings of dragons, tigers, mythical flying horses and ravens on the exterior walls ward off bad spirits.

The first Royal Highland Festival took place in October 2016, to mark the birth of Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck, the first son and heir of the king of Bhutan. The date was also the 400th anniversary of the start of the reign of the great lama Zhabdrung Rinpoche, the founder of the Bhutanese state.

King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck has supported the festival from the beginning and visits each year, always opting to trek to the village and mix with his people.

This time (October 2023), he is with his eldest son, while the queen has remained in Thimphu, having recently given birth to a daughter.

Along one side of the festival ground is a line of hexagonal black tents, the king’s pitched in the middle, behind a flagpole bearing the kingdom’s flag, complete with the druk, or thunder dragon.

The tents are intended to give protection from the wind, not for staying the night in. Individual visitors have been assigned to homestays while larger groups are housed in the school, temple halls and other communal buildings.

Hundreds of visitors stand in a wide semicircle on the far side of the field: contestants from other highland villages, and Layap people, the men wearing traditional knee-length gho in red and orange, the women in black woollen jackets that reach down to their ankles, and conical hats of woven bamboo that are held in place with strings of brightly coloured beads.

The opening ceremony commences with a parade of musicians, dancers, religious leaders and herders leading yaks and horses into the centre of the field.

Young monks in saffron robes struggle under the weight of two-metre-long dungchen horns, while colleagues keep up a continuous, reverberating note.

Others keep time with gongs or carry prayer flags in the traditional blue, white, red, green and yellow that connect positive energy and spirituality.

At around 9am, the king stands with his son in front of their tent to address the crowd. He is introduced by the master of ceremonies, who reads out a short statement on the king’s behalf. The festivities may now begin.

The people of Laya perform the first dance, their colourful costumes shimmering in the thin air. Another performance, the yak dance, is delivered by members of another village in honour of creatures that are critical to the well-being of highland communities, providing everything from milk and meat to wool for their clothes.

The rivalry seems friendly as a series of competitions between villages begins. The saddling contest tests how long it takes a rider to prepare one of their sturdy, short-legged ponies and is followed by a race across the hillside to a distant flag and back.

One rider tumbles at the very start and is still attempting to catch his horse as the others return to the finishing line.

After a fashion parade of men and women in traditional highland fabrics, powerfully built fighters take their turn within a rope ring, grappling to be crowned the strongest in a sport that resembles Mongolian wrestling.

Trials of strength for women involve throwing heavy sacks over their shoulders and running the length of the field.

Elsewhere, judging is taking place in the most-attractive-yak competition, contestants decked out in colourful saddles with tassels, headdresses and ornaments dangling from their horns.

Yaks are remarkably docile and these beauties are content to ruminate on the wiry grass as the hubbub goes on around them and the judges assess their relative merits.

The winners will turn out to be a stunning pair with long hair that is dark across their shoulders but fades to near white as it hangs from their bellies.

The judging is interrupted by a deep horn signalling that the runners of the 22km race from the town of Gasa are approaching the finishing line.

Astonishingly, the winner completed the course in a couple of hours – it took me twice as long to hike half the distance yesterday.

Still struggling with the altitude, I survive on water and a few handfuls of rice but an area to one side of the festival site has been laid out with a dozen or more stalls selling rice dishes, pasta and thick soups.

Around the outside of the field are other stalls, selling clothing and slippers, cheese and milk, all of which comes from yaks.

Day two of the festival will feature more music and dancing, a three-legged race, a pillow fight and, finally, a tug of war to determine the strongest village. But as the sun goes down on the first day, the courtyard of the village school fills with villagers and visitors, bonfires keeping the chill at bay.

On the steps of the school, a series of Bhutanese pop stars, dancers and traditional musicians perform well into the night.

As the crowd applauds and sings along, the king walks easily among them. They smile and dip their heads, but no one attempts to take a photo – a major no-no in Bhutan – or to strike up a conversation, although they do speak with him when he breaks the ice.

Watched carefully by two minders, one with a pistol nestled on his hip, the young prince is warming himself by one of the courtyard’s fires. On the other side, two slightly grubby boys of around the same age watch him carefully.

Even at this age they understand the protocol, but ever so slowly, they inch closer. Eventually, they are alongside the prince. He smiles and holds his palms out to warm them on the fire. They shyly return his smile and copy his movements.

Respect goes both ways in Bhutan.

This year’s Royal Highland Festival will take place on October 23 and 24.