But the Tokugawas need not have worried; the Maedas wanted to secure their region’s future by investing in crafts rather than weaponry.

Doing so not only transformed Kanazawa into one of Japan’s most prosperous cities (even today, 99 per cent of Japan’s gold leaf is produced here), but also afforded a certain amount of protection because of the presence of the finest artisans, literary scholars and tea ceremony masters.

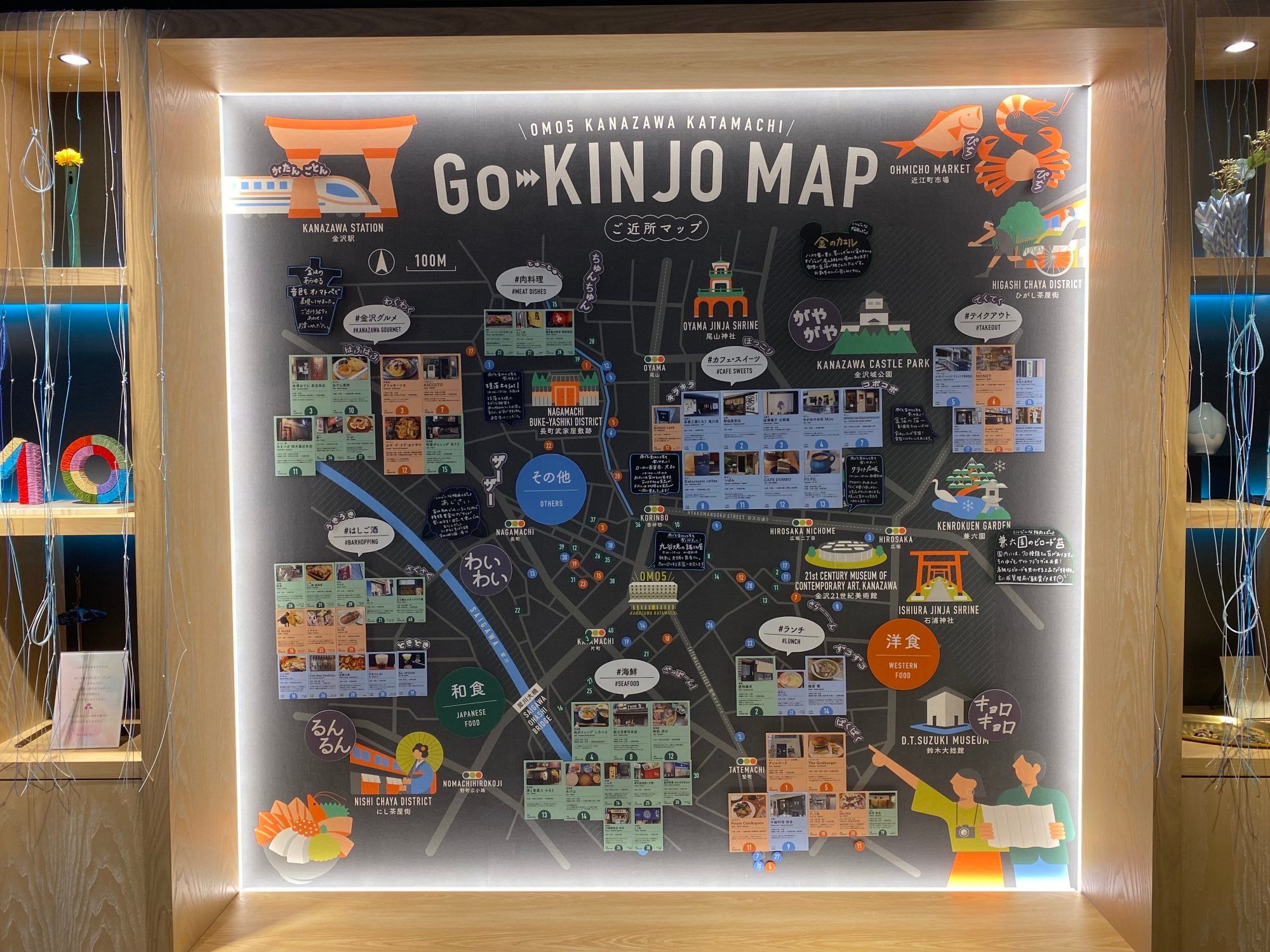

Open to visitors to Kanazawa’s Nagamachi neighbourhood, otherwise known as the Samurai District, are well-preserved Edo-era homes, many of which have a room dedicated to tea ceremonies.

This is where rivals met to thrash out disagreements, and features such as low doorways – which, according to my guide, forced visitors to bend forward as if bowing – reminded warring parties that nobody was inferior to anyone else.

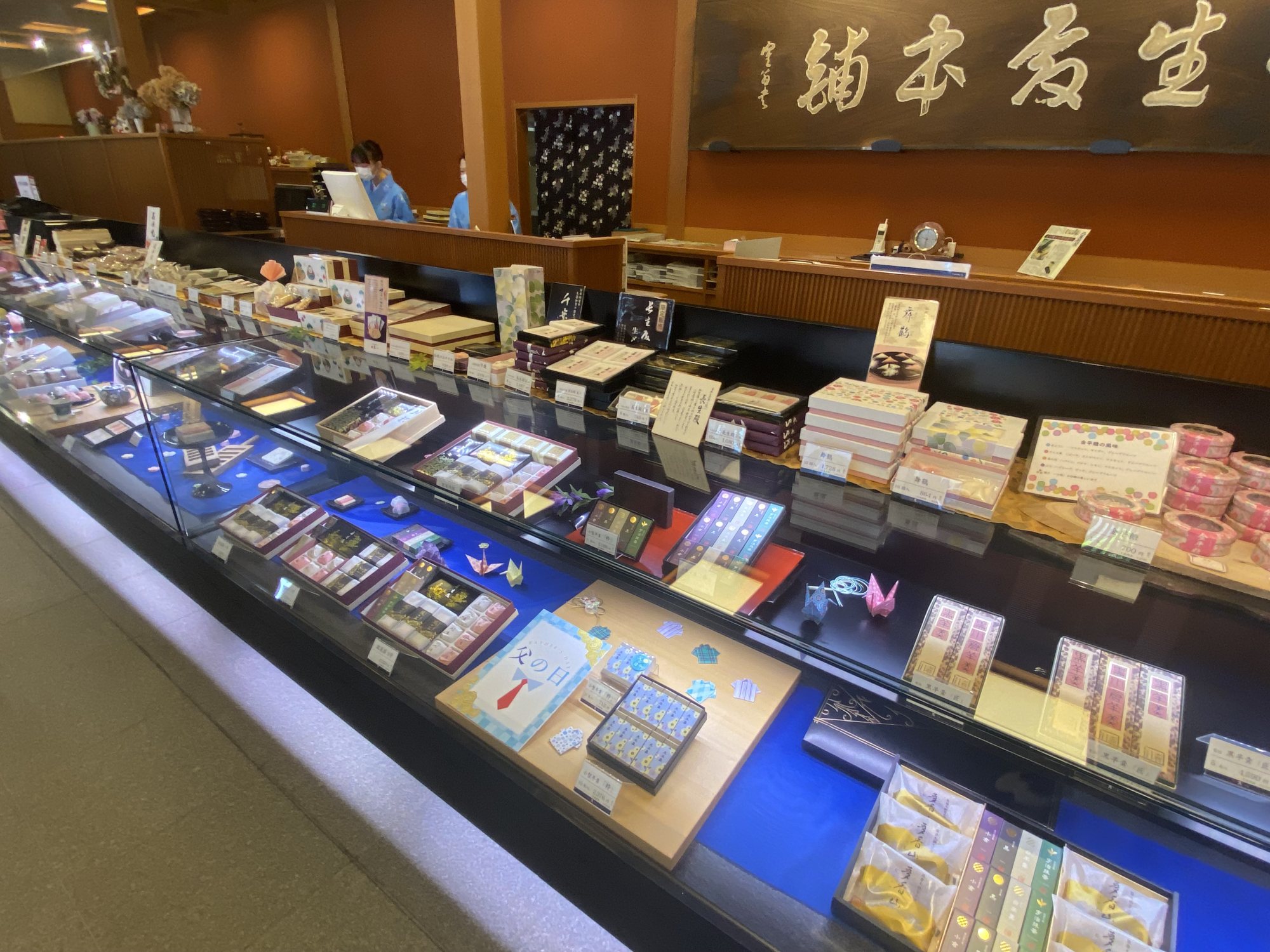

Mouthwatering displays of beautiful confectionery – including chouseiden, tablets of pressed sugar adorned with intricate images – of the type served during these ceremonies are on display at Morihachi, a confectioner dating back to 1625.

A kimono-clad employee shows me the store’s museum – a room lined with hundreds of wooden sweet moulds, some dating back to the 1600s. Many bear ornate flower designs (plum blossoms, the Maeda clan’s trademark, feature heavily) while others depict long-legged cranes, a symbol of longevity.

Elsewhere, the support of traditional crafts is the raison d’être of the Kanazawa Utatsuyama Kogei Kobo. Funded by the city, the aim of the centre, which opened in 1989, is to promote, preserve and protect the five key Kanazawan disciplines: urushi (lacquerware), dyeing, ceramics, metalwork and glass blowing.

The centre takes in students who wish to learn – and thus preserve – the ancient arts, and director Nobuhisa Kawamoto takes me downstairs, to a maze of studios, to meet some.

In one room, a student uses a pole to retrieve a glowing orb of molten glass from a kiln. Next door, a student sitting cross-legged on tatami matting bends a thin strip of metal into a circle, his armoury of tools laid out on tree trunks repurposed into workbenches.

The Kanazawa Utatsuyama Kogei Kobo receives applications from all over Asia and accepts a maximum of 31 students per intake. Students (who make their own tools) study for either two or three years, and must already be proficient in their chosen discipline.

Some students have reinvented crafts in ways that revive their appeal.

The work of one of the centre’s alumni, Terumasa Ikeda, who cites his inspirations as manga and video games, is on display at Kanazawa’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art.

For his Error-Brick artwork, Ikeda, who uses modern techniques such as pulse lasering alongside traditional urushi methods, adorned a chunk of jet black rock with lacquer and tiny, emoji-like symbols made from mother-of-pearl.

The passion for crafts permeates all aspects of life in Kanazawa, and meals are no exception.

Lunch at Coil, a sleek sushi restaurant with all-white decor that brings to mind a spaceship’s interior, is defined by the way in which the sushi is served.

After I select ingredients from a menu listing everything from horsemeat sashimi to paprika pickles, a wooden box is placed on my table. Beneath the tatami cover are four shelves containing layers of rice-topped seaweed, ready for me to top with my chosen ingredients and roll into place.

In the restaurant’s tea bar, neat rows of brass jars are laid out next to tiny teaspoons forged from hammered metal. I opt for a local tea made with roasted rice and take my ceramic teapot over to a counter, using an ornate wooden ladle to pour hot water onto the leaves.

At Crafeat, a tiny, izakaya-style restaurant in Kiguramachi, an area of Kanazawa filled with cosy independent restaurants, the bite-sized dishes pay homage to local artisans past and present.

A delicious dashi soup, for example, is served in a lacquerware bowl, while my ramen come in a Kutani porcelain dish. To unroll my napkin, I must untangle a knot of mizuhiki (stringwork) – coloured threads made from paper and another Kanazawa speciality. Somehow, I do so without breaking the delicate rainbow-hued threads.

The weird and wonderful trinkets on offer at gallery-cum-store Wai include brass key rings shaped like helmets worn by the Maeda clan, but with a twist – the tapered helmets double as screwdrivers.

Wai is also reducing the waste usually associated with making Kutani porcelain. Items with even minor imperfections tend to be destroyed, but here they are transformed into quirky plant pots.

Visitors can watch workers slice sections of gold leaf using delicate bamboo tools, all while holding their breath (the gold is so thin that simply waving my hand over a piece floats it into the air), or sign up for workshops.

I choose one that involves adorning chopsticks with gold leaf, and discover that that is an activity best left to the experts.