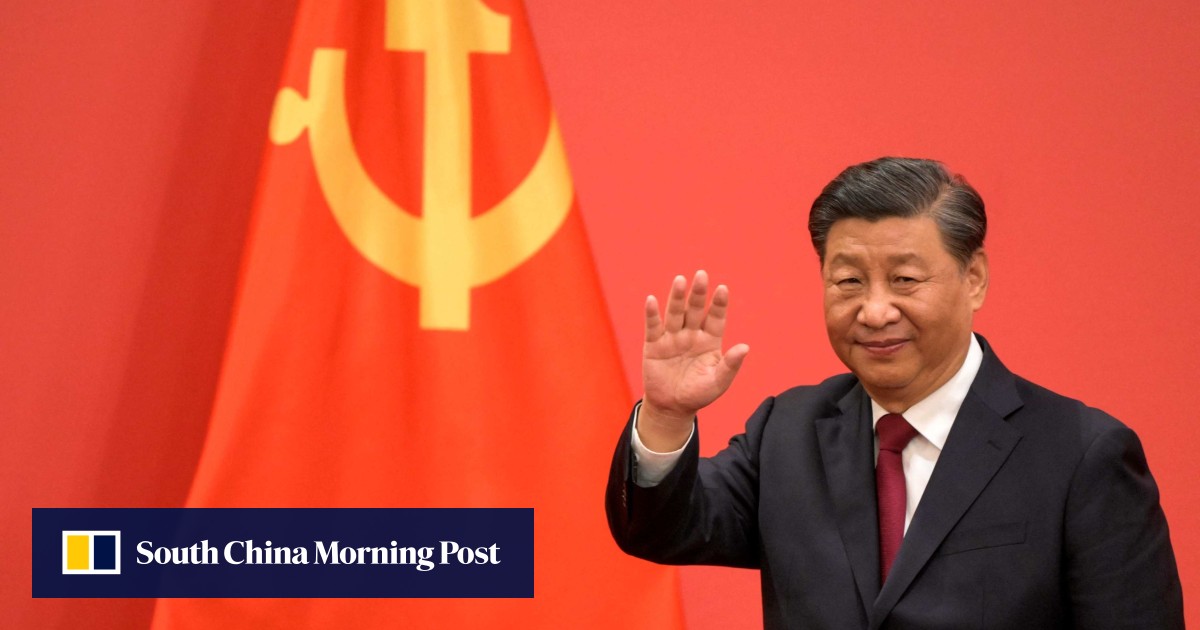

The databank includes a relationship network to show how each of the seven top political leaders is connected to the party’s 20th Central Committee – the pool from which they were drawn. It also shows where they crossed paths based on their official work history.

Collectively, the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, including Xi, have more links with the 376 full and alternate members of the decision-making Central Committee than previously – a clear indicator of the concentration of power within the party.

But direct associations with Xi – widely regarded as the most powerful Chinese leader in decades – have dropped in percentage terms from five years ago.

The Post tally shows 49 new Central Committee members have direct links with Xi through either work or education, making up 22 per cent of the total connections with Politburo Standing Committee members. That is down from 32 per cent in 2018, when Xi had 42 direct links.

Xi does, however, retain the widest network of direct connections of all the Politburo Standing Committee members.

China’s leaders prioritise economic stability and investor confidence for 2024

China’s leaders prioritise economic stability and investor confidence for 2024

His percentage fall is due to an overall expansion in direct links – the seven Politburo Standing Committee members are now directly associated with 226 of the 376 Central Committee members – up from 131 five years ago, a jump of more than 70 per cent.

The Central Committee is the nerve centre of Chinese politics and its decisions chart the course for the country and the party’s 98 million members.

Zhao Leji, who heads the legislature, and Wang Huning, the party’s ideology chief, were on the previous Politburo Standing Committee and have stayed on for another five-year term. Their personal networks within the Central Committee have seen moderate growth from five years ago – Zhao’s direct links went from 12 to 21, while Wang’s have increased from seven to 15.

This means that while Xi now commands more support from the Politburo Standing Committee, his personal bonds with the Central Committee members are less direct than before. He is relying more on his deputies to build rapport with those in power at the lower level.

One reason for this is that many of the political elites known to Xi personally are reaching or have passed the official retirement age, according to a Peking University researcher.

“Xi has selectively extended the retirement age for some key positions, such as for Taiwan affairs chief Song Tao, and Hong Kong and Macau affairs chief Xia Baolong. But these are exceptions, and they did have to step down from the Central Committee,” said the political scientist, who declined to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter.

“It is not surprising that Xi has increasingly relied on his most trusted and younger allies to recommend people to fill the key positions.”

Premier Li Qiang, for instance, has direct links with 39 people on the Central Committee or above, including Xi and fellow Politburo Standing Committee member Cai. Most of those connections are from Li Qiang’s time in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces and Shanghai, from the 1980s to 2022.

That makes him better connected at the top than his predecessor Li Keqiang, who died suddenly in October. Li Keqiang had direct links with 24 members of the previous Central Committee.

Cai, Xi’s chief of staff, has 42 direct connections, while disciplinary chief Li Xi has 46, making him the second-best connected Politburo Standing Committee member after Xi.

“Li Qiang, Cai Qi and Li Xi had all been transferred to many regional jobs before being promoted to the Politburo Standing Committee, so it’s natural that more Central Committee members have crossed paths with them,” the researcher said.

Li Qiang’s roles include a stint as chief of staff to Xi when he was the party boss of Zhejiang province nearly two decades ago. Li Qiang was promoted to governor of Zhejiang soon after Xi became the top party leader in 2012, and he went on to become party secretary of Jiangsu, followed by Shanghai.

Cai has also served under Xi in regional and government roles in Fujian, Zhejiang and Beijing.

Li Xi – who is from Liangdang county in Gansu, where Xi’s father Xi Zhongxun launched a communist uprising in 1932 – worked in the province before he was transferred to Xi’s home province of Shaanxi. He went on to leadership roles in Shanghai, and in Liaoning and Guangdong provinces.

Ding has spent most of his career in Shanghai, including as Xi’s top aide before he became head of the General Office of the party’s Central Committee.

John P. Burns, an emeritus professor of politics at the University of Hong Kong, said despite the dominant presence of people associated with Xi on the Central Committee, politics within China’s top echelon was “dynamic”.

“Even though Xi has installed his own people [at the top] each of them brought their own subordinates with career ambitions. This is what gives politics at the top a level of instability.”